‘We are in a generational-level crisis and governments aren’t treating it like one.’

Soaring costs, ever-changing rules, bureaucratic delays and development charges that are really a disguised wealth transfer from millennials to baby boomers are all making Ontario’s “generational” housing crisis worse, according to a new report on the plight of the development industry.

The Survive 2025: Perspectives on a Sector on the Edge report by the consultant group StrategyCorp surveyed 21 executives in the province’s house-building industry. It’s a glimpse into what life is like for property developers, a profession that usually dwells somewhere around lawyers and politicians in popular opinion.

THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Exclusive articles from Elizabeth Payne, David Pugliese, Andrew Duffy, Bruce Deachman and others. Plus, food reviews and event listings in the weekly newsletter, Ottawa, Out of Office.

- Unlimited online access to Ottawa Citizen and 15 news sites with one account.

- Ottawa Citizen ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles, including the New York Times Crossword.

- Support local journalism.

SUBSCRIBE TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Exclusive articles from Elizabeth Payne, David Pugliese, Andrew Duffy, Bruce Deachman and others. Plus, food reviews and event listings in the weekly newsletter, Ottawa, Out of Office.

- Unlimited online access to Ottawa Citizen and 15 news sites with one account.

- Ottawa Citizen ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles, including the New York Times Crossword.

- Support local journalism.

REGISTER / SIGN IN TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

THIS ARTICLE IS FREE TO READ REGISTER TO UNLOCK.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments

- Enjoy additional articles per month

- Get email updates from your favourite authors

Sign In or Create an Account

or

“There’s the caricature of greedy developers sitting on a hoard of cash,” said Aidan Grove-White, a principal at StrategyCorp. “People think that (developers) have everything they can possibly need and don’t require any sympathy.”

While that may be true for some high-rollers, that’s not the case for the majority, Grove-White said.

“I was also surprised at just how personal it was for many of them. They feel like they’ve been tasked with a really socially important goal and they’re not being given the tools or resources, or even, at times, the empathy from decision makers that they need to get there. They view themselves as community builders — as city builders.”

But, despite the urgent need for housing and the rising costs that are putting the dream of home ownership out of reach for so many, the homebuilders say they feel abandoned by government.

“We are in a generational-level crisis and governments aren’t treating it like one,” the report says.

“I was surprised at just how pessimistic the sector is about meeting its targets,” Grove-White said. “Each year that goes by without meeting our targets is a year that we have to add even more in the future. It’s like any other deficit. It means you’ll have to pay more later.”

Evening Update

The Ottawa Citizen’s best journalism, delivered directly to your inbox by 7 p.m. on weekdays.

By signing up you consent to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc.

Thanks for signing up!

A welcome email is on its way. If you don’t see it, please check your junk folder.

The next issue of Evening Update will soon be in your inbox.

We encountered an issue signing you up. Please try again

Private developers build about 90 per cent of all the new homes in the province and yet municipal governments tend to treat them shabbily, according to Grove-White, who says he supports the NDP and is not a shill for the development industry.

