Several councillors on Ottawa’s built heritage committee are calling for more legislative tools for the city to compel owners of designated heritage buildings to restore and develop properties that have been sitting vacant, derelict and deteriorating.

Somerset Coun. Ariel Troster suggested a vacant commercial unit tax — similar to the residential vacant unit tax that was introduced in 2022 — as a further incentive for commercial property owners to restore and return their buildings to the market.

The vacant unit tax for residential properties was designed to encourage homeowners to maintain, occupy or rent their properties in an effort to increase the supply of available housing.

According to the most recent data, there were 4,140 vacant units in single and semi-detached homes, townhomes, condos and multi-family buildings (excluding large apartment buildings) in 2023, about 1.2 per cent of all homes in Ottawa.

At least 1,607 of those previously vacant units were returned to the market between 2022 and 2023 and the program generated $14.3 million in tax revenue in 2023, with net proceeds going to the city’s affordable housing reserve.

A similar tax on commercial properties would act as a “disincentive” for owners to allow heritage buildings to fall victim to “demolition by neglect,” Troster said.

“There might be the owner of an abandoned heritage property, and, frankly, they don’t want to meet the heritage requirements, so they let the building sit there in the hope that it’ll fall apart and they’ll be allowed to demolish it,” Troster said.

“One developer told me in a meeting that’s exactly what he intends to do — it was actually quite astounding to hear that directly from him — but it’s not an uncommon problem,” she said.

“The other issue we have are empty storefronts on main streets like Bank Street, where, in some cases, the landlord would rather sit on the property and leave it empty rather than charge a slightly lower rent and allow an incubator business or a local business to use that space.”

Troster said the city had limited incentives like heritage restoration grants to “gently nudge” owners to maintain their heritage properties.

“We have the carrot, but we don’t have the stick,” she said. “And my community is incredibly fed up and there’s an enormous amount of frustration. They keep asking me, ‘What can you do to force the developer to do something?’ And I don’t have a tool. So I think this is a systemic problem, particularly in downtown Ottawa and lots of other downtowns across the country.”

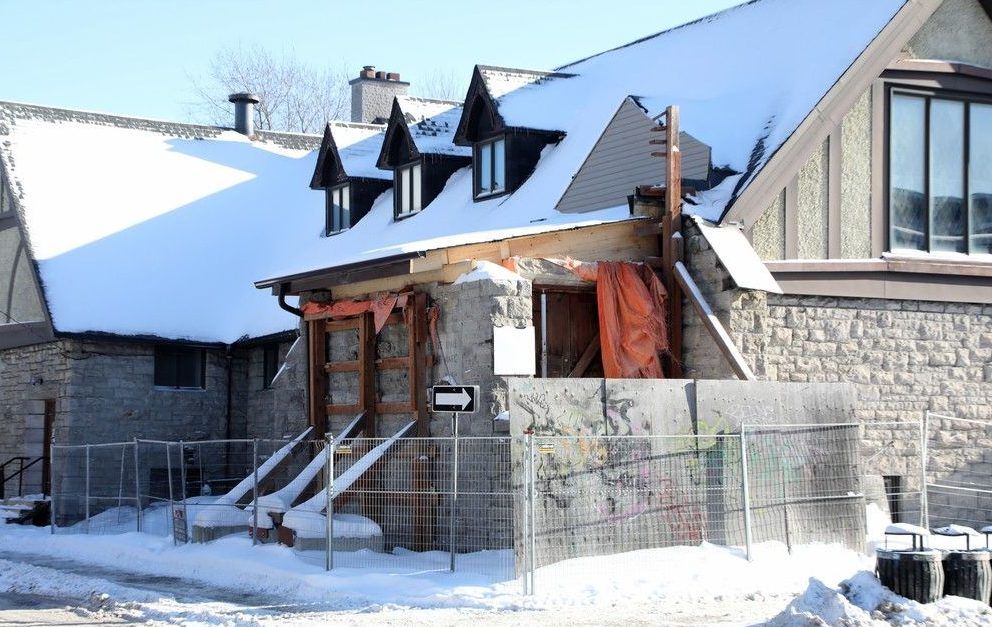

Somerset House — 352 Somerset St. W.

Somerset House — the distinctive three-storey red brick building at the corner of Bank Street and Somerset Street West — has long been labelled by councillors and by citizens’ groups like Heritage Ottawa as the “poster child for demolition by neglect.”

The building at 352 Somerset St. W. has been sitting vacant and deteriorating since a partial collapse during short-lived renovations in 2007, when an excavator accidentally damaged a support column.

The city’s heritage planning staff expressed “cautious optimism” in May 2025

, when long-awaited restoration work finally commenced, with the first crews onsite since the partially-collapsed east wing was dismantled and removed in 2016.

