Simply defined, “diopters” is the pluralized form of a measure of reflective power in an optical lens. It’s not a word in everyone’s mental lexicon, but if you play your tiles right, it can earn you 149 points on the world’s biggest

Scrabble

stage

.

And that’s exactly what Ottawa mathematician Adam Logan did, as he placed the letters across two triple-word squares in his highest-scoring play of the World Scrabble Championship.

In two turns alone, Logan had added a whopping 252 points to his score — “infamies” had been his previous move for an impressive 103 points — to erase his opponent’s lead and complete a major comeback in the third game of the

best-of-seven matchup of the World Scrabble Championship

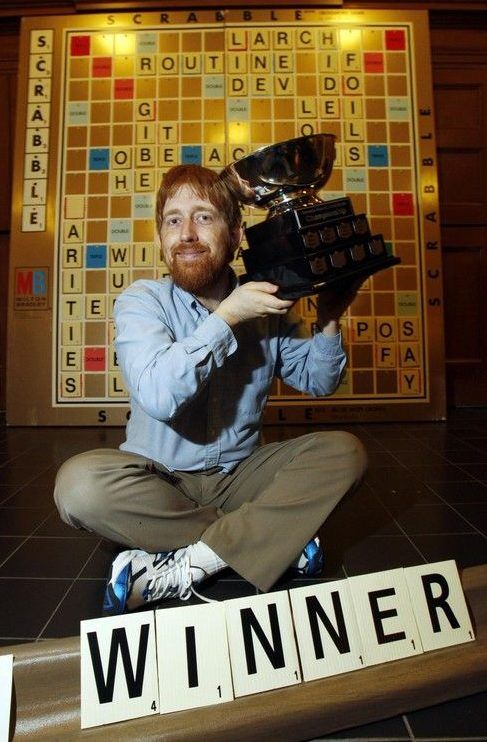

final in Accra, Ghana. Logan went on to win game three, and then, hours later, the championship title by a score of four games to two.

It was a long journey since he picked up his first Scrabble strategy book from a dusty corner of a Quebec cottage at just nine years old. With the win, Logan joins an elite group of Scrabble juggernauts (a word worth 20 points, not including any bonus scores), becoming only the third person in the world to win multiple World Scrabble Championship titles.

“I had to consciously tell myself to slow down. Look at it for a few seconds. Make sure that you’re spelling correctly,” said Logan while recalling the final moments leading up to his championship win.

It’s not exactly like the Canadian expected to emerge victorious. Sitting across the table was grizzled (28 points) veteran Nigel Richards — widely regarded as the best Scrabble player of all time with five world championship titles to his name. Richards has also won Scrabble championships in French and Spanish, despite the fact that he doesn’t speak either language.

And it’d been exactly 20 years since Logan won his first Scrabble championship in London, England, at the age of 30. Two decades later, it’s still a moment he looks back on in disbelief.

“It was something that I really couldn’t quite believe that I had done,” Logan said. “I somehow felt that I knew that in a single game, I could beat anyone, but it’s a long way from that to being able to be consistent, being able to even reasonably aspire to have enough luck to win that many games over a period of time. So it was really something exciting and wonderful for me.”

Logan describes Scrabble as a unique blend of strategy and luck — while you can’t control the tiles you pull out of the bag, you can optimize using bonus squares, balancing your rack and blocking your opponent’s best moves.

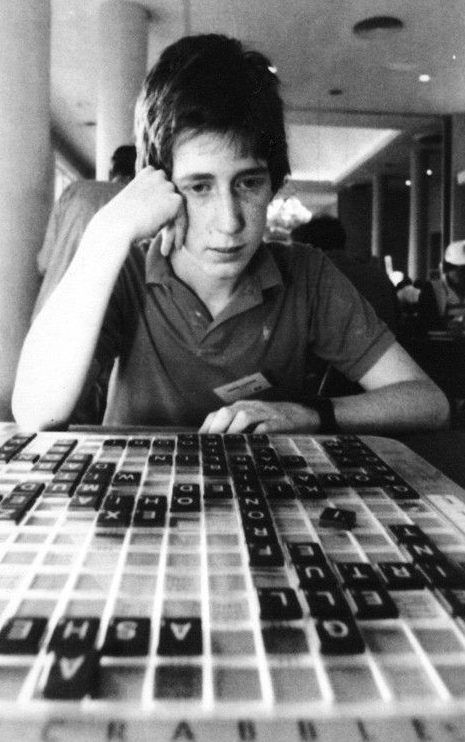

Logan first started familiarizing himself with these ins and outs at age 10, when he competed in his first Scrabble tournament in Ottawa in 1985.

A 10-year-old boy isn’t your typical Scrabble player — something the Ottawa tournament organizers were quick to point out when a young and spry Logan showed up to compete.

