In downtown Montreal, the federal riding of Laurier—Saint-Marie is a hive of cultural activity. Nestled within its boundaries is the historic Old Port, with cobbled streets, quaint galleries and artist studios. Down the road is the Place des Arts, one of the country’s largest cultural complexes, housing seven major venues. Throughout the riding, it’s impossible to escape from within eyeshot of one cultural space or another.

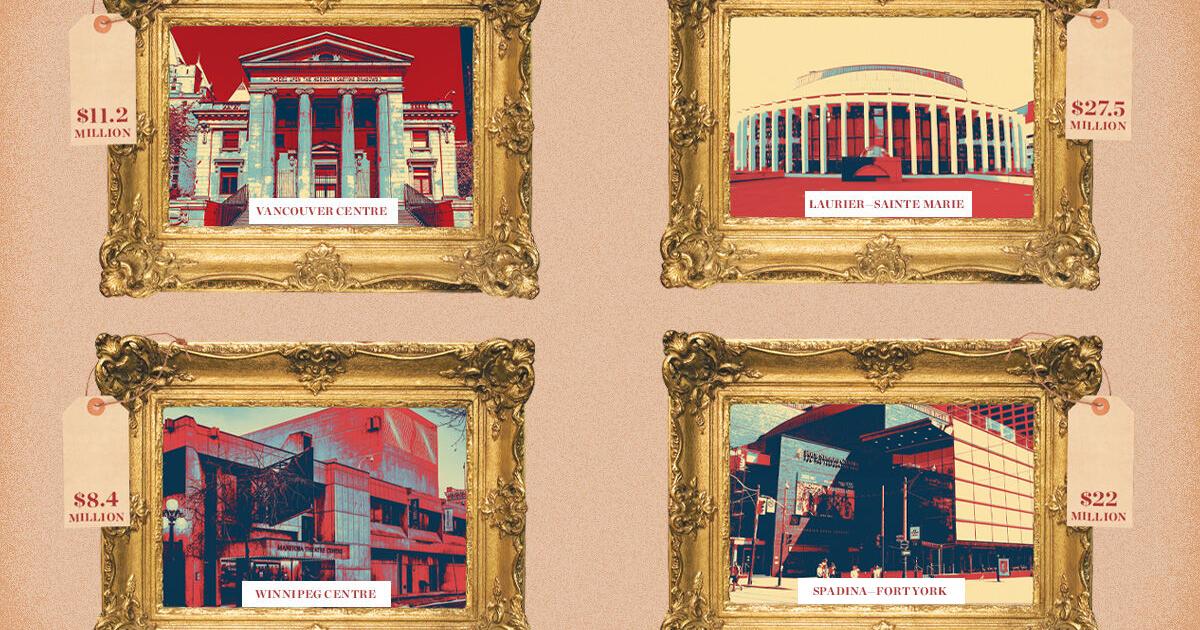

In the 2023-24 fiscal year, artists and cultural organizations in Laurier—Saint-Marie were allocated more than $27 million from the Canada Council for the Arts, the country’s national arts granting body. That’s equivalent to $235 for every resident who lives in the riding, by far the most in Canada, a Toronto Star analysis has found. But in other regions of the country, grants from the national funder amounted to less than a dollar per person. In six ridings, that figure was zero.

To understand how grants are distributed across the country, the Star trawled through public data from the Canada Council, and spoke with artists, arts administrators and cultural policy experts across the country who are familiar with the crown corporation’s funding processes. The analysis found that grants are disproportionately allocated to artists and organizations in large urban centres, while ridings in smaller municipalities receive far less funding on a per-capita basis.

To put the disparities into perspective: the 10 federal ridings that received the most money in 2023-24 are all located in Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver or Winnipeg. They account for three per cent of the Canadian population, yet received 41 per cent of the Canada Council’s total program allocations of $325.6 million. The Star’s analysis found similar trends playing out in funding cohorts going back to at least 2021.

“It’s very peculiar how some of the funding is all spread out, but these disparities have existed for years,” said Martin de Groot, the former executive director of the Waterloo Regional Arts Council. “The problem is also that some of the larger institutions that receive much of the money are so distant from the public and actual practitioners in many parts of the country.”

Funding helps shape Canadian culture

The Canada Council, whose budget is set by Parliament, is one of several public arts funders across the country, along with dozens of other provincial and municipal granting bodies. But as the sole organization with a national mandate, it plays an outsized role in shaping Canadian culture, as well as the economies of local communities.

Funding from the Canada Council has helped to launch shows such as the hit Broadway musical “Come From Away” and supported organizations such as the Stratford Festival, Canadian Opera Company and National Ballet of Canada. According to the grant body, groups that receive operating funding from the Canada Council spend, on average, six dollars in their communities for every dollar of funding that they receive. In 2019, that amounted to roughly $1.5 billion in economic impact.

Artists and industry experts say the findings point to regional inequities in public arts funding, arguing the Canada Council must do more to close those gaps, and to ensure that emerging artists and cultural organizations around the country are as supported as their larger, more established counterparts in major cities.

There are several caveats to measuring public arts funding on a riding-by-riding basis. In some cases, the impact of Canada Council funding extends beyond the home riding where an organization is based. Certain companies, for example, may be headquartered in one riding but conduct their operations or programming in another.

