In early July 1981, Barry Deeprose stopped to read a New York Times article pinned to a bulletin board at the Gays of Ottawa centre, where he volunteered as a peer counsellor.

The

article described

a rare and often rapidly fatal form of cancer diagnosed in 41 homosexual men, mostly in New York City and San Francisco.

“The cancer often causes swollen lymph glands, and then kills by spreading throughout the body,”

the newspaper reported

. “Doctors investigating the outbreak believe that many cases have gone undetected because of the rarity of the condition and the difficulty even dermatologists may have in diagnosing it.”

Investigators did not know whether an unidentified virus or environmental factors were behind the outbreak.

Deeprose, now 82, has a vivid memory of reading that newspaper clipping.

“This was the first announcement of the AIDS epidemic, but we didn’t have a name for it then,” he said.

It would be another year before the mystery disease would come to be described as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, AIDS. The following year, in May 1983,

French researchers reported

the disease was caused by the human immunodeficiency virus, HIV.

Deeprose was then a federal public servant, a human resources expert within the Department of National Defence.

He also volunteered two nights a week as a peer counsellor with Gayline, a phone service offered by Gays of Ottawa, which formed in 1971 following the landmark “We Demand” rally on Parliament Hill, the country’s first large-scale gay rights demonstration.

Deeprose answered phones three hours a night on Gayline. Most of the calls – about two-thirds – were from pre-Internet trolls who spewed invective and threats. The other callers were young men seeking advice about how to come out of the closet, or how to connect with Ottawa’s gay community.

Deeprose found the work rewarding since it affirmed his own experience. But as the spectre of AIDS loomed, he began to worry about the advice he was offering – and the potential peril to which he was exposing callers by directing them to the city’s hook-up spots.

“What bothered me is that people were calling us, and we were telling them where the saunas were, where the bars were, and if they were sophisticated enough, then where the outside cruising areas were,” he said. “And my concern was that we were putting people at risk without any information.”

Deeprose carefully followed news about HIV/AIDS in an attempt to understand how best to protect people against the disease and how to identify its symptoms.

The first Canadian case was diagnosed in 1982. The following year, in August 1983,

Ottawa’s Peter Evans

put a face on the crisis when he became the first person in Canada to speak openly about living with AIDS. Evans had recently returned home to Ottawa from London, England, where he was working as a costume and set designer.

He died at The Ottawa Hospital in January 1984. AIDS cases in Canada were then doubling every six months.

Deeprose was not an activist by nature, but he found the lack of public health information about AIDS maddening. So he became more involved in the gay community, first as a board member at Gays of Ottawa, then as a founding board member of Pink Triangle Services, the country’s first official gay charity. It provided health and social programming to Ottawa’s gay and lesbian community.

The AIDS epidemic had, by then, struck near to Deeprose. A close friend, Tony Ibbitson, was rail thin and suffering the persistent, dry cough that was a hallmark of the disease. (He would die from AIDS in September 1985.)

At the Pink Triangle Services board meeting in July 1985, Deeprose proposed that an AIDS Committee of Ottawa be created to spearhead prevention efforts and assist the dying. The motion, seconded by board member Bob Read, carried. (Read would later die of AIDS.)

“I have to say, quite frankly, I was hoping someone else would do something about AIDS in Ottawa,” Deeprose told an interviewer with the AIDS Activist History Project.

Launching the AIDS committee would put Deeprose at the heart of an extraordinary and harrowing human rights battle.

“We were quite besieged when we founded the AIDS committee,” he said. “We seemed to have to fight for everything.”

***

Barry Deeprose was born and raised in Calgary, where he attended Colonel Walker Junior High School and Western Canada High School. A top student, he was editor-in-chief of the school newspaper and dreamed of a career as a teacher or psychiatrist.

He went to the University of Saskatchewan then did graduate work at the University of Washington, where he came out as gay.

Unable to secure a teaching job, Deeprose waited on tables in Vancouver for two years before moving to Ottawa in 1975 for a job in the public service.

It was, he said, like stepping back into the 1950s: Ottawa was a deeply closeted city compared to Vancouver or Seattle. Some people maintained two names – one for their straight life and one for their gay one – while others lived as “weekend gays” who would travel to Montreal or Toronto to give expression to their sexuality.

