Mark Monahan, the co-founder and executive director of Bluesfest, found himself at this year’s festival casting back a couple of decades to the event’s four-year stint at Ottawa City Hall.

The trigger? His first grandchild, 11-month-old Harley, was paying a visit.

The sight of a baby at Bluesfest brought Monahan back to the festival’s early days, when he and his wife, Reine, had a young family. At the time, their youngest (of four) daughters was about the same age as Harley.

Back then, Monahan used to rent a hot tub for his on-site trailer compound, and the kids loved it.

“We don’t have the hot tub anymore,” he said, smiling at the memory, and clearly delighted to welcome a third generation to the festival family. “But it feels like a full-circle moment.”

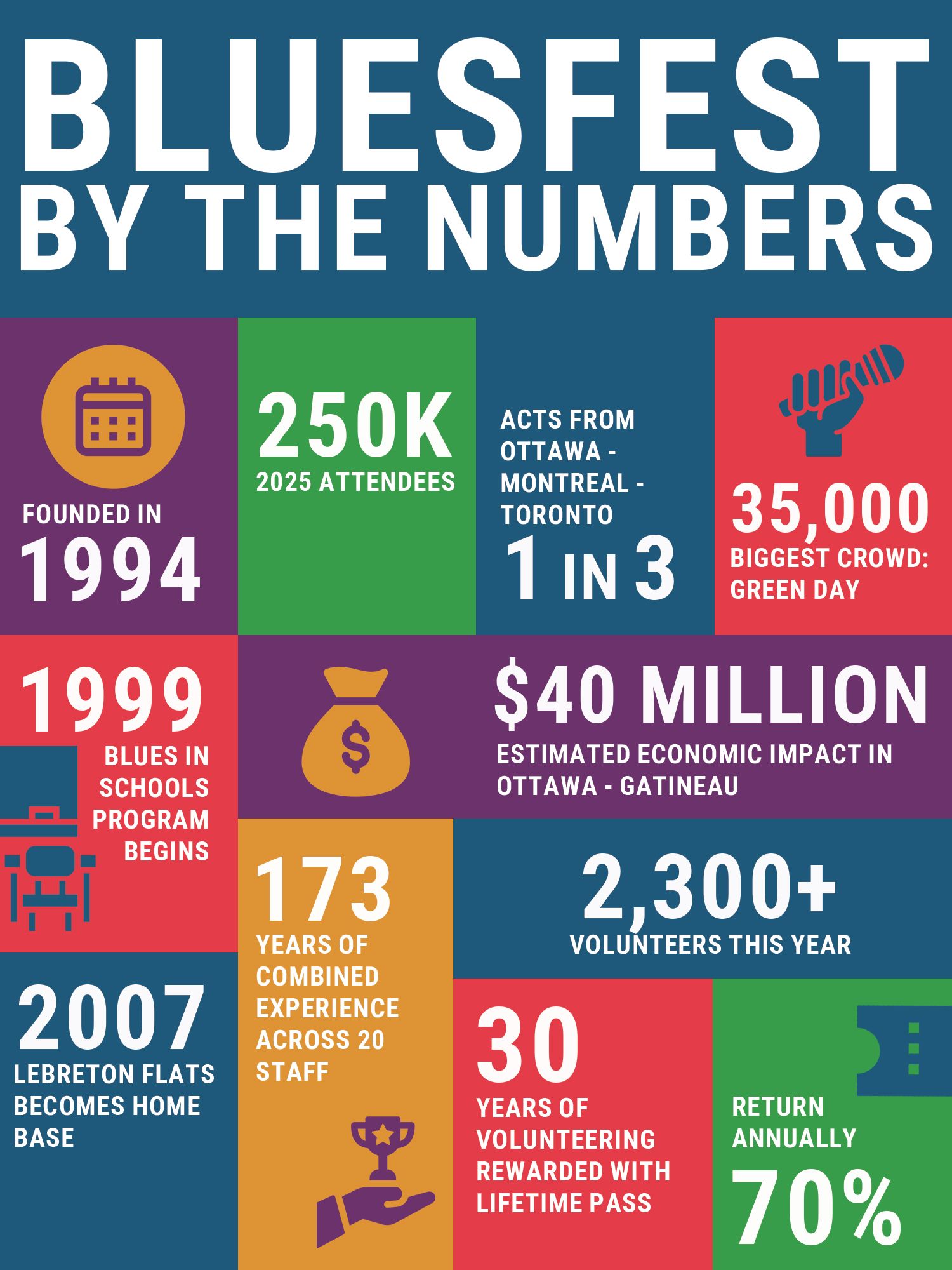

For three decades, Ottawa Bluesfest has taken over the city for two weeks in July, featuring major concerts on multiple stages and attracting tens of thousands of music fans of all ages.