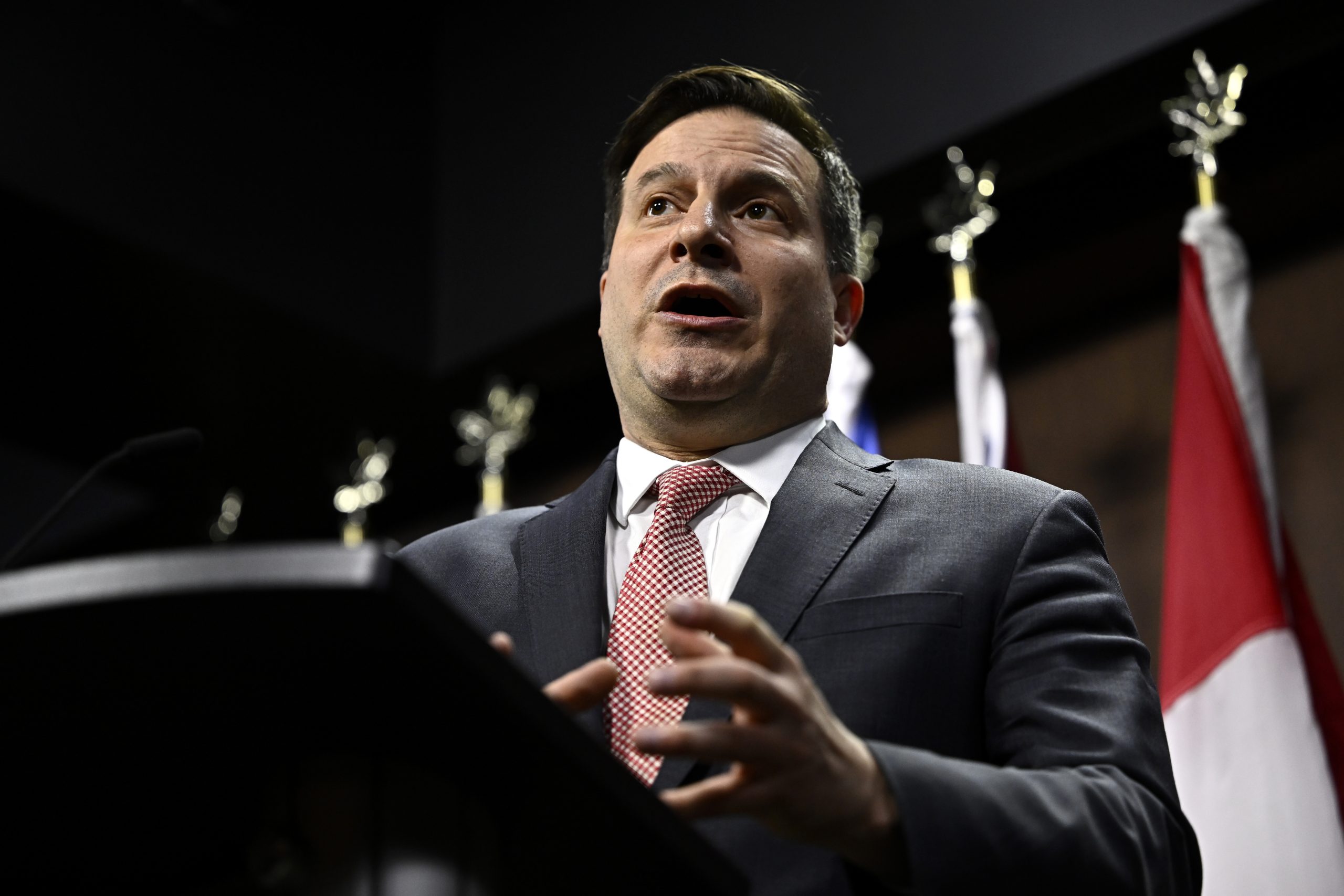

Ottawa has committed to building 151,000 new homes in the next decade and the city is nowhere near reaching that goal, said Jason Burggraaf, executive director of the Greater Ottawa Homebuilders Association.

“We’re still not near where we need to be,” Burggraaf said. “Our target is 15,000 homes a year, and we’re going to struggle to reach 10,000 (in 2024) and we will struggle to hit 10,000 again next year.”

One problem is the excessive red tape that slows construction. A simple project might take six to 12 months to get approval, Burggraaf said. A highrise tower? Years.

“With a subdivision, it’s easily eight, nine, 10 years before you get that on stream,” he said.

“You put in your application, it gets circulated to various departments and you put in your answers. And then you get another circulation and another round of questions. You’re constantly having to revise and being given new hoops to jump through. You’re constantly having to address and re-address planning rationales and saying it in different ways for different groups.”

Construction delays are one problem. Another is the ever-increasing costs of permits and municipalities’ reliance on development charges to fund infrastructure. Since 1997, Ontario municipalities have been allowed to apply development charges to new builds. That “growth pays for growth” concept means developers have to pay for sewers, water mains and other infrastructure costs on their own, rather than them being borne by municipalities.

One developer interviewed for the StrategyCorp report said development charges unfairly penalized new home buyers.

“I believe that development charges are an intergenerational wealth transfer from Millennials to Boomers and it needs to be undone,” he said (all respondents are anonymous in the report). “Every Boomer who bought a house didn’t pay DCs. Every Millennial has to pay them.”

In reality, although the developer has to pay that cost up front, the development charges are simply passed on to the consumer, raising the price of a new home by tens of thousands of dollars or more. Shifting that cost to new home buyers lets municipal politicians keep property taxes low for existing owners. But is that fair?

“We’re generally supportive of the concept of ‘growth pays for growth,’” Burggraaf said, but Ottawa’s development charges are among the highest in Ontario and keep going up. The city has also tacked the cost of some very specialized projects into development charges.

Anyone who buys a new home or condo — or is even a tenant in a newly built rental unit — will be paying toward a proposed Olympic-sized pool in the city. While the project itself is good for Ottawa, its cost shouldn’t be on the backs of new home buyers, Burggraaf said.

“To me, that’s a very difficult project to justify. It’s a very specific use.”

Similarly, borrowing charges on the cost of the Confederation Line LRT are lumped into new development charges, he said.

“It’s rich that someone buying a new home five or six years from now is paying the borrowing cost on Stage 1 LRT that’s already been running for five years,” Burggraaf said. “How is that not a communal good that should be paid by everyone when instead it’s all on the backs of new people who are just trying to join the housing market?”

It’s the first time StrategyCorp has polled developers about their industry; it usually does annual surveys of municipal chief operating officers. The company wasn’t paid for the survey and Grove-White, an NDP member, says he isn’t a lobbyist for the home-building industry. He described the report as more of a “curiosity exercise.”

Echoing Mayor Mark Sutcliffe’s “Fairness for Ottawa” campaign, Grove-White says the federal and provincial governments have to step up and do more to help municipalities tackle the province’s housing shortage. A little sympathy would help, too, he said.

“If there’s one takeaway, it’s this: Developers are not the enemy. They want to build. That’s their life ambition, to build a lot of homes. That’s something I’d like to come out of this: a little bit more empathy from politicians from all sorts of backgrounds.

“Developers are people. You cut them, they bleed. If we can be a little bit more empathetic and see them as partners in solving this problem, that would be mission accomplished for me.”

Share this article in your social network