We apologize, but this video has failed to load.

A case playing out in an Ottawa courtroom presents not just the heavy burden of caring for an ailing loved one, but also the moral and legal considerations when love leads to homicide.

When Carol Berthiaume arrived at the Ottawa home of Philippe Hébert and Richard Rutherford the day before Good Friday 2022, she was immediately struck by the state of the place.

It was immaculate.

Not only that, it was beautifully decorated for Easter, including a needlepoint runner laid out on a central table that Hébert, then 69, had embroidered himself to celebrate the holiday.

THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Unlimited digital access to the Ottawa Citizen.

- Analysis on all things Ottawa by Bruce Deachman, Elizabeth Payne, David Pugliese, and others, award-winning newsletters and virtual events.

- Opportunity to engage with our commenting community.

- Ottawa Citizen ePaper.

- Ottawa Citizen App.

SUBSCRIBE TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Exclusive articles from Elizabeth Payne, David Pugliese, Andrew Duffy, Bruce Deachman and others. Plus, food reviews and event listings in the weekly newsletter, Ottawa, Out of Office.

- Unlimited online access to Ottawa Citizen and 15 news sites with one account.

- Ottawa Citizen ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles, including the New York Times Crossword.

- Support local journalism.

REGISTER / SIGN IN TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

THIS ARTICLE IS FREE TO READ REGISTER TO UNLOCK.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments

- Enjoy additional articles per month

- Get email updates from your favourite authors

Sign In or Create an Account

or

Hébert and Rutherford had lived here for nearly 40 years, settling in not long after moving from Winnipeg, where Rutherford had been the longtime principal dancer at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet.

The Evening Citizen

The Ottawa Citizen’s best journalism, delivered directly to your inbox by 7 p.m. on weekdays.

By signing up you consent to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc.

Thanks for signing up!

A welcome email is on its way. If you don’t see it, please check your junk folder.

The next issue of The Evening Citizen will soon be in your inbox.

We encountered an issue signing you up. Please try again

Now 87, he was spending as much as 20 hours a day in bed, with Hébert his main caregiver.

It was a big job. Once in exquisite shape, Rutherford’s body was failing. He had prostate cancer, diabetes, and mobility challenges that made it difficult for him to use the stairs. Often he’d put off getting out of bed until 5 p.m., at which point Hébert assisted him down the stairs to watch his favourite TV show, The Big Bang Theory. He also suffered from vascular dementia and showed signs of depression. He’d lost his driver’s licence, and had been the household’s only driver.

Hébert, desperate for help, had called Berthiaume, a care coordinator with the local agency in charge of delivering home and community-care services. She was here to assess whether Rutherford could decide on his own about moving into long-term care — or whether someone should decide for him.

No one knew it when she arrived that day, but Rutherford would not live to see that Easter.

Berthiaume conducted the assessment in the bedroom, and the two men joked about seating her in a folding “director’s chair,” like those found on movie sets.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

“They laughed about it,” Berthiaume later recalled, laughing at the memory herself.

She sat directly opposite Rutherford, while Hébert found a place nearby, on the bed.

“Tell me about yourself,” Berthiaume remembered asking Rutherford, “and he says, ‘I don’t know what to say.’ “ But then he launched in, describing a full, rewarding life of dance and travelling the world.

And yet he did not see his career as the pinnacle of his life’s work. As Berthiaume recalled it, “he said that living with Philippe is the greatest thing to ever happen.“

When a neighbour arrived, interrupting the meeting to deliver a box of Farm Boy cookies for Easter, the two men ate them with relish.

Despite the light-hearted atmosphere, Hébert seemed to have come to a decision about his husband. Though Rutherford had long opposed the idea, Hébert had earlier told Berthiaume he was ready to seriously look into moving him into long-term care: “I think it’s come to that point.”

Perhaps sensing this new resolve, Rutherford had made himself clear to Berthiaume before the assessment even began, saying that “he would rather die than leave his home.”