It has grown into one of the biggest summer music festivals in the country, generating a buzz for being well-organized, multi-generational and diverse — with a picturesque location on the grounds of the Canadian War Museum at LeBreton Flats Park, next to the Ottawa River.

The biggest shows this year saw crowds of 30,000 or more turn up for Green Day, Lainey Wilson and Hozier, and total attendance is expected to surpass 250,000 visitors. With all those people spending money on restaurants, services and often hotels, the economic impact for Ottawa-Gatineau is estimated to be in the neighbourhood of $40 million.

But what is it about Ottawa that allowed Bluesfest to flourish? How did a government town come to host one of the biggest parties in the country?

The answer lies in the combination of timing, talent and a multi-pronged connection to the community.

When the festival started in 1994, nothing much happened in the city in July. Colleges and universities were on summer break, Parliament was adjourned, and many Ottawa-area residents flocked to their cottages.

The addition of a blues festival to the July calendar was a welcome development, and prompted a flurry of media coverage during the slow summer news period. The low ticket price encouraged the curious to take a chance, and within a few years, Bluesfest was bursting at the seams. It moved several times in the early years, from Major’s Hill Park to Confederation Park to city hall. It settled in its current location at LeBreton Flats Park in 2007.

As it grew, the festival dealt with some serious setbacks, including an ill-fated attempt to expand to other Ontario cities in 2005, the tragic stage collapse in 2011, and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2020 edition of the festival was called off because of the global health crisis, but a drive-in version of it took place that summer.

Through it all, the festival’s legions of volunteers remained its most steadfast supporters. The volunteer program started with 200 bodies in 1994; this year, volunteers numbered more than 2,300.

“Volunteers have always been some of our best ambassadors,” said Monahan, noting that about 70 per cent of them return year after year. One woman, Nicky Swift, was given an award last year to mark 30 years of Bluesfest volunteer service.

When asked why they keep coming back, several volunteers who crossed my path this summer told me they liked meeting people and seeing concerts for free.

Of course, Bluesfest is not free for most people to attend, but it’s worth knowing your ticket dollars have a purpose beyond the festival operations and talent budget. The festival is a non-profit charitable organization,

with a volunteer board of directors made up of local professionals and business owners from different walks of life.

Its mandate as a charity is to bring music education to children and youths through the Blues in the Schools and Be in the Band programs.

These programs not only help the festival cultivate new generations of live-music fans (and performers) but also build anticipation in the weeks leading up to the festival. Bluesfest’s last day is devoted to showcasing the kids’ hard work on the LeBreton stage, a finale that attracts dozens of family members and friends.

Another factor that differentiates Ottawa’s Bluesfest from other festivals is its commitment to local and regional artists. Monahan said a third of the acts on the program hail from the Montreal-Toronto-Ottawa triangle.

“They get treated like all the others,” Monahan said, “and we have great reviews from them about how happy they are to play on a big stage and be treated so well.”

Some of the homegrown highlights of this year’s festival were the flute-forward funk band, Funk Yo Self, Gatineau’s harmonious Leverage For Mountains, energetic pop-punk rockers We Were Sharks, the groovy duo of Dystoh and blues guitarist J.W.-Jones, who jumped in as a guest with a couple of other acts, too.

In addition to the musical ambassadors, connections are forged with local sponsors, suppliers and businesses like Wall Sound, an Ottawa company which has been handling the technical specs for years. Many hours went into positioning the screens and sound gear this year to improve the audio and visuals throughout the main plaza, especially at the street zone on the Kichi Zibi Mikan parkway.

And let’s not overlook the programming. While most people buy tickets based on the main-stage headliners, there are always some great shows on the side stages and in the opening slots. This year’s highlights included Father John Misty, the Decemberists and Men I Trust on the River stage, plus a terrific slate of blues programming on the LeBreton stage, along with intimate performances in the museum’s dark, air-conditioned Barney Danson Theatre.

“We’ve always got something for everyone,” said Monahan, “but this year was well-rounded, too.

“The level of attention to the whole lineup, from the regional acts to the mid-level to the side stages, is quite intense,” he added. “We spent a year on this. We’re not dropping something in and then doing another festival a month from now.”

Because the festival runs smoothly and treats artists well, it has a good reputation in the industry, with credit to the efforts of 20 full-time staff members working out of the Bluesfest office. To make it a year-round job, the team also organizes Ottawa’s CityFolk festival at Lansdowne Park in September, and the Festival of Small Halls.

“We have 173 years of collective experience just at this festival,” Monahan said. “We have all of these ties to the community, and all of us have raised our families here.”

Young Harley is testament to that, whether he grows up to be a volunteer, worker, musician or fan.

Related

- Here’s how local bands get the gig at Bluesfest

- How Sue Foley discovered the blues in Ottawa

We love where we live, and throughout the summer, we are running a series of stories that highlight what makes our community unique and special within Canada. Follow along with “How Canada Wins” right here.