Images of an angel and a devil inked onto the left arm of Glenn Kulka are a lens into

the battle

that’s

long raged

within the former Canadian Football League player.

Good vs. bad. It’s always been a fine line, a moral conundrum, an inner donnybrook

between light and darkness

.

“It’s a battle for me,” Kulka said. “I’ve still got the devil in the other pocket.”

In Glenn Kulka’s life, there have been big wins and big losses. There have been struggles with addiction and steroid abuse, with at times unbearable pain and headaches leaving his beaten-down body unable to fully function.

There’s also been a reckoning, a discovery of faith and the ability to lean on a belief in God and Jesus Christ. With that, there is serenity where there was once a raging fire within Kulka’s big-boy 6-foot-3, 280-pound body.

As an athlete, Kulka, now 61, had so much success to celebrate. On top of his football career, he competed in the WWF (now WWE) for a short time, then fought in mixed martial arts.

It would be easy for Kulka to look in the rear-view mirror, wonder about the whys and the what-ifs. It’s just not productive. All the years of contact sports and abuse to his body have left him with brain damage.

“Thirty-five years of cocaine addiction, 35 years of marijuana addiction, 35 years of alcohol addiction … I don’t spend much time dwelling on it these days,” Kulka said. “I’m ashamed of some of the things I’ve done, some of them I can’t talk about.

“Honestly, I think I would have been in the NFL if I had my shit together. But there are certain rabbit holes I just don’t go down anymore.”

Kulka is well spoken and honest, brutally honest, about his rollercoaster ride of a life journey.

“Everybody has their own poop,” he said. “How you deal with that shit is what defines you as a person.”

At 13, Kulka was sneaking shots of whisky, vodka and Drambuie from his parents’ liquor cabinet.

It was a springboard to drugs. The highs masked his insecurity.

In 1992, while he was playing for the Ottawa Rough Riders, he was busted for possession of cocaine. One-point-five grams of it was found in his loaner car late one night in front of a strip club.

“When all the lights went out, after I was done playing football, I would drink a 26er of vodka,” Kulka said. “It’s a daily grind. You’re an addict and alcoholic for the rest of your life.”

He doesn’t know what tomorrow brings, but he knows he can make a difference today. There’s a thirst to help others in a world that took big bites out of him along the way. He’s become involved with S.O.S. Steps off the Street, a group of volunteers, led by Gerald Jorgensen, who are helping those who are homeless, addicted, or both. Steps off the Street has become a beacon of hope for people whose lives have bottomed out.

IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WAS SPORTS

To understand what makes Kulka tick, we have to turn back the clock … a lot.

Kulka, a defenceman, played in the Western Hockey League from 1981-83.

He turned to football and joined the Bakersfield College Renegades from 1984 to 85.

At 19, he had ‘Gotta Win’ tattooed on his right shoulder. He lived by the code.

“When you’re an athlete at that level, it’s all about getting a job done,” Kulka said. “Nothing else matters. I looked in the mirror one day and thought to myself, ‘It doesn’t matter how you do it, just do it, you have to win all the time.’ So, I thought, ‘I’m going to get that tattooed on my arm.’ ”

Kulka played in the CFL from 1986-95 with Edmonton, Montreal, Toronto, Saskatchewan and Ottawa, producing 48 sacks and 215 tackles.

“I was going to be an athlete, that was what I thought about from an early age,” Kulka said. “It was going to be sports, it was just a matter of which one. I happened to pick the one that paid less than five-pin bowling on TSN.”

A defensive lineman, Kulka was told he needed to gain 15 pounds before he stepped onto a CFL field. He turned to steroids, injecting them into his thighs, shoulders, triceps and butt cheeks.

“Nobody cares how you get results,” Kulka told Postmedia a few years ago. “It doesn’t matter how you do it or how you get there. I had to be as big, fast and strong as I could be.

“A friend offered me Dianabol, he said it would make me stronger. I broke it in half and I had multivitamins wrapped around it. It was like a Fred Flintstone chewable. There was no league policy against any kind of performance-enhancing drugs. I had to keep up with the Joneses.

“It doesn’t make a bad athlete good, but it can make a good athlete great. You are morally trying to check yourself. But you’d see the results and it wasn’t a problem after that.”

In 1994, he returned to the ice, with two goals and an assist in nine games with the Hampton Roads Admirals of the East Coast Hockey League (coached by John Brophy).