Berthiaume felt Rutherford was speaking “figuratively, in the sense that he was telling me that he just wasn’t wanting it.”

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

But dying is exactly what came to pass.

In the hours after Berthiaume departed the home that afternoon, Hébert suffocated Rutherford using the plastic portion of a fresh incontinence pad.

Hébert then made several attempts at dying by suicide.

The account presented here of what happened in the couple’s home in April 2022 is drawn from a series of sentencing hearings at the Ottawa courthouse in September and January.

It is uncontested that he committed the homicide after Rutherford told him he wanted to die. Initially charged with second-degree murder, Hébert has pleaded guilty to manslaughter.

But the issues canvassed during these proceedings can be summed up in a single question: should Hébert, who has lived under house arrest for most of the last four years, go to prison?

The Hébert case lays out in stark terms not just the heavy burden of caring for an elderly, ailing loved one at home — especially when that care took place during the COVID-19 pandemic — but also the moral and legal considerations that come into play when love leads to homicide.

The Hébert matter is one of just a handful of so-called “mercy killing”-type cases to come before the courts since the federal government passed medical assistance in dying, or MAID, legislation in 2016.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Twenty-five years ago, Robert Latimer began serving 10 years following a second-degree murder conviction in the death of his 12-year-old daughter Tracy. A quadriplegic with the mental capacity of a four-month-old, she lived in “incessant agony,” according to her father, who killed her by placing her in his truck and venting its fumes into the cab.

Latimer divided Canadians and helped shape the debate that gave rise to MAID. And yet the courts have for years been reluctant to hammer ‘mercy killers’ with long jail terms.

And, as Hébert’s counsel, the leading Ottawa defence lawyer Solomon Friedman, pointed out during his submissions this month, that reluctance has proven even more stubborn in recent years.

Friedman also noted that “mercy killings” typically do not involve consent.

“Prior to the MAID regime in Canada, there was no defence of consent,” Friedman argued, adding “that has changed — we are in a different society, we are in a different place now.”

