Ottawa city councillors rejected a motion to halt the

controversial Tewin community land development

planned for the city’s southeast end following a lengthy debate and numerous public delegations that spoke out against the project.

Bay ward Coun. Theresa Kavanagh

introduced the notice of motion on Oct. 1, saying council’s initial approval of

the Tewin project

was “rushed” and was done without proper consultation with appropriate Indigenous groups.

The motion was formally raised at the Oct. 15 planning and housing committee and highlighted a number of concerns with the Tewin development, including the lack of consultation with federally recognized First Nations, the lack of transit infrastructure and the costs associated with extending water mains and wastewater services to the “isolated” location in the rural southeast.

Kavanagh’s motion was narrowly defeated by a vote of five councillors in favour of halting Tewin and seven councillors against.

Couns. Cathy Curry, Laura Dudas, Clarke Kelly, Wilson Lo, Tim Tierney, Glen Gower and David Brown voted against the motion, while Couns. Kavanagh, Riley Brockington, Laine Johnson, Ariel Troster and chair Jeff Leiper voted in favour.

A second motion brought by Johnson, on behalf of Coun. Jessica Bradley, council’s liaison with the Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation, was defeated by the same voting lines.

Bradley had called for staff to hold further consultations with the 11 Algonquin First Nations and their two tribal councils and report back to the committee and council in the spring of 2026.

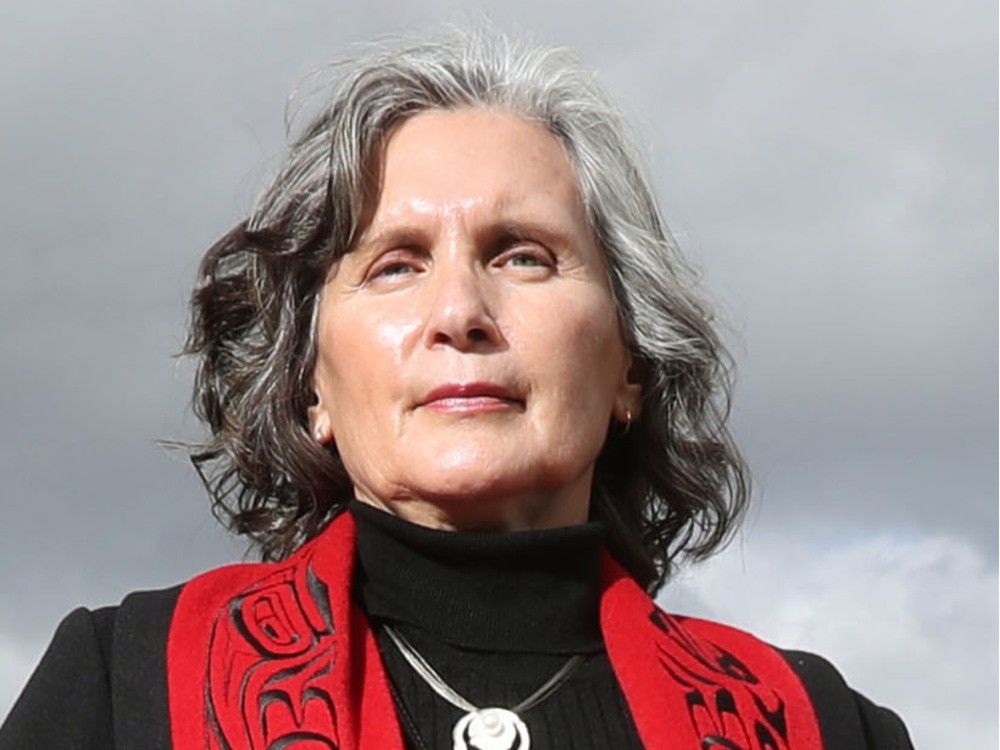

Representatives for 10 of the 11 Algonquin Anishinabeg First Nations spoke at the committee to voice their opposition to Tewin, including Savanna McGregor, Grand Chief of the Algonquin Anishinabe Nation Tribal Council, Chief Vicky Chief of Timiskaming First Nation and Grand Chief Lisa Robinson of the Algonquin Nation Secretariat.

Robinson told committee members they had an opportunity to amend the “planning error” and to “correct what could be a historic wrong,” she said.

“(Kavanagh’s) motion really speaks to what our Nation has been saying since February 2021. The Tewin project was pushed forward without proper consultation, without due diligence and without respect for our Algonquin rights holders, who are the true stewards of the land,” Robinson said.

The Anishinabeg chiefs objected to the city’s consultations with the Algonquins of Ontario (AOO), which Robinson described as “a corporate entity that was created for the specific purpose of negotiation, and that does not equate to having inherent Iand governance and constitutional status.”

The Algonquins of Ontario “do not represent the Anishinabeg Algonquin Nation,” Robinson said.

“By relying on the AOO as an Indigenous partner, the City of Ottawa has consulted the wrong party and has excluded the actual rights holder: the First Nations of the Anishinabe Algonquin Nation, our member communities. And that is not reconciliation, this is actually a continuation of colonial practice.”

Robinson said the city’s official plan and its reconciliation action plan demanded consultation with First Nations.

“Yet, when Tewin was added to the urban boundary, no consultation with Algonquin First Nations occurred, and that is a serious oversight — one that places the City of Ottawa at a legal and moral risk.”

Those in opposition to the project warned of potential legal risks if the city proceeded with the project, while proponents of the Tewin project warned of a lengthy battle at the Ontario Land Tribunal if council put a stop to the development.

Cyndi Rottenberg-Walker, a consultant at Urban Strategies Inc. and lead partner in

the Tewin development

, described the project as a “once-in-a-generation” opportunity to build a “complete community” with “tangible” design plans.

She said there was “no factual or policy basis” for Kavanagh’s motion and said it would be “contrary to good planning” to retract the deal.

If the motion had passed, Rottenberg-Walker said, Tewin proponents would have “no alternative but to reinstate through the Ontario Land Tribunal.”

She countered Kavanagh’s concerns of the

high cost of the project for Ottawa taxpayers

and reiterated the pledge from Taggart Group, the local developer, that “Tewin pays for Tewin.”

Jim Meness, Algonquins of Ontario executive director

and a member of the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation — the only federally-recognized First Nation within the AOO — presented a counterpoint to the Algonquin Nations who objected to the project moving ahead under the “guise” of reconciliation.

Meness said the Tewin project “is more than a development, it’s reconciliation in practice.”

“When people say it’s a failure of consultation, they erase decades of work that brought us here. The AOO have been negotiating in good faith since 1991 to reach a treaty … we have engaged in extensive consultations, not just with governments, but with other Algonquin communities and Indigenous organizations across the region.

“To dismiss that process, to suggest we were mistakenly consulted, is to repeat the old colonial story that we must forever justify our own existence,” he said.

Meness called that assertion “wrong and deeply hurtful.”

Wendy Jocko, former chief of the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation and a key proponent of the land deal, called Kavanagh’s motion “unfortunate interference in a project that addresses critical needs” for housing in Ottawa.

The project will create 15,000 new homes on 445 hectares of land and infrastructure costs “will be borne by the project itself,” she said.

Reversing council’s 2021 decision to green-light the project “would set back housing development planning by four years and create pressure to find alternative lands elsewhere at significant cost to taxpayers and with no guarantee of better outcomes.”

Tewin, Jocko said, “represents economic empowerment for Algonquin people.”

Related

- Communauto has a new car-sharing pilot in Ottawa. But how will it impact your street parking?

- New ByWard Market restaurants laud location — despite neighbourhood’s reputation