The city granted a permit in the fall of 2025 for building owner Tony Shahrasebi to pour concrete to shore up the building’s foundation. In an update to the city’s built heritage committee on Jan. 22, heritage planning program manager Lesley Collins said work on the foundation was expected to begin again in February.

An above-grade permit is “ready for issuance” for the remainder of the redevelopment project, which is expected to extend over several years, Collins told the committee.

“We expect that there may be some stops and starts in the work, but work is happening, and that’s a positive thing,” she said.

The outlook is not as rosy for other derelict heritage buildings where work has either stalled or is yet to begin.

“Obviously, the poster child for demolition by neglect is Somerset House, but 330 Gilmour St. is pretty close behind,” Troster said.

Ottawa Public School Board administration building — 330 Gilmour St.

The sprawling heritage building at 330 Gilmour St. — taking up most of a city block in Centretown between Metcalfe and O’Connor streets — was once home to administrative offices for the former Ottawa Public School Board.

Built in 1922, the building has been vacant since the land was purchased in 2001 by Ashcroft Homes, which received permission to construct a retirement home in 2008 following a lengthy approvals process.

Ashcroft Homes Group was forced into receivership in 2025

, with its extensive local real-estate portfolio under the control of Toronto-base receiver KSV Restructuring Ltd.

Some of the former Ashcroft holdings have since been sold to other buyers, though the Gilmour Street property was not among those listed for sale.

The city has, meanwhile, issued several orders related to a building condition assessment. Collins told the built heritage committee that city staff were in the process of contracting out the building condition assessment last fall when the owner stepped in and agreed to complete the report.

Staff provided “guidance” to the engineer hired to complete the assessment and the draft report was submitted earlier in January, Collins said.

“It has identified some urgent issues that require pedestrian protection along Lewis Street from fall hazards related to some of the masonry work on the building,” Collins said, but that repair work cannot be completed until the spring.

The city demanded protective fencing be installed along Lewis Street as an immediate measure to prevent debris from falling onto the sidewalk.

“There is masonry work that needs to be completed in order to prevent the pedestrian hazard of falling bricks and stones, and that cannot be completed until the weather is permitting,” Collins said. “If the repairs are not completed by the owner in the spring, the city will be taking action to undertake this work on their behalf.”

While the fencing is the most immediate need, the building condition report also identified “a wide variety of other issues,” Collins said. Staff are working to determine whether any other orders will be issued to conserve the property.

“That building has been basically left to rot for the last 20 years by the developer, and there was urgent work that needs to be done and the developer is currently in receivership,” Troster said. “The city reached the point where some of those repairs needed to urgently be done so that they didn’t cause any safety hazards, so the city is making those repairs and charging the developer.

“It’s one of the only tools we have if a property has fallen into such disrepair that it’s posing a threat to the health and safety of the community. I think we can and should do much better than that,” she said.

“It’s terrible that 330 Gilmour essentially takes up a whole block in Centretown and it’s become a blight. It’s a space that could be used so much better, but this (measure) is the bare minimum, and it’s also one of the only tools we have as any sort of penalty for these kinds of abandoned properties.”

227 to 237 St. Patrick St.

While councillors and staff have expressed frustration with the limited legislative tools, some owners of heritage properties have also vented their frustration in adhering to the stringent specifications that come with heritage designations.

Council reluctantly approved the demolition of a row of three houses in heritage Lowertown in 2024

under the proviso that, if and when they were rebuilt, the replacements would “consider the artistic expression of the existing buildings and the contribution they made to the streetscape.”

The vacant homes in the Lowertown West Heritage Conservation District contribute to the “early working-class residential character of Lowertown,” according to a staff report.

The buildings have continued to deteriorate since 2024 and Collins said the city’s building code services issued orders to “remedy unsafe buildings” on Jan. 21.

According to Collins, heritage planning staff recommended that owner Brian Dagenais enter into an agreement with the city “to ensure interim landscaping of the property once demolition is complete,” and to prohibit interim use of the properties until they were redeveloped.

Dagenais, who purchased the buildings in 2019, said in an interview that “the demolition isn’t complete, so there’s no agreement to enter into until or if or unless it’s complete.”

Dagenais said he received a phone call from staff nearly a year ago suggesting the city could tear down the buildings on his behalf and bill him for the work.

“I gave my verbal approval,” he said. “We were supportive of city doing it.”

Dagenais lamented the process in dealing with the city

, however, and said he would be on the hook for “hundreds of thousands of dollars” and would be required to jump through numerous “hoops” to redevelop the properties.

“Our project was not exactly controversial,” he said, with his group proposing to replace the buildings with similar-sized residential buildings.

“We had no problem emulating what used to be there, or making something that fits, that’s proportional to the area. We had no desire to build a 50-storey, monster building,” Dagenais said.

