Philippe Hébert will serve no time in prison following his guilty plea to manslaughter in the

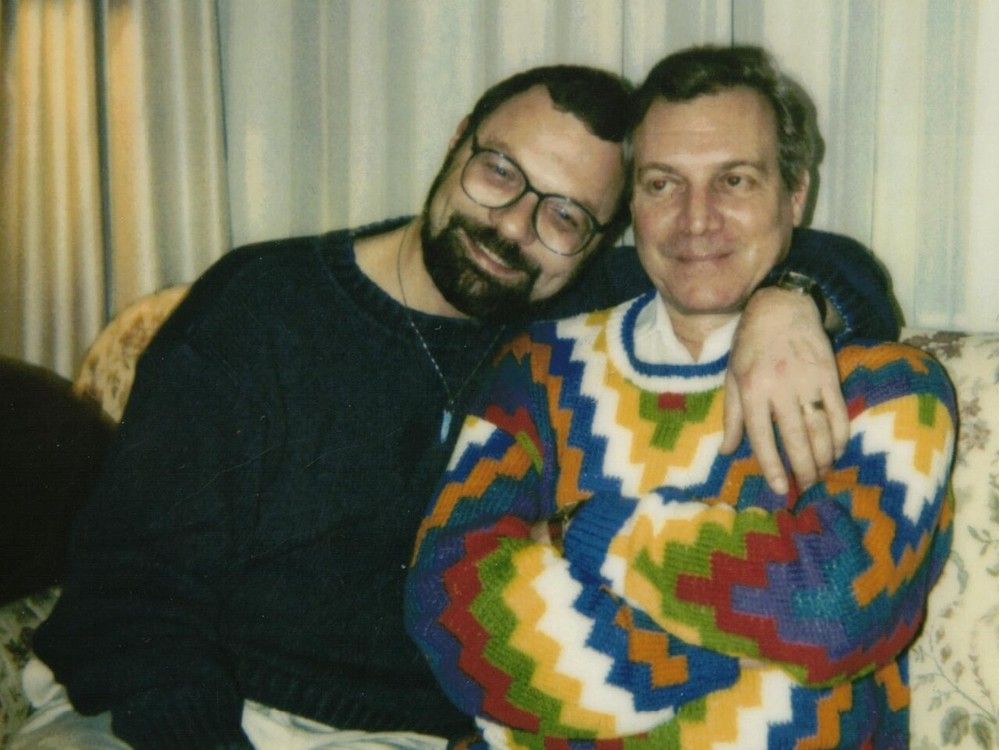

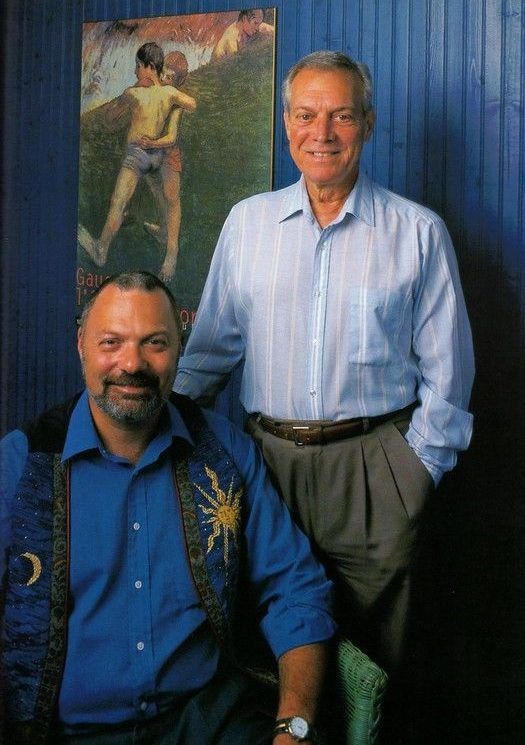

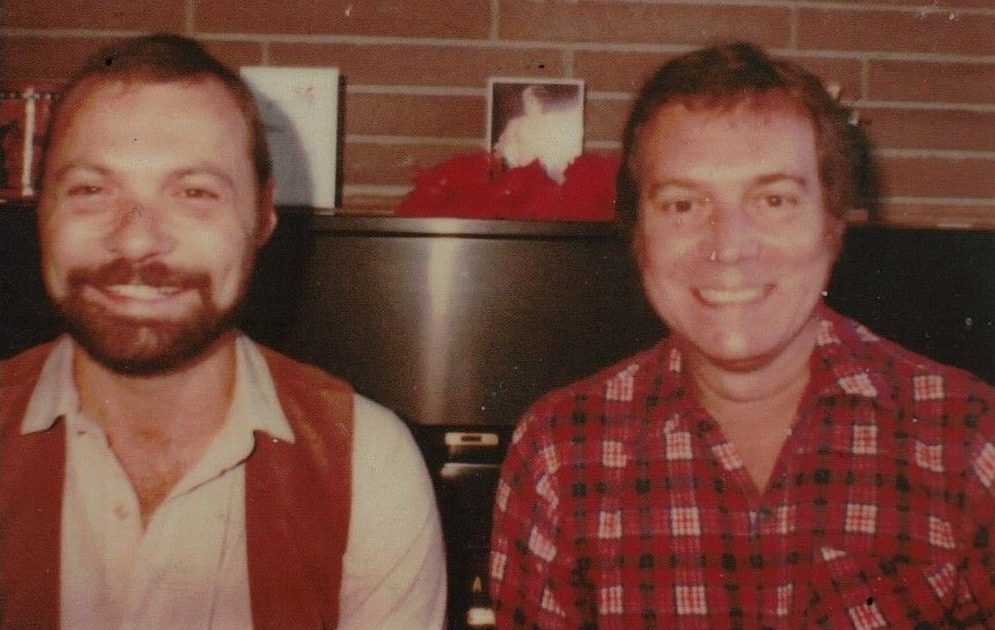

homicide of his husband and partner

for over 40 years, Richard Rutherford, a judge has ruled.

Superior Court Justice Kevin Phillips sentenced Hébert, 73, to two years less a day, to be served under house arrest at the home Hébert shared for decades with Rutherford in Ottawa’s east end.

The conditional sentence was less than the two years Hébert’s own lawyer, Solomon Friedman, had asked for during the defence’s sentencing submissions earlier this year.

The Crown had asked for six years in prison.

“Don’t let me down, sir,” Justice Phillips told Hébert, who had approached the bench and stood directly before the judge after having difficulty hearing him explain the terms of his house arrest.

Hébert had already spent what the court deemed equivalent to 38 days in pre-trial custody.

“This is a very challenging sentencing,” the judge told a courtroom packed with Hébert’s supporters, many of whom wiped away tears as it became clear that he would not be incarcerated.

“On the one hand, it is difficult to comprehend that a man can unlawfully take another man’s life and not go to jail,” the judge went on to say before citing a litany of mitigating factors in the case, including that

Rutherford had asked Hébert to end his life

, that Hébert was suffering from caregiver burnout after years of ministering to his ailing husband, and that Hébert was depressed and in the early stages of dementia when he agreed to the “mercy killing.”

Rutherford was a former principal dancer with the

Royal Winnipeg Ballet

, and

from the 1980s the home he shared

with Hébert on Smyth Road became a hub for Ottawa’s gay and arts communities.

Hébert worked for many years as a physiotherapy assistant at The Ottawa Hospital Rehabilitation Centre.

The pair wed in 2006, less than a year following the legalization of same-sex marriage.

“I’ve travelled all over the world, from Flin Flon to Moscow,” Rutherford told a care coordinator with the local agency in charge of delivering home and community-care services in the hours before he died.

“But the greatest part of my life has been living with Philippe.”

The homicide took place in April 2022, during the tail end of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rutherford, 87, was suffering from a host of medical conditions, including prostate cancer, vascular dementia and diabetes, and was spending upwards of 20 hours a day in bed.