There was a “sort of paranoia” in Ottawa, he said, that remained from the federal government’s purge of gay civil servants in the 1950s and 60s.

But what Ottawa lacked in flamboyance, it made up for in bureaucratic vigour. The city’s LGBTQ community had a thriving newspaper, GO Info, along with a political organization, Gays of Ottawa, and a social services organization, Pink Triangle Services.

The AIDS Committee of Ottawa held its first public meeting in October 1985 as the AIDS epidemic sowed fear. The meeting attracted hundreds: People desperate for information spilled out the door to hear Dr. Gilles Melanson, the first openly gay doctor in Ottawa, relate his current knowledge of AIDS.

Researchers had yet to decode the T-cell-destroying disease, and there were fears the disease could be contracted by coming into contact with a sick person’s saliva or blood. Dying AIDS patients were often treated like lepers. In Ottawa hospitals, food would be left outside the door because staff members were afraid to go inside.

Anyone in the gay community with a cold, a rash or diarrhea worried that it foretold the onset of AIDS.

“It was a crucible of fear, anger and grief,” Deeprose said of the time.

***

The AIDS Committee of Ottawa, a volunteer organization with a shoestring budget, faced an enormous task.

Bob Read took responsibility for AIDS prevention and education, while Deeprose accepted the job of delivering support services and palliative care to those with AIDS.

One of the committee’s first initiatives was a condom blitz. Six committee members, including Read and Deeprose, went to bars and bath houses in Centretown handing out AIDS information pamphlets and free condoms. (Their adopted slogan, “Play Safely,” did not sit well with the War Amps, which used the same slogan; the organization issued a cease-and-desist letter to the AIDS committee.)

Deeprose tried to launch a support group for people living with AIDS, but at first, no one would attend the meetings because of the stigma attached to the disease. So, he formed a new volunteer group that he called “the buddies” to reach out to them.

The buddies were trained to care for people with AIDS, and help with shopping, cleaning and other household chores. A palliative care chaplain, Sally Eaton, and a reverend with the Metropolitan Community Church, Ron Bergeron, helped with end-of-life care. (Bergeron would die of AIDS in 1990.)

With no treatments available, AIDS was then a death sentence. The disease’s victims often succumbed to opportunistic infections that overwhelmed their damaged immune systems. Some people, Deeprose said, literally coughed up their lungs.

“The scenes were out of a horror movie,” he said.

The AIDS Committee of Ottawa received some provincial funding in 1987, which allowed the organization to hire an executive director, David Hoe. Hoe had come of age in Britain during the 1960s gay liberation movement, and established Britain’s first gay and lesbian help line.

That liberation movement, Hoe said, primed the gay community for the political battle that ensued with AIDS.

“If AIDS had hit in the 1940s or 1950s, it would have been completely different,” he said in an interview. “But by the 1980s, we were pretty well honed in many ways in terms of standing up to the systems of prejudice: of law and of policy.”

The AIDS Committee of Ottawa had to overcome conservatism, homophobia and misinformation.

Ottawa councillor Jacquie Holzman, for instance, opposed regional funding for an AIDS education and prevention campaign, arguing that enough information existed for people to manage their own health without the need for taxpayer dollars. “People who have AIDS are going to die anyway,” she told reporters.

Also read: Forgotten no more: The story of the first man to die of AIDS in Canada

In late 1985, the first commercial blood test for HIV, the retrovirus that causes AIDS, became available in Canada. It triggered an emotional debate that would play out for years in the gay community about whether or not to be tested.

Some believed it was better not to know since there was then no effective treatment for AIDS. What’s more, since AIDS was considered a sexually transmitted disease, test results were reported to the region’s medical officer of health, who then traced an infected individual’s previous sexual contacts.

To make matters worse, some men who had sex without disclosing their HIV-positive status were being charged as criminals.

There was a feeling among some in the community that it was simply better not to know one’s HIV status since only bad things flowed from it.

As the first chair of the Ontario AIDS Network, Deeprose lobbied the government for anonymous testing to circumvent those concerns.

Some local politicians pushed for a more draconian approach. In July 1989, Ottawa Regional Chairman Andy Haydon wrote that the best way to deal with the exploding epidemic was through mandatory testing. (Haydon also suggested the disease could be transmitted by kissing.)

