One night in 1940, Henry Borden, Gordon Scott and Robert A.C. Henry invited their boss, C.D. Howe, Canada’s wartime Minister of Munitions and Supply, to the Château Laurier, where the three men were living. The trio wanted Howe to consider their solution to a thorny problem: how to discreetly purchase the raw materials Canada needed to help fuel

the Allied campaign in Europe

— silk, rubber and the like — without driving up prices.

Borden was a Toronto corporate lawyer, Scott a chartered accountant from Montreal, while Henry, also from Montreal, had worked in both business and government. The group’s proposed fix involved establishing “dummy“ companies headquartered far outside of Ottawa with no apparent ties to the federal government to quietly make the required purchases.

Howe immediately endorsed the plan.

These were not Canada’s first Crown corporations, but

during the Second World War

, the practice of forming such arm’s-length enterprises went into overdrive, with 28 becoming established by the Department of Munitions and Supply alone by 1945. These far-from-here businesses could execute orders discreetly and with little heed to bureaucratic red tape.

As war broke out in Europe, Howe and

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King

knew Canada was not yet in any position to provide Britain with the support it needed. Howe believed that only a team of skilled businessmen could act fast enough. Now he’d assembled private-sector men like Borden, Scott and Henry.

“It was all done by orders in council — that’s the key to this whole story,“ says historian and author Allan Levine. “It was war, the War Measures Act was on, and Howe gave these guys a lot of leeway. If they wanted something done, they just drew up the order in council, it was sent to Howe, and he made sure that King signed it — and it was away we go.“

Wartime Crown corporations would subsequently supply the U.S. with some of the enriched uranium used in the Hiroshima atomic blast — sourced from the Northwest Territories — and also helped replace the rubber that Japan’s conquests in the Pacific put out of Allied reach with a synthetic variety manufactured in unglamorous Sarnia, Ont.

It all happened because of Howe’s crack team of hand-selected men — and at the Château, amid the hat-check girls, elevator operators and bellboys “with their singsong piping voices.“

As Levine notes in his latest book,

The Dollar A Year Men: How the best business brains in Canada helped win the Second World War

, Ottawa in the 1940s hosted an army of industrialists, lawyers, accountants and other professionals who joined the war effort against Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan and fascist Italy.

These men — almost all of them were men — were nominally paid a dollar a year (although, as Levine points out, the payment scheme was largely a myth). Their efforts put Canada firmly on a war footing and helped catapult the Canadian economy from an agrarian to a modern, more urban enterprise — the world’s fourth-largest industrial power by war’s end.

And though they were far from soldiers, their project was not without risk: in 1940, Howe himself survived the torpedoing of the ship ferrying him and several of his dollar-a-year men to England for consultations with Winston Churchill’s government; Scott, one of his lieutenants — and one of the men Howe met with earlier that year at the Château to discuss the creation of new Crown corporations — perished in the same U-boat attack.

At the height of the war, as many as a hundred of Howe’s recruits lived and worked out of the Château (

“Ottawa’s swank Château Laurier swarms with them,”

Time

noted in 1940). To step into the hotel today and walk its halls is to glimpse where many of their exploits came to pass — the hatched plots, internecine feuds, maybe one or two extramarital adventures, the only frat house in Ottawa stately enough to satisfy Canada’s high-flying captains of industry.

But it functioned as something more than just a clubhouse or shelter. The hotel’s freewheeling atmosphere arguably made it a player in its own right, nurturing the hybridization of business and bureaucracy that helped lead to Canada’s wartime success.

“It may seem strange to credit a hotel for what was accomplished,“ as the legendary journalist Peter C. Newman wrote. “Howe’s shock troops levitated Canada by its own bootstraps. And it all happened in the common rooms of the Château.“

***

The Château has been called Canada’s

”Third Parliament”

and, as Newman also once put it, “an annex to the East Block, which in those far-off days housed the prime minister’s office as well as the entire external affairs department.“

The relations between Mackenzie King and Howe, his minister, on the one hand, and the entrepreneurs and industrialists they enlisted as dollar-a-year men, on the other, were often strained. The industrialists were frequently Conservatives, suspicious of unions, and habituated to dictatorial management styles; their political masters were Liberals, to a large degree sympathetic to labour, and comfortable with compromise.

Sent to Ottawa in 1943 to compare it to the U.S. capital, Denys Smith, Washington correspondent for

The Daily Telegraph

newspaper in London, wrote that the Château’s way of throwing together people with clashing interests enhanced Canada’s wartime capacity.

“Such opportunities for legislators, civil servants, members of the press and the public to mingle, talk or at least see each other under the same roof produce the right psychological atmosphere for the united effort,“ he wrote, “and this may well be a contributory reason for the lack of any such interdepartmental and intradepartmental friction as often bedevils Washington’s scene.“

The Château was crowded because Ottawa was crowded. More than a thousand soldiers were camped at Lansdowne Park. Rockcliffe Airport, used to train air force photographers and administrators, reportedly housed 500 more. According to a 1941 Maclean’s article, the civil service had authorized 30,000 new appointments since September 1939 — 20,000 during 1940 alone. In Ottawa, the number of new openings made for a 65 per cent increase.

Ottawa’s new arrivals led to traffic congestion:

“Between eight and nine o’clock in the morning, and again between five and six o’clock at night, the crowded downtown streets look like New York’s Times Square on New Year’s Eve. Suburban-bound streetcars and buses … are packed to suffocation.“

At the Château, staff often stopped booking rooms and booked beds instead, grouping the men by city of origin — usually Toronto and Montreal — writes Joan E. Rankin in her 1990 book

Meet Me at the Château

.