The care coordinator had just deemed Rutherford incapable of deciding for himself whether to enter long-term care.

Justice Phillips described the coordinator’s visit as “something of call for help,” adding:

“Mr. Rutherford was ailing and Mr. Hébert was exhausted. He had been managing a gruelling caregiving load. He kept the house, prepared the meals and assisted with Mr. Rutherford’s personal hygiene needs.”

It was likely in the early hours of Easter Friday that Hébert awoke to find Rutherford crying in bed beside him.

“He told me that he could not go on, that he was ready to die and that he wanted me to help him end his life,” Hébert said in an affidavit filed with the court and read aloud by the judge.

“I told him that I did not know if I could do it.”

It was not the first time Rutherford had expressed a desire to die rather than enter long-term care.

Hébert agreed to do as Rutherford asked and said he would end his own life after ending his.

“I used an incontinence pad to suffocate Mr. Rutherford, holding it in place until I was certain that he had died,” Hébert said in the affidavit.

“In the end I honoured the last wish of my husband and best friend.”

After attempting various methods to die by suicide, Hébert eventually called 911 and explained what he had done.

He was later charged with second-degree murder.

Hébert’s guilty plea to manslaughter in September followed an agreement and a joint statement of facts between the defence and the Crown on what would have been the eve of his trial.

During sentencing submissions in September and January, Friedman argued that over the last two decades judges presiding over so-called “mercy killing” cases had most often handed down conditional sentences such as the one ultimately imposed in the Hébert matter.

But Friedman and Crowns John Semenoff and Elena Davies could not come to terms on the length of sentence.

That disagreement and the wide latitude permitted in manslaughter sentences allowed Justice Phillips to make his own determination.

“In every respect, this was an assisted-suicide mercy killing,” the judge said during sentencing.

Though Rutherford had been deemed incapable, Justice Phillips took pains to explain why in his view Rutherford still had the capacity to ask for Hébert’s help in ending his life.

“The full constellation of evidence before me shows that Mr. Rutherford had a form of distorted perception about his care needs, which distortion came from the fact that Mr. Hébert was continuously solving all of the care-related problems in a way that, while unsustainable, was nonetheless quietly effective,” Justice Phillips said.

“Mr. Hébert was like a constantly available yet invisible helping hand that allowed Mr. Rutherford to believe that he did not need him.”

Justice Phillips concluded this area of his decision by adding:

“Mr. Rutherford could not see what was there to see — that they needed outside help. At the same time the overall evidence shows that at all material times Mr. Rutherford had his wits about him enough to make fully rational decisions in a general way.”

In large part due to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hébert was under “a mistaken belief that there were no other options, as he did not think [Medical Assistance in Dying] was possible and a care facility was a couple of years waiting,” the judge said.

“Also, in my judgement, his level of dangerousness to the general public is basically zero. Mr. Hébert poses no threat or risk to anyone.

“He has gained nothing from this crime, only loss.”

Justice Phillips also pointed out the burdens of house arrest.

Hébert will be permitted to leave the property only for medical appointments and for three hours each week to purchase groceries and other necessities. He is also prohibited from consuming alcohol.

“The reality is that there is no punishment that I could impose that will be harder on Mr. Hébert than living with Mr. Rutherford’s death,” said the judge.

Later, outside the Ottawa courthouse on Elgin Street, Hébert stood beside Friedman before a crowd of his supporters, many of them part of a needlepoint group of which Hébert is also a member.

Under his coat Hébert wore one of the colourfully embroidered vests that have been his signature in court and which he makes himself.

Opting not to speak, he nodded along as Friedman delivered a statement:

“I have never been in a courtroom and felt so much love for my client,” Friedman said.

Related

- ‘I would rather die’: How a decades-long love affair ended with homicide

- The ‘tragic and profoundly human’ story of Richard Rutherford and Philippe Hébert