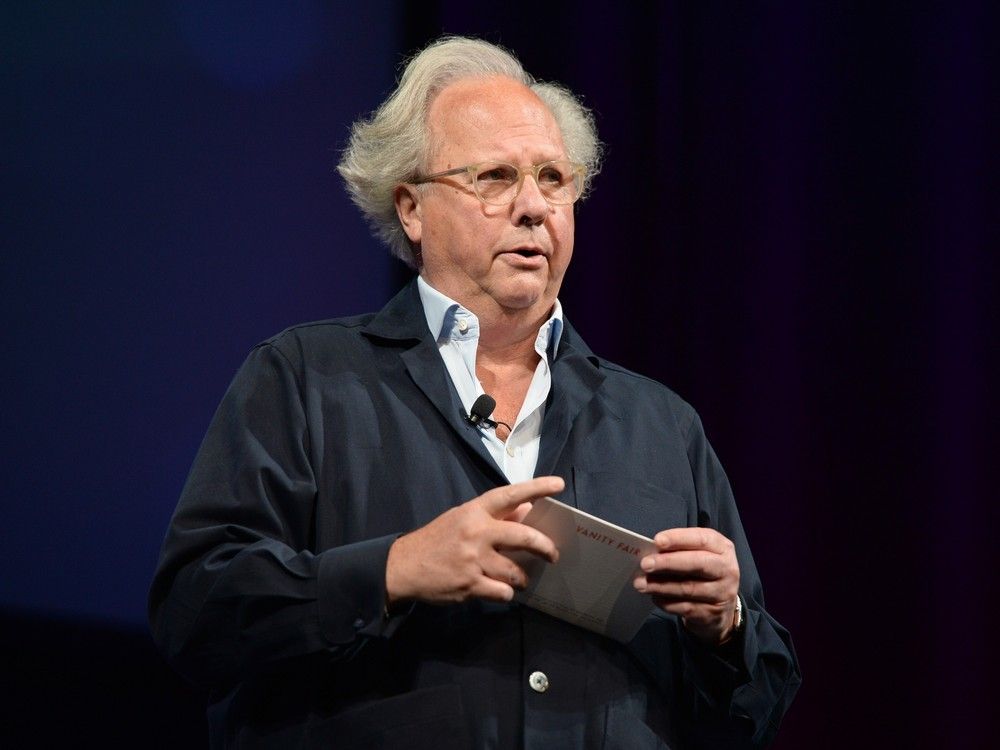

One of the most celebrated magazine editors of his generation, Graydon Carter grew up in Ottawa an unlikely success.

His altogether miraculous rise from university dropout — he was a distracted student at both uOttawa and Carleton — to the editor’s chair at Vanity Fair during the golden age of magazines is chronicled in his new memoir, “When The Going Was Good.”

Carter, now 75 and the eminence grise of New York City style, spent his formative years in Manor Park, where he was a resentful victim of Ottawa’s winter, much burdened by its wools and flannels.

The book reveals he was so directionless as a young man that he fell into the federal bureaucracy — and narrowly escaped a career as a public servant.

“I had dreams, but nobody would have ever called me ambitious,” writes Carter. “It could also be said that my parents, and indeed a good number of my friends, thought that life, in the professional sense, had little in store for me.”

Carter’s Saskatchewan-born father, Edward, was a Royal Canadian Air Force pilot and Second World War veteran who loved nothing more than to fart and to collect wood. He won the heart of Graydon’s mother, by among other things, farting loudly in a crowded movie theatre and blaming her for the crime, and he boasted to friends of his ability to bum trumpet the theme song from “The Bridge On The River Kwai.”

Carter remembers being press-ganged to poach firewood from the Greenbelt. His father was “a bit tight,” Carter reports, and would regularly enlist him and his brother to help troll National Capital Commission forest in search of felled logs.

“Like moonshiners,” he writes, “we did all this in the near dark, with just the jerky movements of my father’s spotlight casting an eerie silent-movie aspect to the agony.”

Carter’s mother, Margaret Kelk, was considerably more refined. The daughter of a soap executive, she grew up in Toronto’s Forest Hill neighbourhood, attended Havergal College, and summered at the family’s Muskoka cottage. She was dating the captain of the University of Toronto football team when Edward Carter suddenly blew into her life.

They married in September 1946, and welcomed their first son, Graydon, three years later. In the early 1950s, the family moved to Zweibrücken, Germany, where Edward Carter was stationed with the RCAF.

Upon their return to Canada, the family settled in Ottawa’s Manor Park. Graydon was then seven years old and unhappy to find himself in what he perceived as a frozen wasteland.

At the time in Ottawa, Carter writes, “hockey was everything in part because there wasn’t much of anything else.”

Their lives revolved around hockey and downhill skiing in the winter, and canoeing, fishing and street hockey in the summer.

“Ottawa itself was a quiet, post-Edwardian capital of moody stone-and-brick government buildings,” Carter writes. “The main department store, Ogilvy’s, sold thick clothing, and almost all of it was in tartan. There were few restaurants, and when a pizza parlour opened, the news of its arrival made the local paper.”

Children rode bikes everywhere, roamed their neighbourhoods all day, and exercised near total freedom. “Like many parents of their generation,” Carter says, “mine were benign and largely absent.”

He struggled in school. An avid reader and constant daydreamer, Carter pursued his own interests rather than what was on offer in the classroom. He struggled, too, to follow oral lessons, which he heard as “random words.” “I can only describe it as a form of oral dyslexia,” he writes of the condition. “In order to absorb anything, I have to read it.”

