“Spend your whole day around ice cream, you can begin to grow philosophical,” warns an informant in “Shadow Ticket,” Thomas Pynchon’s madcap take on the hard-boiled detective novel. We’re in Cream City (Milwaukee), where dairy is not only big business, but also the basis for activities criminal, geopolitical and spiritual. The year is 1932. The Depression has hit, Prohibition is in full swing, and fascism is on the rise.

The 1930s backdrop makes “Shadow Ticket” a surprisingly timely intervention by the reclusive, recondite giant of American literature. If any decade has come to be treated as a touchstone for our troubled present, it’s the darkening tunnel of the ’30s. And considering the current renaissance of conspiratorial thinking — the Epstein files, QAnon — the time is ripe for a new novel by an author for whom paranoia is the default mode of existence.

The novel also comes hot on the heels of the release of Paul Thomas Anderson’s acclaimed “One Battle After Another,” a blockbuster movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio and based loosely on Pynchon’s 1990 novel, “Vineland.” Both Anderson’s film and Pynchon’s new book address us in our increasingly benighted present. Both combine a jaundiced eye with a comic sensibility, making shaggy heroes out of the hapless outcasts who refuse to just go along.

“Shadow Ticket”’s shaggy hero is Hicks McTaggart, a bumbling but sturdy private eye — a figure Pynchon readers will recognize from “Inherent Vice” (2009) and “Bleeding Edge” (2013) — in a city “where it seldom gets more serious than somebody stole somebody’s fish.” But Milwaukee is getting less sleepy by the day. Gang violence is spilling over from Chicago. A German U-boat is running contraband under the frozen surface of Lake Michigan. National Socialists have opened a bowling alley — New Nuremberg Lanes — on the edge of town, and, despite their protestations, their primary interest isn’t socializing.

As if there weren’t enough brewing in Milwaukee, Pynchon then drops most of these threads to transport readers across the Atlantic. Conscripted to find a local cheese heiress — a “hot tomato with a soul” — Hicks and the readers find themselves on a steamship headed for Hungary, where they will encounter British spies, Interpol double agents, an “asporter” (it’s not interesting enough to explain), a klezmer clarinetist on a secret mission to save European Jews, a “Versailles-compliant” golem, and a used autogyro salesman whose wife’s name, Glow Tripforth del Vasto, is a late addition to the shortlist of most absurd Pynchon names.

This might be too much material for any novelist to handle artfully, but that’s Pynchon for you. Why do 10 things when you can try to do 10,000?