“But the process ends up costing hundreds of thousands of dollars and taking years in arguing to try to save or preserve three buildings that have a collective value of zero … The buildings can never be saved to the point where they are usable. They don’t house anyone, they don’t generate any income. They’re nuisance properties, the police visit lots of times, there’s lots of break-ins, there’s obviously a fire potential.

“And, yet, they just sit there as monuments — million-dollar monuments — and the private citizen bears all the costs and all the risk and all the liability to preserve things that generate no value.”

Dagenais said he was hesitant to propose another redevelopment project “because we would probably have to jump through 150 or 200 hoops.

“Not to say that we shouldn’t jump through any hoops, but the hoops should make sense. They should be logical, they should be practical, and they should be achievable.”

Église Unie St-Marc — 325 Elgin St.

Built in 1900, the St. Marc parish church at the intersection of Elgin and Lewis streets was considered the most significant house of worship for the city’s French protestants.

The congregation has since moved to a new church on Cumberland Street and the abandoned church suffered a partial collapse with its distinctive tower in 2021.

The city approved the dismantling of the tower and stabilization of the remaining structure and in 2023 entered into an easement agreement with the parish owning the building.

That agreement was not fulfilled, Collins told the committee in January, and the work was never undertaken.

The city provided notice in the fall of 2025 that the owner was in default of the easement agreement and that the city would undertake the stabilization work.

The first phase of that work commenced in December as crews moved structural supports off the city’s right-of-way and onto the property and built a temporary roof to prevent further weather damage to the remaining masonry of the tower.

Collins said staff were planning the next phase of stabilizing the remaining masonry, set for the spring. All the costs will be recovered from the property owner, Collins said.

“Restoring and rebuilding to its original condition would be a major undertaking,” said Hunter McGill of Heritage Ottawa. “And churches typically have limited resources, so, unless a government — whether that’s municipal or provincial — is willing to come through with a grant, the congregation is stuck.”

Sisters of the Visitation convent — 114 Richmond Rd.

The 19th century convent at 114 Richmond Rd. is one of the derelict properties on the city’s heritage watchlist that is “trending in the right direction,” Collins told the committee.

The historic convent just west of Island Park Drive was purchased in 1910 by the secluded and cloistered order of nuns, Sisters of the Visitation of Holy Mary, who resided in the three-storey stone villa and monastery until 2008.

The convent was listed for sale in 2009 and was purchased by Ashcroft Homes, while community groups fought to preserve its heritage designation.

The building was among the Ashcroft-owned homes that were listed for sale last year and has since been purchased by a new owner, Collins told the built heritage committee.

The owner has engaged an engineer to review the building condition “and is working collaboratively with heritage planning staff and building code services staff,” Collins said.

Heritage planning staff are anticipating a new development proposal for the site sometime this year that will be presented to the committee for approval.

Kitchissippi Coun. Jeff Leiper, one of the committee members who has pushed for more legislative “teeth” — along with Troster and Rideau-Vanier Coun. Stephanie Plante — says he is optimistic the new owner will move forward with a “heritage-sensitive development within some foreseeable timeframe.”

Magee House — 1119 Wellington St. W.

Leiper was less than optimistic about another building in his ward, the historic Magee House at 1119 Wellington St. W., which

has been sitting vacant — and somewhat precarious — since its southeast wall collapsed in 2018.

Collins said the building, one of the oldest in the city and considered a cornerstone of the earliest days of Hintonburg, was being “actively monitored” for further structural damage.

The building is not expected to survive beyond the next winter, according to deputy chief building official Scott Lockhart.

“I get relatively frequent notes from residents who are concerned that they’re seeing new bulges, new cracks, etc.,” Leiper said. “When I pass by, I share their concerns at times.”

Lockhart said the city had engaged third-party engineers who were continuously monitoring the building.

An engineering study in the fall of 2025 indicated the building was secure for this winter, “but they didn’t expect the building to survive more than this upcoming winter,” Lockhart said.

Building code services staff recently compared photos submitted from concerned residents depicting cracks in the mortar and staff “confirmed that there was no additional movement,” Lockhart said.

The engineering team is expected to revisit the site in the spring and will make further recommendations for demolition or further stabilization.

Engineers have taken measurements of some of the failures in the mortar, particularly in the lower corner along the front facade near the point of the original collapse.

“There is dry-stack stone in that building, so often it’s an aesthetic mortar that’s falling out, but it’s not one that’s affecting the building structure,” Lockhart said.

Leiper expressed his frustration in dealing with a “recalcitrant” building owner.

“I don’t know the degree of success we might have in trying to push them to redevelop this property,” Leiper said. “But I appreciate the efforts to at least make sure that the community is safe.”

Related

- Why so many Ottawa heritage buildings sit empty and decaying

- Lowertown heritage buildings approved for demolition by committee

Our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark our homepage and sign up for our newsletters so we can keep you informed.