***

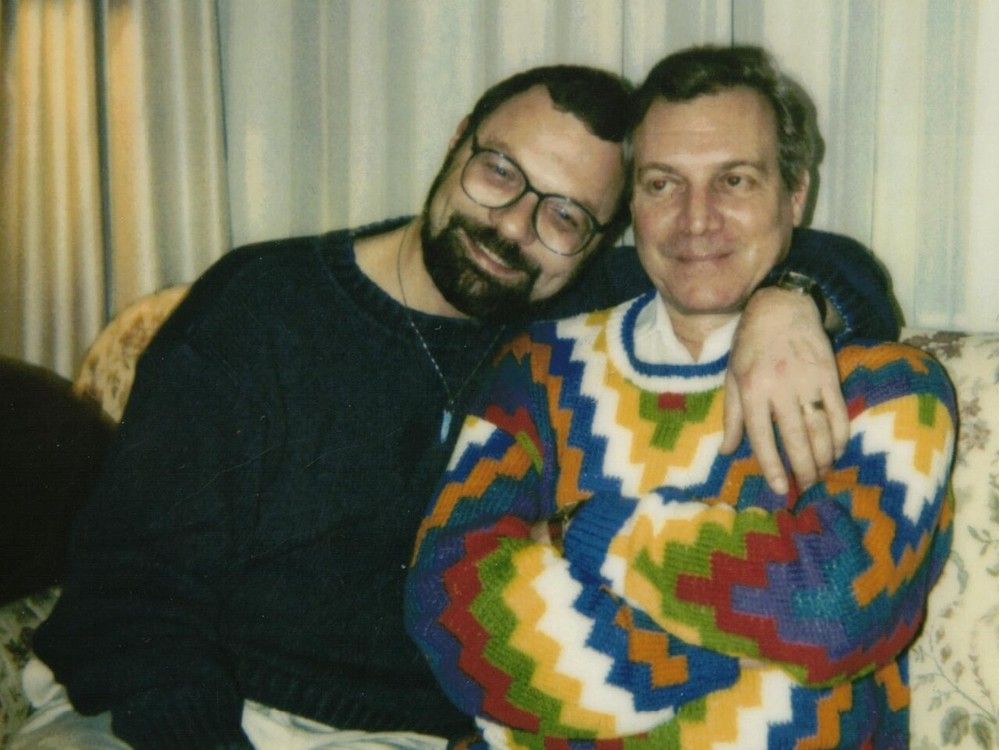

Philippe Hébert and Richard Rutherford first met at The Happenings Social Club, a gay bar in Winnipeg, in 1976.

Hébert was from small-town St-Pierre-Jolys and grew up one of nine children in a Franco-Manitoban family. His father worked construction, his mother ran a restaurant. Hébert left high school in Grade 10 and went on to become an orderly at St. Boniface Hospital.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Rutherford’s background could not have been more different. Almost 20 years older than Hébert, he was from Augusta, Ga., in the American South. Though he was raised poor in a broken family and endured bullying, his obvious talent led him first to study at the School of American Ballet in New York, then to the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, where he remained for 20 years.

“I had no idea of where Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada was and didn’t really care,” Rutherford told one interviewer. “I just knew I was going to dance and that was all that mattered.”

By the time he and Hébert met, Rutherford was associate artistic director of the company.

It was a whirlwind romance: within the year, Hébert was following his new romantic partner across the country to live in Ottawa, where Rutherford had accepted a job at the Canada Council for the Arts. Hébert became a physiotherapy assistant at The Ottawa Hospital Rehabilitation Centre.

From the 1980s, their home on Smyth Road became a hub for Ottawa’s gay and arts communities.

Both men gardened — Rutherford filled the front and back yards with exotic plants — while Hébert did the cooking, becoming especially known for his baking.

Hébert was quiet, self-effacing, and often deferred to Rutherford.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Rutherford, meanwhile, was a proud man, extroverted, and often stubborn.

After he retired, he served as president of the board of directors of the Canadian Tribute to Human Rights. When he and Hébert married on April 1, 2006, less than a year following Canada’s legalization of same-sex marriage, the wedding party visited the human rights monument Rutherford had helped establish.

It is located at the corner of Lisgar and Elgin streets — across the street from the courthouse where Hébert pleaded guilty to Rutherford’s manslaughter.

“Tell me about yourself,” Berthiaume asked Rutherford as she conducted her assessment in their home.

“I’ve travelled all over the world, from Flin Flon to Moscow,” Rutherford replied. “But the greatest part of my life has been living with Philippe.”

In court, at this point in the testimony, a woman sitting in the second row of the gallery behind Hébert smiled and reached out to rub his shoulders. Hébert bowed his head and exhaled.

Surveying a lifetime of memories was part of what kept Rutherford in his bed.

“The words I remember Richard telling me was that when he was lying in bed, his mind would just drift and lots of thoughts would come through his mind,” Berthiaume told the court. “I’m sure he was probably dreaming about his lovely career in the ballet.“

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

But Berthiaume, trained as a registered nurse, told the court that failing to get out of bed and engage in the activities of daily living posed significant health problems.

Rutherford, a diabetic, needed three proper meals a day to keep up with his medications and maintain his exercises, lest he become even more vulnerable to falls.

He would “cruise” the house when out of bed, clutching at furniture or the walls, and refused to use a walker or cane. He often begged off showering, limiting his washing up to the sink and claiming that he could maintain himself.

Hébert, a retired physiotherapy assistant, bristled at his own inability to coax his husband up and into his prescribed routine.

He was managing a gruelling caregiving load. He kept the house, prepared the meals, and had to get Rutherford into the bathroom for toileting and to keep him clean and shaved.

For a time, Rutherford’s prostate issues required him to wear a catheter, which would frequently disconnect, soiling the bed.

With the removal of the catheter, Rutherford made more frequent trips to the bathroom each night, obliging Hébert to accompany him and prevent him from falling.