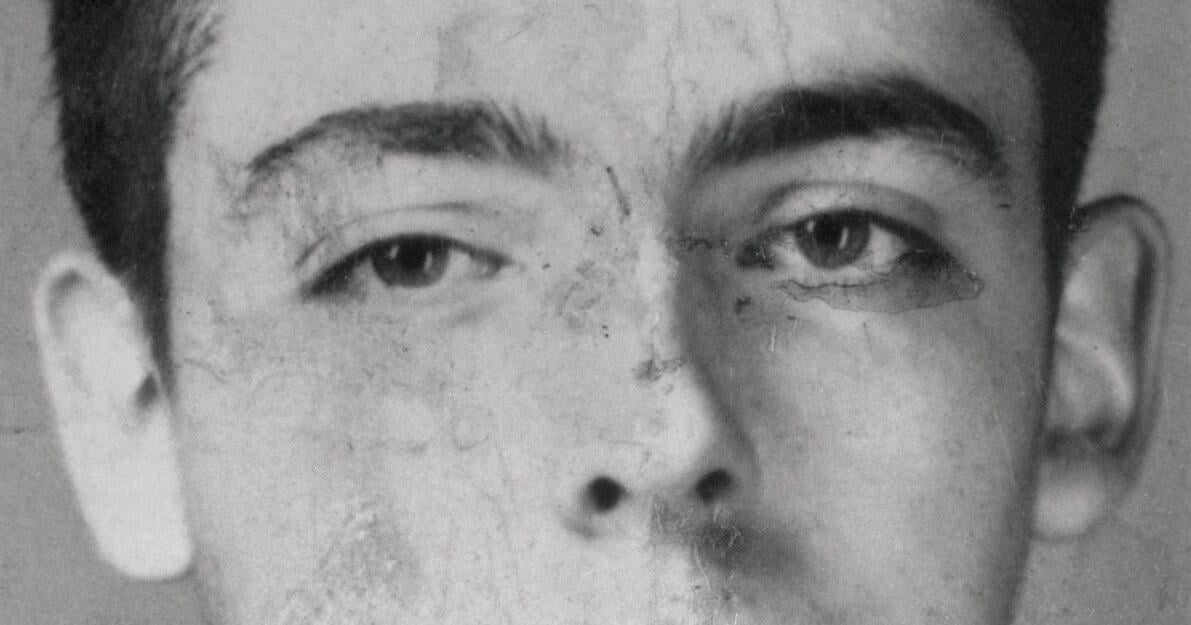

At 88, Pynchon is already long established as one of the most important and difficult postwar American writers. He made his name in the 1960s with his first novel “V.” (1963) — published the year John F. Kennedy was assassinated, to put his career into perspective — and a slim followup, “The Crying of Lot 49” (1966), before becoming truly unavoidable with “Gravity’s Rainbow” (1973), a colossal, blackly satirical, terrifying ode to the V2 rocket. In 1997, “Mason & Dixon” — his most humane novel — won over many of the remaining doubters.

Even so, Pynchon has his detractors. The critic James Wood has called his later work “juvenile vaudeville.” A Guardian review of “Bleeding Edge” observes that “Pynchon seems to have eliminated not just the creaky conventions of the realist novel, but most of the human interest, too.” The detractors are on to something. “Shadow Ticket” is shorter than Pynchon’s major works, and yet it too becomes so zany and convoluted that the reader is often left bewildered by the onslaught of underdeveloped ideas and wearied by the never-ending japes.

But fairness also requires acknowledging that Pynchon is unusually brilliant, working alone in a genre of his own devising, and a great comic writer in the tradition of Aristophanes and Rabelais. As frustrating as he can be, his obvious virtues make it difficult to dismiss him entirely. Like all of Pynchon’s work, “Shadow Ticket” is a feast of language, brimful of clever jokes (and knowingly dumb ones), barely detectable but pregnant historical curios (about, say, the politics of sans serif fonts or the origins of the modern zoo), perfectly calibrated dialogue, inane musical numbers and joyfully descriptive lists.

One of my favourite such lists came as Hicks — falling deeper and deeper into European entanglements — dreams of a return to Milwaukee, with its “brat smoke from a lunch wagon grill, some kid practicing accordion through an open window, first snow coming into town off the prairie, barrooms where the smell of beer is generations deep … fried perch and coleslaw on Friday nights. Buttermilk crullers, goes without saying.” This is heady, sensory stuff. Even in a faux-lyrical mode, Pynchon can make a person want to pick up and move to Milwaukee.

But he can’t just let the fantasy stand. A quiet bourgeois life has never been Pynchon’s solution to what ails us. Hicks has to come to the cold realization that there’s no returning to this “place of clarity, still snoozy and safe,” if it ever existed. There’s only the open road and the unflagging quest: to remain decent, to remain just out of reach of the powers that threaten to enlist us in their great conspiracy of fear and greed. If Pynchon has something to say to us in these dark times, perhaps that’s it.

Having grown a little philosophical, Hicks’s friend Stuffy puts it this way: “the real thing, what if that’s only when they’re comin after you for somethin? But they haven’t caught you yet. So for a while, as long as you stay on the run, that’s the only time you’re really free?”

It’s hard not to wish that Pynchon had, for once, deployed his galactic imagination in the direction of something more coherent and satisfying. But it’s just as hard not to admire his dogged insistence on staying on the run. At 88, he hasn’t been caught yet.