He told reporters there should be mandatory AIDS testing for regional employees, high school students, immigrants, prisoners and hospital patients.

The AIDS Committee of Ottawa protested outside his offices.

Dr. Steve Corber and Dr. Ian Gemmill, the region’s top public health officials, both opposed anonymous testing on the grounds that it would impair their ability to control the spread of the disease. They called it a dangerous public health precedent.

Gemmill, the associate medical officer of health, issued more writs under Section 22 of Ontario’s Health Protection and Promotion Act than any other public health official in the province. The writs were issued to people who were infected with HIV and continued to engage in sexual activity; it ordered them to stop having penetrative sex, and report all of their sexual contacts, or face a $5,000 fine.

In 1991, Gemmill issued 17 of the 20 such writs used in Ontario.

“It’s not that we have all the cases,” Gemmill told the Toronto Star. “It’s just that other health officials hesitate because they have been told the orders are too draconian.”

Deeprose and Hoe lobbied provincial and federal health officials to introduce anonymous testing, and to reject Gemmill’s approach to prevention.

“We said that keeping the names out of it was a better prevention strategy for both those living with and those at risk,” Hoe said. “The argument was that if people had an environment in which it was easier to disclose or discuss HIV, then both prevention and support would be more readily accessible. We needed to create a safe environment.”

The province finally agreed to anonymous AIDS testing in 1992. Deeprose considers it the most important victory of the AIDS-related human rights campaign since it gave people the power to control their own health without fear of government involvement.

“AIDS in gay men really changed the way public health worked,” he said.

Hoe agreed. “It was the notion that people dealing with a public health issue have a right to voice and a right to influence policy,” he said.

Instead of being tested at Ottawa’s sexual health clinics, gay men could now go for anonymous testing at one of the city’s community health centres.

People flooded in for testing, but there was a downside.

“It was utterly traumatic to realize how many people were infected,” said Deeprose. “We realized what a huge job was ahead of us.”

***

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved AZT, the first drug to treat AIDS, in 1987, but it had terrible side effects and its effectiveness diminished over time.

It wasn’t until 1995 that the first protease inhibitor, Invirase, came on the market. The drug would form part of a new approach to AIDS treatment: Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), also known as combination drug therapy, became the standard treatment for an HIV infection in 1996.

HAART began saving lives almost immediately. A 1998 U.S. study found that HAART cut the AIDS death rate by 70 per cent.

The same was true in Canada, where AIDS deaths peaked in 1995 at 1,764. Two years later, the number of Canadians dying from AIDS fell sharply, to 626, thanks to the new drug regimen.

By that time, Deeprose had left the AIDS Committee of Ottawa and returned to Pink Triangle Services, where he again worked as a counsellor on Gayline. He later served as president of the organization.

Deeprose had resigned from the AIDS committee in 1992: He felt the committee was being overtaken by activists more interested in addressing the health needs of injection drug users than gay men.

The committee’s drop-in centre for people with AIDS, known as The Living Room, was increasingly a place for drug users. “People with AIDS who were gay did not feel comfortable there,” said Deeprose, who continued to work on behalf of gay men in other roles.

