For five years, Ottawa’s William Baldwin bent over his writing desk and inscribed, for posterity, the name of every Canadian who died in uniform during the First World War.

A commercial artist, Baldwin had been chosen for the task because of his precise and expressive calligraphy.

Between 1932 and 1937, he would painstakingly inscribe onto hand-made sheets of vellum the names, ranks, decorations and units of each of the 66,655 Canadians who died during the war. A single mistake — a smudge, an incorrect rank, a name out of alphabetical order — could ruin weeks of work.

Ultimately, the pages — more than 600 in all — would be illustrated with laurels, illuminated with gold and bound in Moroccan leather to create Canada’s first Book of Remembrance.

Nine months after the First World War Book of Remembrance was officially dedicated on Parliament Hill, Squadron Leader William Baldwin died when his bomber was shot down over Berlin.

He was 33.

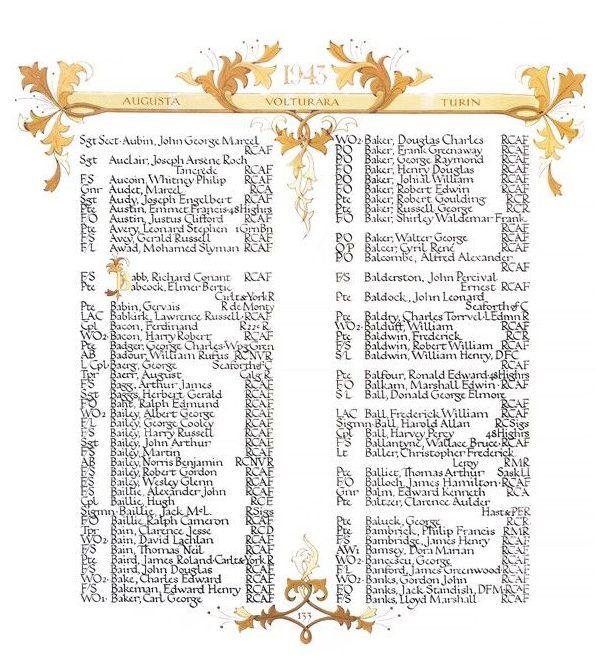

Inscribed by another hand, Baldwin’s name appears in Canada’s second Book of Remembrance, the one that commemorates this country’s Second World War dead.

“It’s a pretty remarkable story: the guy who wrote out 66,000 names for the first book would himself be written into the second book,” said Dave O’Malley, a graphic designer and amateur historian

who recently wrote about Baldwin for the charitable organization, Vintage Wings of Canada

.

He came across Baldwin’s story while compiling information he used to

map the homes of Ottawa’s war dead

.

“I found his story really compelling, and I wanted to tell it,” O’Malley said.

William Henry Baldwin was born Jan. 12, 1910 in Ottawa. His father was chief mechanic in the federal government’s printing bureau.

Baldwin grew up with five siblings on Fifth Avenue in the Glebe, and attended Glebe Collegiate Institute, where he played basketball, rugby and tennis. He ran track and skied, while developing an interest in draughting, mapping and art.

Baldwin left school at 18, and worked at a life insurance company before taking a job in the photographic section of the Royal Canadian Air Force. When that ended, he applied for a job with a new government office authorized by Parliament in 1932 to create the First World War Book of Remembrance.

The book was the solution to a problem. Government planners originally intended to carve the names of the country’s war dead onto the walls of the Peace Tower’s Memorial Chamber, but they soon realized there would not be enough wall space. The official historian of the

Canadian Expeditionary Force

, Col. Archer Fortescue Duguid, suggested the names be inscribed in a memorial book instead.

Scottish-born artist James Purves, who served in the Royal Flying Corp during the First World War, was put in charge of creating the Book of Remembrance and handed a $35,000 budget.

He hired Baldwin to produce the manuscript after reviewing his writing samples. Baldwin had no professional training as a calligrapher, but his precise Roman lettering met Purves’ approval.

Baldwin went to work in an office in the National Research Council building on Sussex Drive fitted out with special drawing tables, lamps and humidifiers (to keep the calfskin vellum supple).

A National Defence Department committee was handed the task of compiling the names that Baldwin would then inscribe.

Inevitably, with so many names, there were omissions: An addendum was eventually created with 80 names not in their rightful place.

“I can’t help but wonder about what Baldwin thought as he transcribed each name, rank and unit — 66,655 times in all,” O’Malley wrote of Baldwin’s “Sisyphean-like task.” “Did he wonder who these men and women were? Where they lived? Their families? Their futures?

“What was he thinking when he inscribed the names of each of the 27 Baldwins or the two William Baldwins he found in the list? Did he wonder if he had the mettle to do what these men did before their deaths? By the end of his five years of painstaking work, he, more than most non-combatants, must have understood the staggering cost of a total war.”

When Baldwin completed his pages, they were handed to artists who illustrated, decorated and bound them.

The project would take twice as long — 10 years — and cost more than twice as much as originally anticipated.

In fact, Purves had died and Baldwin had already joined the Second World War by the time the completed Book of Remembrance was put on public display on Nov. 11, 1942 in the Peace Tower’s Memorial Chamber.

Baldwin enlisted in the RCAF in May 1940 as Nazi forces swept across continental Europe. He was 30 years old, and had just been laid off from a job as a commercial artist with the federal government’s National Parks bureau.

Baldwin volunteered to be an air gunner or navigator.

He trained as an air observer, but he did not take to navigation readily, and consistently graduated toward the bottom of his class. “Hard worker. Slow to grasp things,” noted one assessment.

Nonetheless, he was posted to the RCAF’s 405 Squadron in September 1941, and flew his first combat mission one month later over occupied Belgium. Bomber Command was then the principal instrument for carrying the war to Germany.

Baldwin flew bombing missions against cities such as Frankfurt, Essen, Düsseldorf, Hanover and Berlin. His crew bombed Nazi submarine pens in the south of France.

He also took part in the first “thousand bomber raid” on May 31, 1942, when 1,103 bombers pounded Cologne in the largest attack of its kind to that point in the war.

By October 1942, Baldwin had completed his full tour of duty — 32 missions — and was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross as “a navigator of exceptional ability” who showed courage and initiative. “His unfailing cheerfulness and optimism, in spite of all hazards, has proved a source of inspiration,” his citation reads.

He was promoted to squadron leader and returned home to Ottawa in December 1942 to celebrate Christmas with his family.

Since he had completed a full tour of duty, Baldwin could have taken an RCAF desk job or an assignment at an air training unit, but he instead signed up for another tour of duty after an extended leave.

On his return to 405 Squadron, Baldwin joined a new, younger crew. The first mission of his second tour took him on a raid to Berlin, the most heavily defended city in Germany, on the night of Aug. 23, 1943. Baldwin’s Halifax bomber and its crew of seven were pursued and shot down by a Luftwaffe night fighter.

Baldwin managed to parachute from the doomed plane, but he did not survive the jump. He is buried in the Berlin War Cemetery.

The name of William Henry Baldwin is inscribed onto page 133 of Canada’s Second World War Book of Remembrance.

Related

- How the Château Laurier helped win the Second World War

- Canadian military will rely on an army of public servants to boost its ranks by 300,000