With “Frankenstein,” monster maestro Guillermo del Toro finally gets to tell the Mary Shelley horror story of his boyhood dreams.

The Toronto-filmed epic is a thing of grotesque beauty, body horror of such operatic spectacle and emotional impact, it makes you want to applaud with two severed hands.

A teenage Shelley wrote in the preface to her 1818 novel that her tale of a lonely humanoid pieced together from stolen corpses is more than “merely weaving a series of supernatural terrors.”

Indeed it is, much more. Del Toro asked the question posed by the author’s prose at Monday’s official North American premiere of “Frankenstein” at the Toronto International Film Festival. The sold-out event, attended by Mayor Olivia Chow, was such a hot ticket that the rush line stretched for blocks outside the Princess of Wales Theatre.

“What does it mean to be human in a time of inhumanity, war and in a moment of doubt as a race?” del Toro said. “That was true back then, and it’s true right now.”

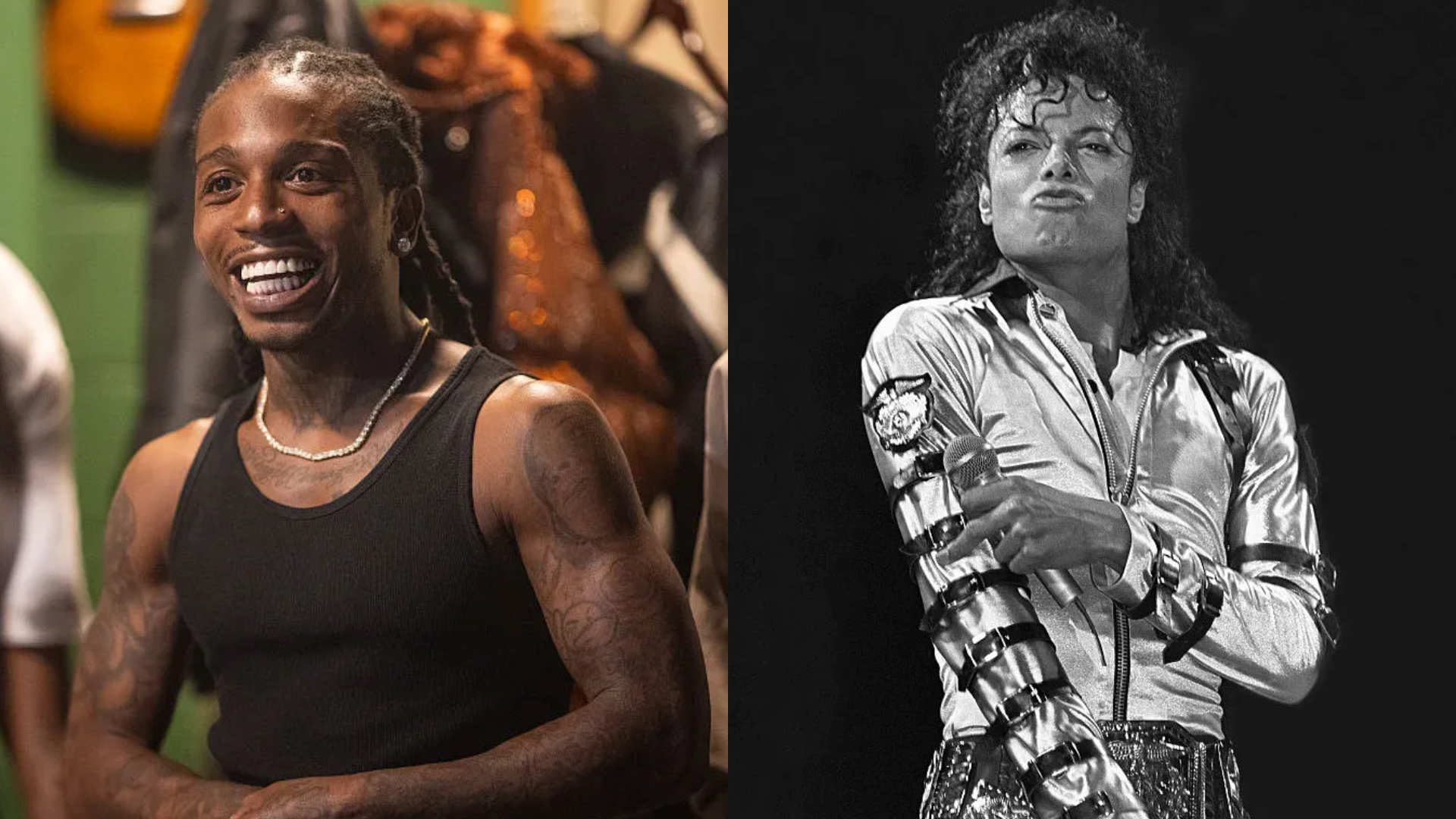

With Jacob Elordi and Oscar Isaac, the Academy Award-winning writer-director (“The Shape of Water”) has found the ideal duo to explore Shelley’s classic query in all its grisly glory.

