When Forrest Pass, curator for Library and Archives Canada (LAC), first dug into the history of Filipinos in Canada, he was only expecting to find some isolated or unusual cases of individuals migrating from the Philippines.

But listed among early 20th-century log records that accompanied the Canadian Pacific steamship services between Victoria, B.C., and Manila, Philippines, Pass says, were glimpses of the lives of people who lived at that time, including the first dozen recorded Filipinos in Canada.

“Certainly, we know about the migration that began in the 1960s and the vibrant community that exists today,” he says. “But to look for some of the antecedents, to look for some of the earliest Filipino settlers in Canada. I wasn’t expecting to find as much as I did.”

How the project started

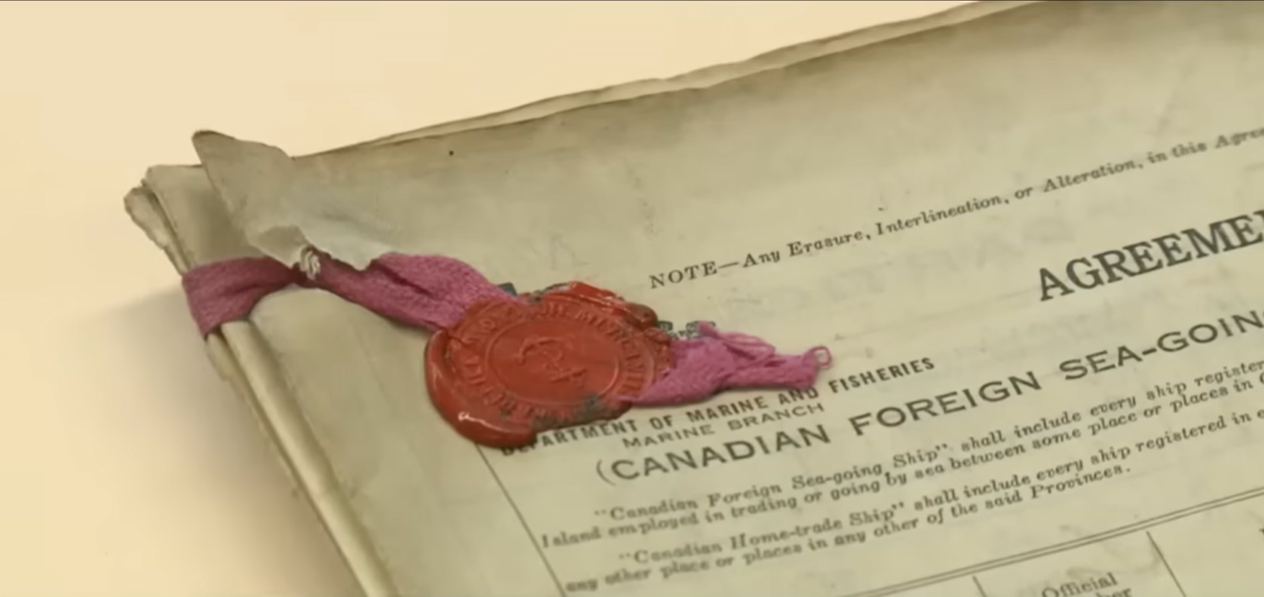

Wearing blue gloves, Pass carefully held the old ship manifests with both hands from its box and placed them onto the table. Its corners are darkened, wrinkled, and the pages are bound by what looks like a pink ribbon at the top left, stamped with a striking, chipped red seal.

“This seal right here is the harbour service of Hong Kong indicating that the log had been sealed for inspection there,” he says, pointing at the red seal, adding these logs were kept by captains or officers of the Canadian Pacific steamships Empress of Russia and Empress of Asia, two of the transpacific passenger ships that travel between Vancouver and Manila via China, Japan, and Hong Kong in the 1930s.

Flipping through the papers, Pass paused at the page with various purple, green and red stamps pointing to the stamp at the bottom-left corner. “Here you see the British Consulate General in Manila, the date of arrival, 1931.”

For many, it may be old log records; but for Pass, it offers a glimpse into the lives of Canadians in the early 20th century and the lesser-known history of Filipinos in Canada.

In 1931, a man born in Manila travelled aboard these ships to visit his father’s cousin in Toronto.

In 1933, a Filipino lawyer visited Banff on vacation.

In 1929, a Pentecostal missionary returned to London, Ont. from the Philippines.

“This was a greater adventure than it would be today whether for Canadian tourists to the Philippines or Filipino immigrants to come to Canada,” he says.

Intrigued by the hints, Pass dug through the archives and available censuses as early as 1901.

The first Filipinos on record

Twelve people of Filipino descent were recorded in the 1901 census data, according to Library and Archives Canada.

One iron moulder named Mariano Gomez was recorded in Merrickville, Ont. He was, according to the agency, the only Filipino in the province at the time.

Eleven were in B.C.: four people in Vancouver, and seven fishermen were on Bowen Island, including Fernando and Mary Toreenya, who came to Canada in 1881.

“There were a number of Filipino labourers I found in Vancouver, and that’s to be expected. This was a major Pacific port,” says Pass. “What I wasn’t expecting was a small community in Bowen Island, a little way away from Vancouver, it’s a bit out of town even today.”