Carter enjoyed Saturday matinees at the Elgin and Capitol theatres, swimming at the Chateau Laurier pool, music at Le Hibou Coffee House on Sussex Drive, and watching The Phil Silvers Show on TV. (Silvers played Sgt. Ernie Bilko, a scheming motor pool boss, whom Carter adopted as his management polestar.)

With his mother’s encouragement, he took up painting and drawing. He yearned for a life in New York City’s arts world like the protagonists from two of his favourite books, “

Act One

” and “

Youngblood Hawke

.”

“I wanted to become something, but I had no idea what to become or how to become it,” he writes.

He spent six months working on the prairies as a lineman for Canadian National Railway, and looked for work upon his return to Ottawa.

“I had no marketable skills and so was quickly scooped up by the Canadian government,” Carter writes.

He was identified as management material and assigned to work as a consultant in what was then the Department of Supply and Services. The department was already populated by Peat Marwick consultants, and with nothing to do, Carter read books and newspapers, and invented an efficiency expert, Winston Purdy, who became an office legend.

Finally, in a move that presaged the

Phoenix pay fiasco

, Carter was handed a weighty assignment: to research and write a report on the computer system that managed payments for federal employees, pensioners and veterans. What came to be known as “the Carter report” ran to several hundred pages and explained how the pay system could be improved.

“I left shortly after the assignment was completed,” Carter writes, “and sometimes I lay awake at night wondering if I had made a mistake that would mean government employees or aging veterans wouldn’t get their checks at all.”

Carter turned his back on the public service to pursue a career as an architect, but “hopeless” at math and engineering, he left after one year to study political science at the University of Ottawa.

“I had an interest in political science but no particular passion for making it a career,” he says.

His career drift ultimately came to a halt in uOttawa’s liberal arts building. Passing an open office door, Carter saw a room filled with desks, typewriters and young people: He stopped to ask what it was all about and learned the small group planned to launch a literary and poetry magazine, The Canadian Review.

Carter volunteered his services and was told they could use an art director.

“I told them I could draw, and so the job was mine,” he writes.

Carter had strong ideas about magazines, and modelled the design of The Canadian Review after Scribner’s Magazine, a personal favourite. He threw himself into the enterprise, all but abandoning his classes, and took over as editor within a year’s time.

In the late 70s, he transferred to Carleton University and sought admission to its well-regarded journalism program, but was rejected because of his poor grades. He remained focused on The Canadian Review, not academics, and Carleton administrators eventually told him he couldn’t graduate given his sizable collection of “incompletes.”

As a result, Carter calls himself a university “discard” rather than a dropout. (His unfinished degree would have some strange, unforeseen consequences. When he was editor of Spy magazine, rival New York Magazine exposed him for lying about holding a Carleton arts degree. Later, when he was Vanity Fair editor, Carter had to call Carleton’s School of Journalism, which wanted to feature him in a gallery of successful alumni, to tell them he had been summarily rejected by the school.)

Even though Carter somehow managed to build The Canadian Review’s circulation to a robust 50,000, it ran out of money and closed its doors after four years.

Again at loose ends, but with magazines now in his blood, he applied to a publishing program at Sarah Lawrence College, near New York City. Guest lecturers included editors from Harper’s, Time, Saturday Review, and other leading magazines.

Carter wrote to all of them and asked for job interviews. In the early summer of 1978, he travelled to New York City, and met with one rejection after another. His final interview was with Ray Cave, editor of Time magazine.

Cave suggested there might be something for him in six months’ time, but a desperate Carter prevailed upon him, saying he needed “a job now,” and pressed his hand on the surprised editor’s arm.

The gambit worked: Carter started his New York City odyssey one week later as a writer for Time. He was 29 years old.

In Manhattan, Carter found his spiritual and professional home. After five years at Time, he became a staff writer at Life magazine, then launched the satirical magazine, Spy, with former Time colleague Kurt Andersen in 1986.

Irreverent and snarky, carefully reported and sharply written, Spy captured the city’s 1980s zeitgeist and became a critical success. Its circulation surged to 150,000, but its finances remained precarious. After the magazine sold in 1990, Carter left to take over the New York Observer, a sedate broadsheet that covered the Upper East Side. He managed to turn that, too, into required reading.

All of it brought him to the attention of Si Newhouse, chairman of the media conglomerate Condé Nast, who offered Carter the editorship of Vanity Fair in July 1992. It was one of the richest, most coveted posts in all of journalism, and Carter would hold it for the next quarter century.

His award-winning tenure at Vanity Fair made him a New York institution: rich, famous, Hollywood-connected, an enduring oracle of taste and style. He left the magazine in 2017 as print media suffered in the face of the internet’s relentless advance on all fronts.

“You only realize it was a golden age when it’s gone,” writes Carter, who was invested into the Order of Canada for his contributions to popular culture and current affairs.

He regards his time in Ottawa as critical to his success since the city was home to so many of his failures.

“As I regularly tell my kids, few people learn from success,” he writes. “A worthwhile professional life is built over a boneyard of failure. Early failures, as opposed to successes, are instructive.”

Our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark our homepage and sign up for our newsletters so we can keep you informed.

Related

- Nazi collaborator’s name initially engraved on the Victims of Communism memorial

- Cervical cancer rates rising in Canada, but other countries are close to eliminating it