Hébert got little sleep.

In the months leading up to Easter, Berthiaume encouraged the couple to accept more personal-care workers. They could help with Rutherford’s routine and allow Hébert some rest.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Rutherford was not interested. He believed he could look after himself, adding that Hébert was available to step in when needed.

But Hébert was always needed.

“I don’t believe that Richard saw the stress that Philippe was under — I don’t think he recognized it, to be honest,“ Berthiaume said.

Under what circumstances would he consider going into long-term care, Berthiaume asked.

“I don’t want to think about it, as I don’t want to go,“ Rutherford replied.

Berthiaume ultimately deemed him incapable for the purposes of choosing for himself whether to enter long-term care, saying he “wasn’t able to foresee the consequences of his actions.”

“I felt confident with the decision that he was incapable,” she told the court. “And I did give him what my findings were and I asked him if he had any concerns or questions about this finding. And at that particular time, he said ‘no.’”

Asked about how Rutherford reacted, she recalled that “he was not upset at all. He just seemed to be accepting of my decision.”

Berthiaume also observed that Hébert appeared worn out, tired, frustrated.

The determination of incapacity left the decision about whether Rutherford would remain living at the house on Smyth Road entirely with Hébert, Rutherford’s power of attorney for personal care.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

But was Rutherford truly incapable of deciding? To Hébert, Rutherford seemed so sure of himself and his desire not to leave their home.

According to Hébert’s testimony, Rutherford had once inquired with the family doctor he and Hébert shared about the possibility of MAID, but the discussion was inconclusive, and the couple felt sure Rutherford would not be eligible. They did not follow up.

As Berthiaume’s assessment was winding down, Hébert asked whether Rutherford needed to use the bathroom. Rutherford was adamant he did not. “Are you sure,“ said Hébert. “You’ve been sitting in the chair for a while?” Rutherford instead stood and walked to their bedroom window.

“There was, I think, a vase with tulips in it,“ Berthiaume told the court. “He looked out of the window and he made some comment about how much he loved looking out, the flowers, the spring, and how much he loved, I think, being in his home.

”And so he then proceeded to lie down.“

Soon, Hébert and Berthiaume were downstairs discussing next steps.

Berthiaume had arranged for more personal-support workers to begin visiting them immediately after the Easter long weekend.

Hébert signed the application formally, beginning the process of entering Rutherford into long-term care. Hébert’s sister Annette, a retired nurse, was due to arrive within days to help them look for the right situation for Rutherford.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

But just then, they heard Rutherford’s voice calling to Hébert from upstairs.

He had tried to make it to the toilet himself but had soiled himself.

In this way, the visit was abruptly ended. It was 4:20 p.m. on the Thursday before Good Friday.

Sometime later that evening, after Rutherford and Hébert had gone to bed, Hébert was awoken.

It was the middle of the night. Rutherford was sitting on his side of the bed, crying.

What was it?

He did not want to go to a home, Rutherford told Hébert.

“I would rather die,“ Rutherford repeated. “I’m tired of living like this.“

“He had mentioned this many times previous to this,“ Hébert told the court, recounting what happened that night during testimony from the witness box.

“Well, I can help you,“ Hébert told his husband, adding: “I don’t want to go on without you, either.“

****

Now in his early 70s, Hébert is an avuncular, slow-moving, bearded man in glasses, with a pronounced twitch in his cheek. In court, he appeared confused, particularly with respect to timelines and his role in the decision-making around Rutherford’s care. He fumbled with documents handed him to refresh his memory.

He wore an intricate needlepoint vest he embroidered himself with a crescent moon on one side, a fiery sun on the other. (One member of Rutherford and Hébert’s circle wrote in a letter later read out in court that Rutherford was like a blazing sun, Hébert the moon reflecting that sun’s light.)