“We don’t necessarily think of immigration to small-town Canada in the early part of the 20th century, and yet here we find a Filipino community in a very, very remote part of B.C… One wonders how they ended up there, how the first settler arrived in Bowen Island, and what convinced him to encourage others to come and join him,” the historian adds.

In 2024, the City of Vancouver declared April 11 as Benson Flores Day, commemorating the man who is believed to be the first known Filipino settler, 95 years after his passing.

Benson Flores was a fisherman, a beachcomber, and the owner of a boat rental business on the island. He came to British Columbia in 1861, 10 years before the province became part of Canada.

The United Filipino Canadian Associations in B.C. (UFCABC) says these findings bring pride to Canada’s Filipino community.

“It is the first time we’ve seen Filipinos on record,” says Clifford Belgica, UFCABC’s program director. “Before this information came out, we were told the first wave of Filipinos were in the 1930s, you know, tannery workers, and then the 50s, the nurses and so on. But now we’re moving forward.”

Transcription errors, language barriers affect accuracy

According to Statistics Canada, censuses began asking about an individual’s birthplace, citizenship, and period of immigration as of 1901.

“The historical census data were always a challenge because the quality of records is only as good as the enumerators who filled out the forms,” says Pass, pointing to the fact that enumerators typically spoke only English and French. “They wouldn’t have been familiar with Tagalog spelling or names, so we find names that are transcribed in unusual ways.”

Other challenges include the digitization of census records and how individuals were identified.

“The optical character recognition systems used to transcribe these records aren’t perfect,” Pass says. “One family in Quebec City were identified in the index as from the Philippines, but in the original records, they are in fact from Philadelphia.”

“This was simply a transcription error either in part of human or software system.”

Another challenge, according to the historian, is how the individuals were identified.

“One Filipino settler whom I found in Merrickville (Ont.) is identified as being born in the Philippines and being ethnically Filipino. In another census, he’s identified as from Brazil,” Pass says.

“I wonder if it’s a question of a language barrier or the sloppiness of the enumerator not taking the time to determine where this person is from.”

20th-century tourism and early Filipino-American experiences in Canada

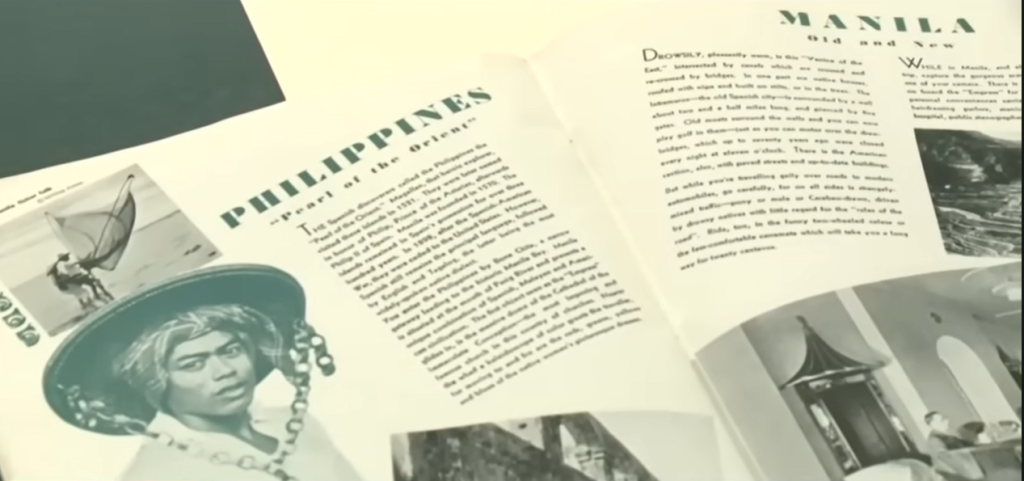

Pass points to a 1934 tourism brochure marketing Asia to Canadian tourists, promoting Canadian Pacific steamship travels through countries such as Japan and China, with its last stop at the Philippines, advertised as the “Pearl of the Orient.”

But among those boarding these steamships in Asia are Filipino migrants travelling to the U.S. through Canada.

“Their first experience in North America would’ve been landing in Victoria,” says Pass. “Their first sight of North America would’ve been Vancouver Island or Victoria.”

Highlighting early Canada-Philippines ties

In a statement to OMNI News, the Philippine Embassy in Canada extends its appreciation to LAC for uncovering the historical records, saying, “these findings enrich our understanding of the deep roots and long-standing contributions of the Filipino diaspora to Canadian society, and serve as a reminder that Filipino migration to Canada began earlier than widely recognized.”

“We continue to invite institutions such as Statistics Canada and other academic researchers to build on LAC’s work and further explore and document the migration history of Filipinos in Canada,” the embassy adds.

“This is in the hope of strengthening the bonds between the Philippines and Canada and inspiring the next generation of Filipino-Canadians to take pride in their heritage.”

Making the past visible and accessible

For those interested in searching their family history, Canada’s census returns have been digitized and are searchable from 1825 to 1931, as well as immigration records, including passenger lists, through the Library and Archives Canada’s Genealogy and Family History webpage.

“When people think about the collection of LAC, the things that might come to mind are the proclamation of the constitution,” Pass says. “But there are also stories of communities that can be teased out of census records, passenger records, small mentions in government correspondence that might otherwise be lost.”

Pass says through the record, it’s important to remember that Canada has always been a multicultural country and that there are traces of vibrant communities from different parts of the world settling at an early date.