Other reports from the time describe those not lucky enough to get even a bed at the hotel being led — possibly via the tunnel still then open below Rideau Street — to sleep in empty railway cars at the train station across the way.

Given the Château’s distractions, it’s incredible anything of consequence got done there.

With a barbershop, swimming pool and three restaurants, the hotel was “a hub of wartime activity … host[ing] dinner meetings [and] boisterous socializing with Canadian rye whisky and cigars,“ writes Levine.

It housed the CBC’s Ottawa studio (it left the building in 2005), from which Lorne Greene (called the “voice of doom“) broadcast his wartime newscasts.

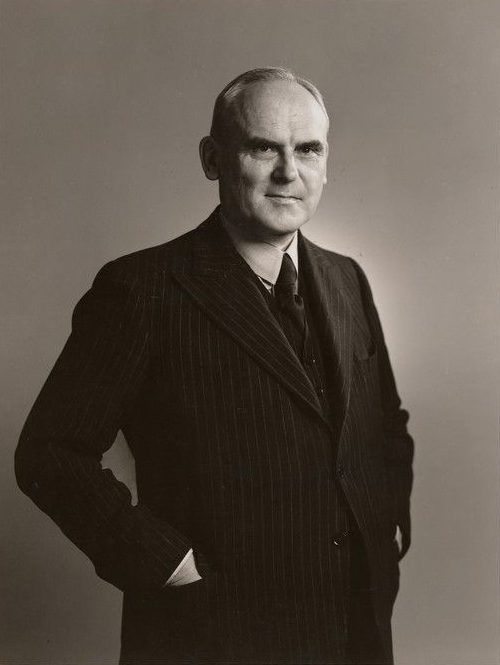

Photographer Yousuf Karsh also lived and kept his studio there.

When Borden, a member of Howe’s team, lived at the Château, it was in his uncle Sir Robert Borden’s sumptuous suite of rooms, set up during the latter’s tenure as prime minister. The younger Borden called the Château a “gossiper‘s paradise,“ Levine reports, and the bar housed below what is now Zoe’s was often called “the snake pit.“

Recalling that women had once been as present in the hotel as were men before the war, one wartime correspondent for Maclean’s lamented that the Château’s habitués had changed:

“Now, nine out of every 10 persons visible in those same tesselated halls are men. Most of them are middle-aged parties of serious mien, carrying fat briefcases and wearing the harried look of having to be somewhere else in five minutes.“

At least some of these serious men had plenty to do.

Driven largely, Levine says, by love of country (and worry for England, still seen as the motherland then in a way that now feels odd), Howe men like Harry Carmichael, Ralph Bell and E.P. Taylor created Canadian aircraft-, ship- and machine-tool manufacturing capacity and chemical and aluminum interests from scratch in just a few years.

They would transform CCM, maker of bicycles and ice skates, into a gun-parts manufacturer, and another company’s soda-fountain division into a factory that churned out bits and pieces of armoured vehicles.

“Workers at a plant that manufactured refrigerators became experts on producing tank turrets,“ writes Levine.

By the end of the war, only the U.S., the U.K. and the then-Soviet Union produced more war products than Canada.

One stat alone tells the story: in 1939, according to Levine, the Royal Canadian Air Force had access to just 270 aircraft. By 1944, Canada’s aircraft industry was pumping out 4,000 planes a year, 16,000 altogether, their names as distinctive as insect species: “Lancaster bombers, Avro Ansons, De Havilland Mosquitos, Boeing’s huge Catalina flying boat, the Curtiss Helldiver and the Harvard and Cornell trainers, among others.“

The total estimated value, in 2025 dollars, for this output: $14 billion.

Of course, not everyone at the time was impressed by Howe’s team. In 1940,

The Evening Citizen

quoted Karl Homuth, a Conservative MP during the war, as saying he thought some of them were “set up in pretty elaborate offices, with rugs and leather chairs, and so on, and he suggested economy could be practised there, in view of the high taxes.“ An editorial in Bowmanville, Ont.’s

The Canadian Statesman

newspaper echoed this distrust: “Drop your tools, your hoe and rake; put on your seersucker suit and starched collar and hie to the Château Laurier for a ‘see‘ at the sights — if you can get past men from all over Canada who crowd the rotunda seeking government jobs or wartime contracts.“

During a 1941 visit to Ottawa by the CBC’s much-loved Happy Gang comedy ensemble, covered by

The Ottawa Journal

newspaper, troupe announcer Hugh Bartlett announced: “I‘m standing in Wellington Street at five tonight so as I can go back to Toronto and tell the boys I was trampled on by herds of beautiful young things who work for the dollar-a-year men.“

But Levine mentions only one instance of (perhaps only emotional) infidelity among the men he profiles in his book.

Leaving his wife and children at home, hard-charging Vancouver lumberman H.R. MacMillan, then in his 50s, moved into the Château and arranged for his 38-year-old secretary, Dorothy Dee, to join him during his work with Howe. Levine quotes MacMillan biographer

Ken Drushka

, who wrote that the relationship “evolved into a more personal and intimate one than that of employer and secretary … a close emotional partnership that lasted as long as they both lived.“

The Château was the stage for so much of what happened in Ottawa during wartime — dramas of political ambition, competition, and the forging of a nation at war.

And occasionally even more human things. Hotels are known for that sort of thing, too.

Our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark our homepage and sign up for our newsletters so we can keep you informed.

Related

- Deachman: These Second World War veterans deserve honour and thanks

- Hear the ‘Last Voices’ of Second World War veterans at new War Museum exhibit