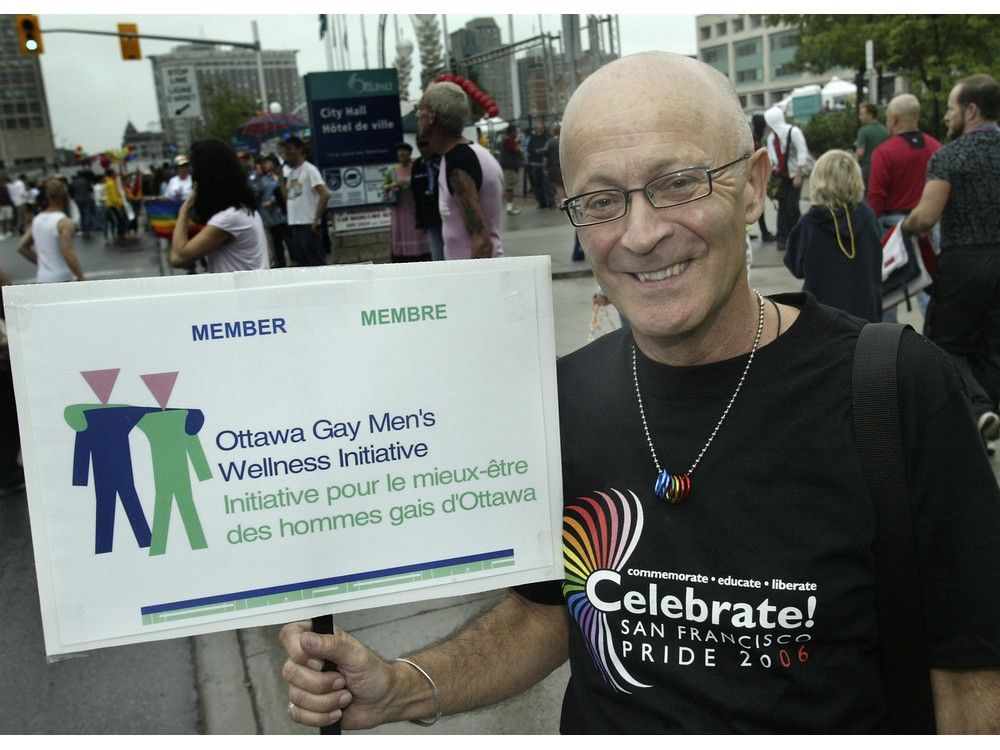

From 1991 to 2001, he sat on the Ontario Advisory Committee on HIV/AIDS, which made recommendations to Ontario’s health minister on AIDS policy. He also sat on a Health Canada reference group to improve HIV prevention for gay men, and chaired the Ottawa Gay Men’s Wellness Initiative from 2002 until 2014.

Hoe described Deeprose – he’s now ailing – as a forthright and bold leader unafraid to take strong public positions during the most difficult of times.

“He was absolutely invincible in terms of fighting for human rights and health and education,” said Hoe, who was in Ottawa recently to visit his lifelong friend. “He was incredibly articulate and forceful.”

In the three decades after the first AIDS case was diagnosed in Canada, more than 18,000 people died from the disease in this country.

• Barry Deeprose was unable to be interviewed for this story because of his health issues. This story draws on a lengthy interview with Deeprose conducted by the AIDS Activist History Project, and by his previous interviews with the Citizen

A brief timeline of HIV/AIDS in the United States and Canada:

July 3, 1981:

The New York Times publishes its first story on a mysterious illness, “a rare and often rapidly fatal form of cancer” that was killing homosexual men in New York and California

1982:

The first cases are reported in Canada

Aug. 20, 1982:

More than 80 people attend a Gays of Ottawa public forum on “gay cancer”

August 1983:

Ottawa-born Peter Evans, a costume designer, puts a face to the emerging crisis: He becomes the first person in Canada to speak openly about living with AIDS

Oct. 1, 1983:

Evans takes part in Ottawa’s first AIDS walk-a-thon from Ottawa to Kingston. It raises more than $5,000

Jan. 4, 1984:

Evans dies

March 1985:

The first blood test for HIV is approved for use in the U.S.; it becomes available in Canada later in the year

July 1985:

Hollywood star Rock Hudson announces that he’s suffering from AIDS; he dies three months later at the age of 59

October 1985:

The AIDS Committee of Ottawa, co-founded by Barry Deeprose and Bob Read, holds its first public meeting

March 1987:

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (F.D.A.) approves AZT, the first drug designed to treat AIDS

1987:

Investigative reporter and author Randy Shilts publishes And the Band Played On, a landmark book on the AIDS epidemic

September 1988:

Bruce House opens in Ottawa to offer emergency housing and hospice care for those with AIDS

November 1991:

NBA star Magic Johnson announces that he’s HIV-positive

1994:

AIDS becomes the leading cause of death in the U.S. for people between the ages of 25 and 44

1995:

The F.D.A. approves the first protease inhibitor, which will form a key part of a new approach to AIDS treatment, combination drug therapy, sometimes known as the AIDS cocktail

1995:

The number of annual AIDS deaths peaks in Canada as the disease claims 1,764 lives

July 1996:

At an AIDS conference in Vancouver, researchers present evidence showing that the combination drug therapy is highly effective

1997:

The number of Canadians dying from AIDS plummets for the second consecutive year, as 626 people die of the disease

Our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark our homepage and sign up for our newsletters so we can keep you informed.