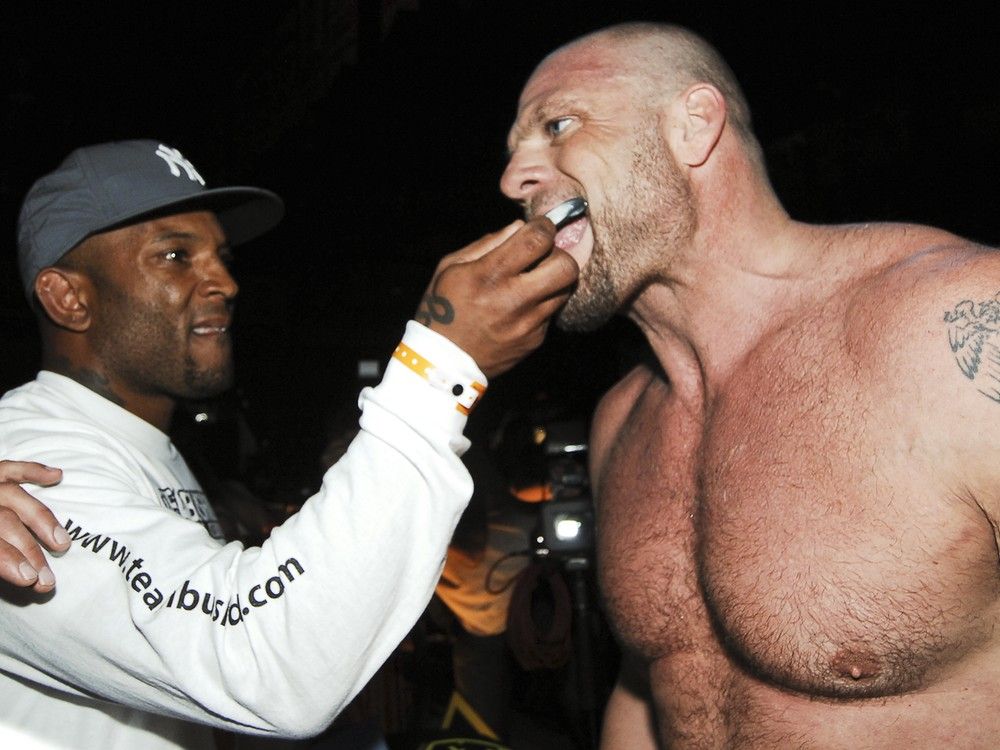

After joining WWE (then the WWF) in the late 1990s, training with Bret Hart, Kulka blew out his knee and was released in 2000.

“They were putting a wellness policy into place and they were trying to weed out the bad guys,” Kulka said.

At age 44, he became an MMA fighter, competing in three bouts

ROCK BOTTOM AND BEING SAVED BY A DOG

When the calendar turned to 2000, Kulka was in trouble.

“I was taking every drug you can imagine … cat tranquillizers, cocaine, ecstasy … I was a full-blown alcoholic and addict, Kulka said. “I was way beyond trying to figure out why it was going on.

“I can remember at one point, my accountant looked at me and $13,000 or $14,000 was unaccounted for. I knew where it had gone.”

Around midnight one night back in April of 2000, drugged and boozed up with a 16-gauge shotgun in hand, Kulka took his purebred black Labrador retriever Rocco and walked a kilometre from an apartment in Ottawa’s east end to a park near Petrie Island.

“I had been drinking, snorting and smoking. This was rock bottom,” Kulka said. “I had every intention of taking my life. I put the gun in my mouth. But then I thought, ‘I can’t leave Rocco here.

He’ll get lost and won’t find his way home.’ So I stuck the barrel between his eyes. I looked at Rocco. I couldn’t shoot him. That’s what saved my life.”

Kulka walked home and told Mariko, then his girlfriend, he needed help.

He spent time in detox and rehab and found religion.

“I knew it was something I had to seek,” Kulka said. “For me, it’s ‘What Would Jesus Do?’ It’s love people, have compassion for others. That’s what I try to live by.”

STEPS OFF THE STREET IS MAKING A DIFFERENCE

Formerly homeless and a fentanyl addict, Gerald Jorgensen started pulling a wagon, sometimes two, with hockey bags full of clothes to hand out to people on the street a year and a half ago.

Now 55, Jorgensen has several volunteers who haul wagons full of food, hygiene products and clothing down routes on Rideau St. and Bank St. six times a month, and they’d like to do more.

There are also support meetings at drop-ins.

Sober more than two years, Jorgensen is making a difference. And, it feels good. Really good.

“I’d struggled with addictions, on and off, my whole life,” he said. “I had successes, but addiction stole opportunities. I stopped eating, I stopped drinking. I knew I wasn’t going to be alive much longer. It came to the point where I said, ‘God, save me or take me.’ ”

Three days later, a Salvation Army worker got him off the street and pointed him in the right direction.

According to its website, the mission of the Steps off the Street program, run through the Union City Church, “is to empower individuals experiencing homelessness to transition from the streets into addiction recovery. We achieve this through direct support, providing essential resources and fostering a sense of community. Approximately 60% of our volunteers are in recovery themselves, sharing lived experience to bring hope and build peer connections.”

