The royal charter that formed Hudson’s Bay about 355 years ago could soon be getting a new home.

The Canadian Museum of History announced Wednesday that the Weston family, of Loblaw Cos. Ltd. fame, wants to buy the document and donate it to the Quebec institution.

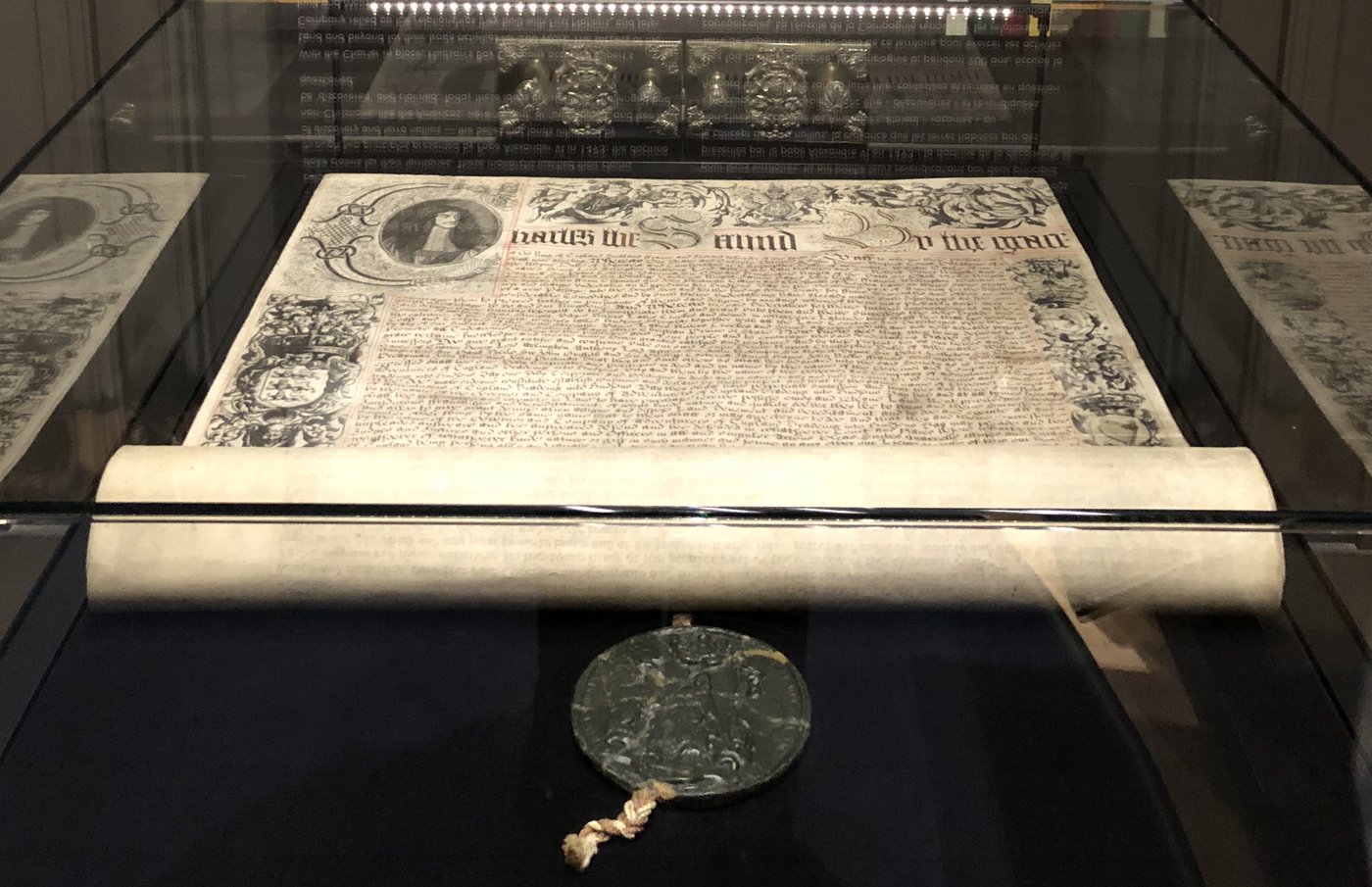

The charter was signed by King Charles II in 1670. It gave the Bay rights to a vast swath of land spanning most of Canada and extraordinary power over trade and Indigenous relations for decades more.

The museum says the acquisition still needs court approval but if that is obtained, the Westons will donate the document immediately and permanently.

“At a time when Canada is navigating profound challenges and seeking renewed unity, it is more important than ever that we hold fast to the symbols and stories that define us as a nation,” said Galen Weston in a statement.

“The Royal Charter is an important artifact within Canada’s complex history. Our goal is to ensure it is preserved with care, shared with integrity, and made accessible to all Canadians, especially those whose histories are deeply intertwined with its legacy.”

His family made its fortune through Canadian retail chains including Holt Renfrew, as well as several European department stores.

As part of its proposed purchase of the charter, the museum said the family has offered additional funding to support “a meaningful consultation process” with Indigenous Peoples on how the Royal Charter “can be shared, interpreted and contextualized in a manner that respects Indigenous perspectives and historical experiences.”

The funding will help the museum explore ways to share the charter with other museums and through public exhibitions.

Caroline Dromaguet, the museum’s president and CEO, said the donation is of “enormous importance to Canada” and “will serve as a catalyst for national dialogue, education and reconciliation for generations to come.”

The Westons expressed an interest in buying the charter after the Bay filed for creditor protection in March under the weight of $1.1 billion in debt.

The company later liquidated and closed all 96 stores under the Bay and Saks Canada banners. It got permission from a judge in April to work with auction house Heffel Gallery to sell 2,700 artifacts and 1,700 art pieces the retailer owned, including the charter.

The move sparked concern from archival institutions, governments and Indigenous groups, including the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, which all worried it would allow pieces of Canadian and Indigenous history to wind up in private hands and away from public view.

Hudson’s Bay hasn’t held its auction nor released a full catalogue of items that will be available, though it has allowed groups to view an inventory of the collection if they sign non-disclosure agreements.

A source familiar with the Bay’s collection, who was not authorized to speak publicly, told The Canadian Press previously that paintings, point blankets, paper documents and even collectible Barbie dolls are part of the trove.

Historians believe the charter is likely the most coveted piece the retailer owned.

“It’s 100 per cent their crown jewel,” said Cody Groat, a historian of Canadian and Indigenous history who serves as the chair of the UNESCO Memory of the World Advisory Committee in an April interview.

“There is no doubt this is the most significant document that the Hudson’s Bay Company has access to or that they’ve ever produced.”

Thomas Caldwell, CEO of Toronto investment manager Urbana Corp., agreed. He told The Canadian Press in the spring that he was interested in purchasing and giving the parchment document with a royal wax seal to a museum.

At the time, he said donating the piece would “make more sense” for whoever buys it because “it’s a big hassle to have something historic like that in an office or in a home.” He speculated that it would need to be insured, have constant security and likely require storage in precise temperatures to preserve it.

For many years, the Bay kept the royal charter at its head office in Toronto, though it was temporarily loaned to the Manitoba Museum in 2020.

That museum and the Archives of Manitoba hold the bulk of the Bay’s artifacts. The company donated them to the organizations in the 1990s, so many thought they’d be a natural home for the charter.

“We know exactly where it belongs in our system,” Kathleen Epp, keeper of Manitoba’s Hudson’s Bay Co. archives, told The Canadian Press in April.

“We think of (the charter) as part of our records in a way already because … we’ve got the rest of the story and so we feel like it makes sense for the charter to be here and to be as publicly accessible as any of the other records.”