Aussie actor Elordi makes a studly Creature, one of the most virile and emotive specimens to stalk a Frankensteinian stage that has seen everyone from Brigitte Helm to Boris Karloff to Emma Stone play versions of the patchwork monster. Elordi’s contemplative and mummy-like Creature resembles the life-giving Engineers of the “Alien” saga, an intriguing inversion since he’s the one being brought to life by a human.

Isaac plays the arrogant scientist Victor Frankenstein, who, in literary terms, is a cross between Emily Brontë’s brutal romanticist, Heathcliff, and Joseph Conrad’s colonial overlord, Mr. Kurtz.

Del Toro’s trusted team of craftspeople pull out all the stops for a movie the 60-year Mexican filmmaker has wanted to make since he was old enough to read.

Cinematographer Dan Laustsen uses wide-angle lenses that sometimes slightly distort, imparting a mood that calls to mind both the funhouse and charnel house. Other inspired collaborators are production designer Tamara Deverell, who nods to previous del Toro works with her sci-fi-infused handmade sets; costume designer Kate Hawley, who turns horror queen Mia Goth into a showstopping peacock; and composer Alexandre Desplat, whose thunderous score turns joyous in the oddest moments, enhancing the sensation of “Alice in Wonderland” unreality.

Largely faithful to Shelley’s text, del Toro retains the 19th-century setting, bookending “Frankenstein” with Arctic confrontations and a back story told to an icebound and spellbound sea captain (Lars Mikkelsen). But del Toro splits the main story into chapters headed “Victor’s Tale” and “The Creature’s Tale.”

“Victor’s Tale” hews a tad too closely to Shelley’s ornate prose as it laboriously establishes Victor’s tragic early days as a motherless child (Christian Convery) raised by an unfeeling father (Charles Dance).

Victor grows to become a cocky and recklessly curious scientist, whose experiments with reanimating dead body parts shocks and outrages members of the Royal College of Medicine. But he greatly interests sleazy arms dealer Heinrich Harlander (Christoph Waltz), who agrees to fund Victor’s research in exchange for an unspecified future “favour” that sounds like something out of “The Godfather” but would make Don Corleone recoil in disgust.

There’s also a love interest: Goth’s forthright Elizabeth. She’s engaged to Victor’s milder younger brother, William (Felix Kammerer), but can’t fight her attraction to the scientist who wants to play God.

Victor does just that in the film’s energizing second half, when he stitches together the Creature from the parts of dead soldiers he’s filched from a battlefield. Victor’s “Eureka!” moment, when he learns how to reanimate dead flesh, shows him stark naked, having leapt out of the bathtub to test his theory. (Del Toro calls this process a “waltz” rather than the traditional Hollywood electrical jolt.)

Unlike in most “Frankenstein” sagas, here the newly awakened Creature doesn’t immediately burst from the lab and threaten terrified villagers. Del Toro provides some getting-to-know-you moments first, including a touching scene in which Victor introduces the Creature to sunlight. His reference to “sun” makes it sound like he’s embracing his new “son.”

Elordi’s Creature basks in the attention like a rapidly growing toddler, discovering the world and seeking to find love and kinship in it. But selfish Victor soon tires of his creation and abandons him — calling him “it” — leaving the Creature to begin a confused, angry and violent exploration of a world he now despises.

Even worse, the Creature is condemned to live forever in his misery; his stolen flesh immediately regrows after assaults by fire, bullets and knives. And Victor similarly doesn’t escape torment, having to live with the tragic result of his attempt to be a deity.

As the Creature wanders forlornly, searching for Victor and some kind of release, the monster discovers a blind old man who befriends him, offering food and simple companionship.

“What are you afraid of?” the man asks.

“Everything!” the Creature replies.

He could take solace in knowing del Toro has given us everything we could want in a Frankenstein movie, blending showmanship with soulfulness.

It’s a fine time at the movies for lovers of vivid nightmares.