“Because of the suffering I’ve been through, I can gain somebody’s trust in minutes,” Jorgensen said. “Society looks at them like throwaways, like they can’t be helped, like there’s no hope.

But we’ve seen all kinds of success stories.”

Asked about Kulka’s involvement, Jorgensen said: “He’s a big teddy bear, he’s got a big heart. It’s the same with most of the people who help us. I’ve seen (Kulka) pray for guys on the street. I see him talking to people. His line is, ‘Are you sick and tired of being sick and tired yet?’”

BEHIND THE CURTAIN AND THE DAMAGE DONE

Looking back and sorting out his past isn’t the best thing for Kulka’s mental health.

Damage in his frontal lobe of his brain shows he may have had strokes.

“The wrestling world, throwing yourself backward and taking a bump, that compounded everything,” said Kulka.

Kulka has sensitivity to light and gets headaches. He’s also got some blindness in his left eye.

Occasionally, he’s able to work with a client as a personal trainer.

“I can train somebody for an hour, then I have to go home and take a nap,” Kulka said. “I’ll have to rest the majority of the next day.

“My brain, my hard drive doesn’t have the ability to remember much, especially when it’s tired and fatigued. So, it’s this constant wave of exerting myself, whether it’s physical or mental, then figuring out how much time I need to recover so I can do something again.

“The most frustrating thing with the brain injury is people don’t see it. When you hear me talk now, you see me at my best. This is a time when I’ve made an appointment with you because I knew I was going to have a nap, I knew I was going to be able to eat and I knew I was going to be in a fairly good head space. But if we were talking two hours ago, you would have gotten a completely different me, you would have gotten somebody who could not continue a thought. You would have gotten somebody who could not articulate his thoughts.

“Because that guy usually stays home, nobody sees that. People see me, they go, ‘Oh, I saw Glenn. He looks great.’ And, for a 61-year-old man, I do. I still work out. I look good. But people don’t see those times when I can’t leave the house.

“We’re talking about a can’t-lift-your-arm kind of fatigue. You’re talking about a high-end athlete who was used to forcing himself to do things that weren’t comfortable. But I just can’t do it.

It’s very difficult. It took years to deal with the loss of who I was and who I am.

“When you have a brain injury, it’s more important to live in the now. You constantly readjust, refocus, reset and go forward. Life is too f—ing crazy, there’s a lot of crazy stuff going on. You can get caught up in that. For me, it’s put yourself in a positive situation, put yourself in the mindset to go help other people.”

EAT, SLEEP, TRY TO HELP, REPEAT

His involvement with Steps off the Street helps give Kulka purpose.

“I’m in a good place,” Kulka said. “I don’t have anything, I think I’m allergic to money. But as long as I can do this kind of work, I can fill my soul. With everything I’ve done in the sporting world, if I can be known for this and this only this, I’d be a very happy man.”

Kulka and Mariko, who have two children – Jaxson and Laura – split up 4 1/2 years ago after 23 years of marriage. In the aftermath, Kulka didn’t cope well, feeling alone and abandoned.

“It was a very dark place for me,” Kulka said.

Faith pulled him through and his relationship is again strong with his family – Jaxson is now 21 and Laura is 23. They live with him in Stittsville.

Kulka doesn’t have regrets.

“I made a shitload of bad decisions,” he said. “I don’t think you can go through life and worry about the choices you made. I lost my CFL pension in a housing deal, $90,000. I look at it as life lessons, things that had to happen for me to get where I am today.

“I’m in survival mode. I need to eat, I need a roof to live under. That’s all I need. The two days a week I volunteer to do this with S.O.S, it’s all I can do. If I had to leave my disability pension, I would only be able to work maybe eight hours or 10 hours a week. And I could never live or sustain myself on that.

“I sometimes look back and think, ‘Dude, just take it easy, you’ve done a lot, you don’t need to get all worked up about stuff anymore. A bad temper is not really an issue anymore. A lot of things I used to battle with are just not issues anymore, and I’m able to focus on the areas I need to focus on.

“You reap what you sow, I wouldn’t change a thing. Would I like to think I could have gone sober and done things a little different? Yes. But was that what I was destined to be? No.”

And it comes back to his faith and the want to help others.

“I had to let Jesus take the wheel,” Kulka said. “It saved my life. I would not be here if I had not found Jesus.”

And helping the homeless, people who are dealing with their own demons?

“That’s what Christ does to us. He puts us through all these tests so that when we find what we’re supposed to do in life, we’re prepared,” Kulka said. “When you look at what I had to go through just so I could pull a wagon around and hand a sandwich to somebody on the street, it’s a crazy journey when you think about it.

Related

- How a French rugby player became the second full-time female coach in CFL history

- Beer, cigars and tough love: Legendary 67’s coach Brian Kilrea reflects on 90 years