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Hébert said he could not say exactly when his nighttime discussion with Rutherford took place:

“It was early in the morning, I gather,“ Hébert said. “I couldn’t tell you if it was morning or night or day … I still imagine myself at night.“

He continued: “I got out of bed and decided I needed to do what I had to do.“

Rutherford now appeared to be asleep. “I’m assuming he was asleep,“ Hébert said. “Maybe not.“

He retrieved a clean incontinence pad, identified in court documents as “pee pad 1-BH-8,” and held it over Rutherford’s face “until he wasn’t moving anymore.“ Police would later find a pad near the bed with what appeared to be the impression of a human face visible in the plastic.

“I didn’t enjoy doing what I did and I still don’t,“ before later adding: “It upsets me that here you love someone as much as I loved Richard and it’s made out like—“

Hébert struck the side of the witness box with his fist.

“I wasn’t being mean,“ he said, his voice raised, his hand on his forehead.

The proceedings paused as Hébert cried, breathing heavily.

“Do you wish to continue on, sir?” Justice Phillips asked after a period of time.

“Let’s do it,“ Hébert said.

“Did Richard fight back,“ Crown Elena Davies asked Hébert.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

“No.“

“You don’t wake Richard up and say are you sure you want to do this?“

“No,“ Hébert answered. “I did say that I loved him as I was holding the thing on his face.“

Then Hébert tried to end his own life. He went to the bathroom and cut his wrist. When he did not find satisfaction with this method he retrieved a propane tank from the barbecue and carried it into the bedroom in an attempt at gas asphyxiation, but this too proved unsuccessful.

Hébert returned the tank to the barbecue before making a similar attempt with butane gas.

He finally ingested ant poison and returned to bed, lying next to Rutherford.

“I waited for death to come — but it didn’t come,” Hébert told the court.

Once he understood he would not die, he got up and dialled 9-1-1.

Why did he telephone the police?

“I knew I had done something wrong and I needed to confess,“ Hébert told the court.

“You don’t regret ending Richard’s life?“ the Crown prosecutor asked him.

“No,“ he replied. “I would do it again.“

It was shortly after 3 p.m. when Hébert greeted police and paramedics outside the home. He was wearing a T-shirt, underwear and Croc sandals.

“I still thought it was evening or nighttime because it was dark,“ Hébert recalled. “Maybe I was slowly going to the other side, I don’t know.”

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

***

Manslaughter convictions leave judges wide latitude in sentencing, from no prison up to life behind bars.

Crown prosecutors are seeking six years of incarceration.

Solomon Friedman, representing Hébert, said he is bound by a plea agreement struck with the Crown to ask for no less than two years, but he asserted that a sentence along the lines of that sought by the Crown would “shock the conscience of Canadians.”

Friedman argued that cases with similar facts to Hébert’s have, in recent years, ended in conditional sentences — in other words, with no jail time.

During his sentencing submissions, Friedman cited a number of such cases — both those that preceded and those that came after the advent of MAID. All showed that, with the notable exception of Latimer, Canadian courts have rarely sentenced mercy killers to serious jail time.

“Mr. Hébert poses absolutely no risk to any person in the community,” Friedman said.

Davies, the Crown, meanwhile, argued that the courts had the responsibility in sentencing of denouncing Rutherford’s slaying and deterring other would-be offenders from taking similar action.

Davies also argued that Hébert, in killing Rutherford, “took the law into his own hands.”

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Superior Court Justice Kevin Phillips will deliver the sentence in this case on Feb. 17.

***

It was only days before Rutherford’s death when Hébert called a neighbour in tears and asked if he would come over to look at his husband, according to court testimony.

Rutherford was not doing well. When the neighbour arrived in the bedroom, he thought Rutherford might be dead. Hébert was so beside himself that the neighbour called for an ambulance.

The couple spent days in the hospital until Rutherford recovered well enough that doctors said they could head back home. The same neighbour drove to the hospital to pick the couple up.

Rutherford and Hébert got into the car. As they were about to leave the hospital, Rutherford told his neighbour: “This is the last time I see the inside of this place.”

With files from Andrew Duffy