Many First Nations across Canada struggle with crime, mental-health issues, drug abuse and trafficking.

But some communities in Manitoba are seeing a significant drop in crime and calls to health agencies, and they say it’s all because of how they’re letting the community lead.

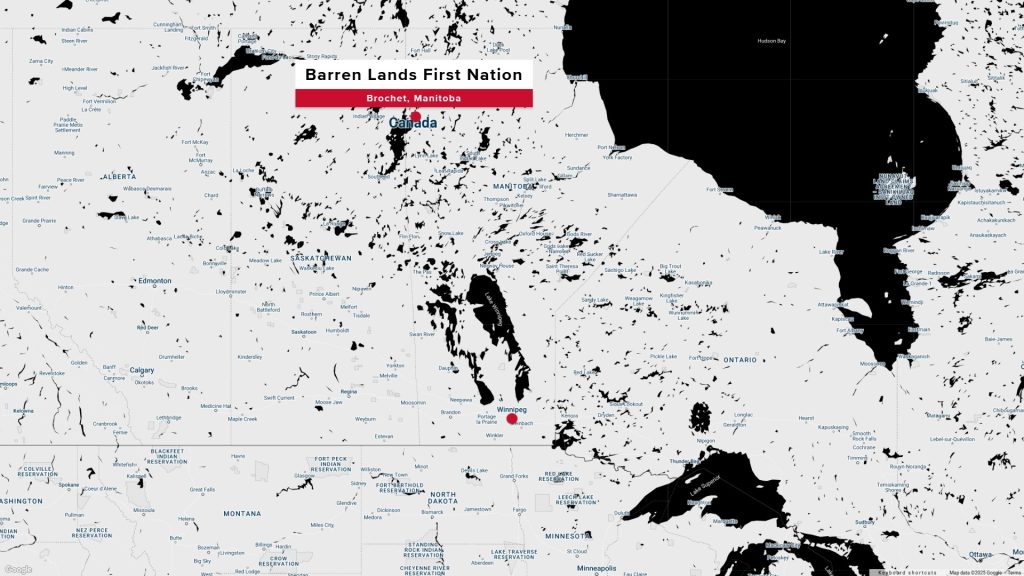

Chief Michael Sewap from Barren Lands First Nation – a community about 930 kilometres north of Winnipeg – says a big issue was people coming in and selling alcohol and drugs.

“There was so much drinking, so much drugs that have been brought in from outside members, and it was just basically getting worse. Worse and worse,” the chief said, adding everyone in the small community of fewer than 800 members was affected.

RELATED: Police crack down on ‘sophisticated’ Toronto organized crime group allegedly trafficking drugs, guns into Manitoba

Chief Sewap says what followed was a public meeting with the membership, including the mayor and council.

“Basically we asked for a vote, what to do regarding the bootleggers and the cocaine, meth dealers. Like what needs to be done,” he said.

And his community voted: they wanted outside help to tackle the problem on the ground.

That’s where Wayne Shuttleworth and the Anishinaabe PeaceKeepers come in.

“We just try to ensure the safety of everybody,” Shuttleworth explained. “We go to schools, we do school talks – well, I do. We try to engage with the community as much as possible, we’re at all sorts of festivals.

“When we come to community, we try to do as much as we can. From getting rid of meth and fentanyl dealers to eliminating the intake of booze as per the BCRs (Band Council Resolutions) and bylaws of the community, to giving people rides at night when they need it.”

The PeaceKeepers work with police but themselves don’t carry weapons or stab vests.

“So when we got here and I speak to community members, I talk to all the leadership,” Shuttleworth explained. “All the directors. And then I talk to the average person on the street. The store owner. The people who are walking around who are bothered by all of this and they got together. They help me. I get 70, 80 calls a day.

“We’ll actually go to community, I assess what the problem is, and I hit it directly. Because every community’s unique. In this community here, we have challenges we didn’t face in other communities where me and my guys are out on the Ski-Doo at 4 o’clock in the morning trying to intercept bootleggers coming in.”

Shuttleworth has worked with three communities so far – Berens River First Nation, O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation, and now Barren Lands – to write up bylaws that give them the jurisdiction to maintain the peace, like First Nation band officers would.

“When we got here there was 11 people who were wanted by the police,” Shuttleworth said. “They had outstanding warrants. It’s hard for the police to come in ’cause there’s only eight members in (the) Thompson subdivision for rural, and only four on duty right now. So when they come in, they don’t have the time like that. But also a few of these people are bigger sources of trouble here so we assisted them in getting them into custody.

“We know who they are, we know they’re in community. I speak to them and I just tell them, look the police are coming. They know where you are, you have a warrant for your arrest. If you turn yourself into us, we’ll try and get the police to release you if it’s possible. And if you have to go into custody, it’s a lot better to come and see us rather than them enter your house with a warrant and knock the door down and make a scene for all the persons involved in your life.”

The benefits of getting help from the Anishinaabe PeaceKeepers are far reaching.

“We’ve been told there’s been a drop in people reporting to the nursing station for alcohol and drug-related injuries or events by 90 per cent,” explained Shuttleworth. “School attendance has gone up considerably. We’ve also been told that medivacs have dropped.”

Chief Sewap says “it’s like the crime activity and the violence just completely stopped after Wayne and his crew showed up.”

“The biggest difference we saw was, especially from Awasis (in northern Manitoba), last month they had zero calls from the communities compared to the month before they came there,” the chief added. “They had calls practically every week. Three, five calls, sometimes more.”

The results are felt elsewhere, too. O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation, where there was formerly a high truancy rate, won a national award for perfect student attendance while the Anishinaabe PeaceKeepers were there.

Shuttleworth, who has now been at Barren Lands First Nation for 29 days, has been extended by the community to keep patrolling until May 11. Meanwhile the Anishinaabe PeaceKeepers say they are ready for other communities that need their help.

The response from the community has been extremely positive.

“People want their community safe,” Shuttleworth said. “Everybody’s sick of this. The kids are telling us they can play out at night. They can walk around. There’s not an issue anymore, they’re not scared.

“They’ve never heard kids playing outside in months, and every night you see kids on toboggans. Sliding. There’s kids everywhere now. The kids see us, they laugh, we were at a kid’s festival helping with that the other day. So we just try to do everything we can in community and not be the police, because we sure as hell are not the police.”

Chief Sewap says to maintain the safety, they need help and support from organizations like Keewatin Tribal Council, Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak and the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs. He hopes nations across Canada consider tackling their issues with support from community, and with groups like the Anishinaabe PeaceKeepers.

“Do the same thing that I did. Reach out to the community members first. Have a public meeting.”