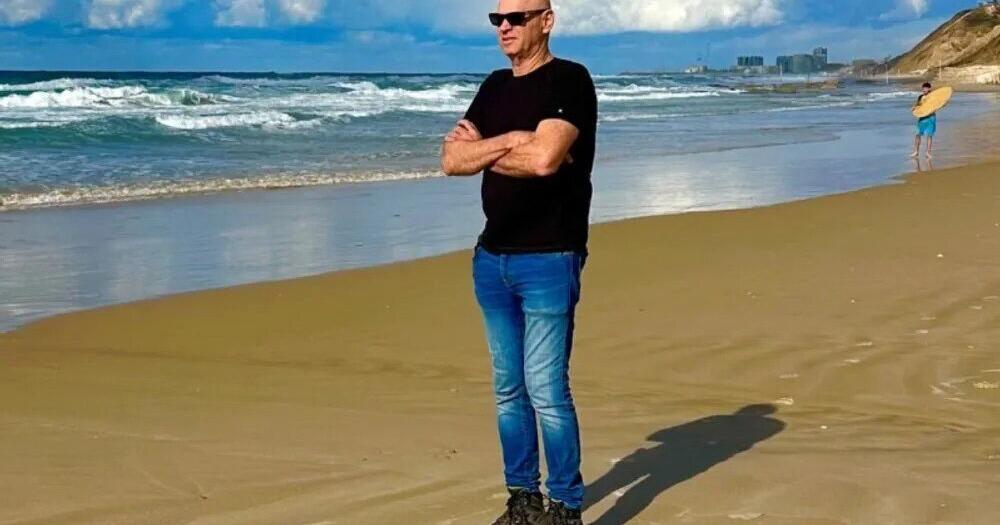

He speaks with a quiet authority, a man whose 35-year military career taught him the value of measured words. But on the morning of Oct. 7, 2023, Gen. Noam Tibon abandoned all caution. With his wife Gali at the wheel, the retired Israeli army general drove his family Jeep into a war zone, risking his life to rescue his son and grandchildren from Hamas attackers. Their journey, and the family’s race against time, is now chronicled in a documentary “The Road Between Us: The Ultimate Rescue,” which premieres at the Toronto International Film Festival on Wednesday.

Last month, the film became a lightning rod for controversy when TIFF pulled the doc from its lineup, citing a lack of “legal clearance of all footage,” which would include videos filmed by Hamas. After public outcry, TIFF reinstated the film. TIFF CEO Cameron Bailey apologized to Tibon and director Barry Avrich.

Tibon and Avrich spoke to the Star as they prepared for their film’s TIFF debut.

Noam, tell us what you were thinking: to hop in your Jeep and drive into the unknown, knowing that you were likely to be killed.

Tibon: Let’s say (I had) a gut feeling in the heart, not the brain. Because the brain said, “OK, there’s a military (to rescue my family),” but the heart said, “You have to go there.” And sometimes you have to follow your heart, your fatherly feeling.

But wouldn’t a military guy tell his troops that you’ve got to use your brain, not your heart?

Tibon: Yes. Once you face the enemy, you have to use your skills, you have to use your experience. But the main decision (I made that day) was not to wait for somebody to do the job and to go.

Avrich: That’s the sole reason (I was) attracted to this film. I’m not a political filmmaker at all, and I couldn’t possibly have a position on this conflict. But you get that text message at 6:30 in the morning that your son or daughter is in trouble. As a father, what would you do? What lengths would you go to? You’re going to call 911, and then what — are you going to watch the news? This is what intrigued me. This film is, to me, a story about a family, not politics or a flag.

Barry, it’s hard to describe the Hamas bodycam footage in the film as being “restrained,” because of the brutality it shows, but you’ve said you didn’t use the worst of the material.

Avrich: I’ve seen all of the footage, every frame, and it wasn’t my intention to horrify people. It was to specifically retrace Noam’s steps in terms of what he saw along the way versus, you know, to colour the film one way or the other. If (Noam) was was standing here at a junction or he saw this as he was walking into the kibbutz, this is what happened in real time and it was filmed — either by closed circuit television security cameras or the Hamas body cams.

How difficult is it to isolate this heroic story and the atrocities of Hamas when Israel has come under so much pointed criticism for such large-scale loss of innocent life in its response to Oct. 7?

Tibon: I think that, in many ways, this movie is about a father and a mother trying to rescue their family. That’s it. Of course I’m in Israel and I’m very involved in Israel, but I put everything aside because the movie is about a family. What I would like that people get from the movie (is to ask,) “What would I do in such a situation?” It can be a terror attack, it can be a disaster, it can be whatever. How do you fight your own fear? And because Barry is from Canada, he’s not part of the story of the Israelis and the Palestinians. He came to take a snapshot of a (smaller) story.

Avrich: You can’t ignore anything that’s going around you. But again, I picked one story, and that’s it. And this was a story about a father saving his family, no matter what region you’re from. I’m looking for the commonality and the universality of this story, period.

What kind of criticisms do you anticipate the film receiving?

Tibon: I hope many people all over the world will watch it and, you know, make their own (opinions about it).

Avrich: People can criticize it all they want after they’ve seen it. My issue is people who are mischaracterizing the film or criticizing it before they’ve seen it because they automatically think it’s an Israeli film and that’s why it should be discounted.

Barry, you’ve shown many of your films at TIFF and you’re also a former TIFF board member. Have you reconciled with TIFF over what happened here, cancelling and then reinstating your premiere?

Avrich: Cameron Bailey and I had a conversation on the opening night of TIFF … That was important to me to express my feelings of how all this went down … At the end of the day, the audience decides what they want to see. If they don’t want to come and see the film, don’t come, pick another film. What is the point in protesting a film? The festival started in ’76 with a documentary about student activists. And the founders were very proud of having a controversial film at TIFF. So the programmers today shouldn’t be ashamed of having controversial films. It’s in their mission statement: debate and dialogue.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.