Logan’s mother, Michal Ben-Cera, recalls that the organizers would only let her son play under one condition: “They told me that if they ended up with an uneven number of players, they will take him, and that’s what happened,” Ben-Cera said. “And Adam came in the top four and went to Montreal to play in the next stage.”

Before he was even old enough to drive, Logan started travelling out of town to compete in Scrabble tournaments. He took home his first cash prize at a tournament in Montreal in 1987: a whopping $21 for placing second among 14 participants. He won his first tournament a year later in Montreal, taking home $60 for his efforts.

Now 50 years old, and a recent $10,000 US world championship cheque for his bank account, Logan’s

lifetime earnings come in at an estimated $110,000 US

— a solid career pay in the competitive Scrabble world, often built one $300 tournament win at a time.

Even before picking up the Scrabble strategy book, Logan’s parents knew their son possessed remarkable analytical capabilities. His father, George Logan, said his son was a calculating prodigy: he’d often find six-year-old Adam running around the house talking to himself as he quickly (25 points) multiplied complex equations in his head.

“He was always extremely interested in math,” his father said. “He liked to arrange things in patterns, and he didn’t just randomly play with blocks; he would always intentionally do something with them.”

Logan graduated high school at Lisgar Collegiate Institute in Ottawa and finished top of his class at Princeton studying mathematics.

From there, he went on to earn a PhD from Harvard in 1999. A succession of postdoctoral positions then led him to England from 2003 to 2005, which is when he was first introduced to the U.K. Scrabble dictionary — a larger and more complex version of its North American counterpart and commonly used in international competitions. Mastering this dictionary was the key to his first world championship win in 2005.

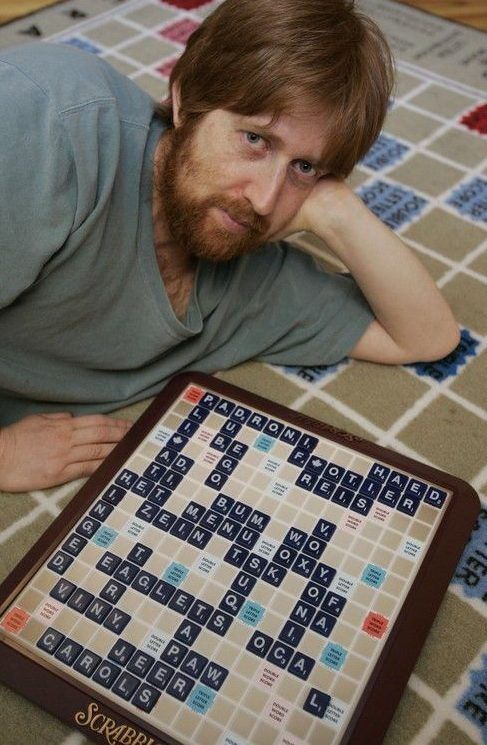

To keep his mind sharp for tournaments, he studies the Scrabble dictionary for as long as an hour a day using a spaced repetition method. He uses a computer program that shows him a series of letters in alphabetical order, which he must decode into a valid Scrabble word. With spaced repetition, the program reintroduces words at increasing intervals to reinforce long-term memory.

“By doing this, you can gain not only knowledge of what the words are, but also the ability to find them when you actually have tiles in front of you,” he said.

Scrabble and math may not appear to have much in common. But Logan said he’s able to maximize (28 points) similar analytical ways of thinking, including his knowledge of probability, to excel in both fields.

“I think there is something about being willing to absorb a lot of rather strange and arbitrary words that goes well with math,” he said.

Family across the world have been tuning in to watch Logan play, though it’s sometimes tougher to get a hold of him to chat in person. (Logan doesn’t own a cell phone.) His mother, who now lives in Israel, is one of his biggest cheerleaders. The two of them even met in Lisbon, Portugal and went hiking together before Logan continued to Ghana for the world championships.

Humble, never boastful and often his own worst critic, Logan’s mother says her son’s measure of success was never based on the scoreboard.

“He’s more concerned about his own judgment, about how well he played than about how successful he was in winning competitions,” she said. “He would analyze every game afterwards and feel really good if he felt he played well, even if he lost the game, and feel bad if he made mistakes, even if he won the game.”

Now living in Ottawa and continuing his research in mathematics, Logan doesn’t plan on giving up Scrabble anytime soon. With upcoming tournaments scheduled all over the world, there’s no shortage of opportunities for him to compete.

Aside from significantly expanding his vocabulary, he said the game of Scrabble has taught him a lot of meaningful lessons about being patient, taking risks and living life with utter quixotry (27 points).

“I feel somehow that in many ways, Scrabble does teach us a lot about life,” he said. “By whatever it may be, we can improve our lives by challenging ourselves and trying to do things that are just a little bit beyond our reach.”

Related

- Ottawa council to consider free transit for youths on evenings, weekends, holidays

- Joshua Clatney, advocate and leader for youth with addiction, dies at 28

Our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark our homepage and sign up for our newsletters so we can keep you informed.