There will also always be funding disparities between urban centres and smaller municipalities, given that more artists tend to work in big cities and large organizations usually operate out of those regions, leading to higher demand for grants in downtown ridings, like Laurier—Saint-Marie.

Lise Ann Johnson, director general of arts granting programs at the Canada Council, acknowledged that funding is “very demand-based.”

“Our decision-making is driven by demand from the sector, external experts and the peer assessors we bring to the table, who assess the comparative merit of the applications,” Johnson said in an interview with the Star. She added that despite apparent regional differences in funding, it’s important to look at application success rates, which are relatively consistent across the country and demonstrate more equity in grant distribution than the raw numbers might suggest.

Should the Canada Council be more proactive?

However, the extent of the disparities between federal ridings raises questions about whether the Canada Council should be more proactive in engaging with communities underserved by the arts, instead of merely responding to industry demand, and whether the funder’s existing practices have created a feedback loop entrenching these regional inequalities.

In de Groot’s home community of the Kitchener-Waterloo region, frustration with the Canada Council’s funding disparities has been simmering for years. But it came to a head in the fall of 2023, when the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony filed for bankruptcy and abruptly cancelled its season.

“It was a tragedy. Those were 50 or 55 musicians who were part of a paid artistic workforce” he recalled. “And if you can’t sustain a symphony, you likely also can’t sustain a newspaper or a gallery. These things are all related.”

Several months later, the now-former MP for Kitchener Centre, Mike Morrice, penned an open letter urging the federal government to reform the Canada Council’s funding processes. The letter, signed by de Groot and more than a dozen other arts leaders in the region, suggested the Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo area received five times less funding, per capita, than cities like Montreal, Vancouver and Winnipeg. It called on the government to boost funding to the grants body and have it adopt the Regional Development Agency (RDA) model, which offers more regional support to the rollout of federal programs and policies.

A spokesperson for the department of Canadian Heritage declined to comment and directed the Star to the Canada Council.

Johnson said applying the RDA model to the Canada Council is “not a particularly well-thought-out” idea. “RDAs are about economic development,” she explained. “It’s looking at the delivery of funding on the basis of economic measures that are really not art specific.”

The Canada Council’s current decision-making process for its various funding programs is largely informed by peer assessment. Professional artists who sit on these peer assessment committees determine whether each application is successful or unsuccessful, before scoring them against a set of criteria. Canada Council staff, using the ranking provided by the peer assessors, subsequently determine how much funding each applicant is awarded. All decisions must then be approved by the program directors, the director general of arts granting programs or the board, depending on the size of the grant.

A possible solution in England

Other jurisdictions have also grappled with regional inequities in public arts funding. According to a report released last month by the Institute for Public Policy Research, a London-based think tank, England’s capital received more than double the public arts funding, on a per-capita basis, compared to northern England between 2023 and 2025. The report called the north’s funding deficit, to the tune of £450 million, a “culture chasm.”

Arts Council England, the country’s national funding body, has attempted to address that disparity by implementing a new program that incentivizes arts organizations in London to move their headquarters out of the city. Eligible groups can receive dedicated funding from an £8-million pool of grants, topped up annually. The initiative comes after Arts Council England was mandated by the government to slash funding to London organizations by 15 per cent and redistribute the money outside of London.

Johnson said she believes the jury is still out on Arts Council England’s more proactive funding approach. Even if it’s successful, she doubts the transfer program could be replicated in Canada given the “geographical differences” between Canada and England.

An issue of arts accessibility

For some arts professionals, the regional disparities in funding also come down to the issue of accessibility. Pam Patel, artistic director of the Waterloo theatre company MT Space and a former peer assessor for various public arts granting bodies, said that many major organizations in large cities that receive funding are largely disconnected from — and inaccessible to — those who live outside those urban centres.

“I’ve sat on juries that’ve denied grants to artists because they aren’t convinced that the applicant is going to have enough people see their show,” said Patel. “Yet we’re giving money to folks and groups who have the means to go above and beyond to reach various diverse communities, but don’t. That’s a very flawed system.”

Publicly funded organizations must do more outreach to audiences and emerging artists outside their home communities, Patel said. And arts funders like the Canada Council, she added, can adapt their assessment criteria to incentivize that kind of outreach.

Patel also said proactively diverting funding into smaller communities can help increase arts accessibility in those areas. “There are so many small- to mid-sized organization and ad hoc groups in these communities that make their funding go far, when they receive it,” she said. “They bring artists into the region, they pay artists that actually live there and their programming is accessible. All this can really change the vibe of a community.”

According to a 2021 study conducted for the department of Canadian Heritage, which surveyed 10,000 Canadians aged 16 and over, only four in 10 respondents said they felt the number of arts and culture offerings in their community was either “good” or “very good.” About half of those surveyed were positive about the quality of the offerings. (The survey employed a non-probability sample, so no margin of error was calculated.)

While the Canada Council does acknowledge regional disparities in how funds are awarded, the national grantor primarily looks at the issue using a province- or territory-wide lens. In its 2023-24 annual report, for instance, the Canada Council acknowledged that Alberta has “historically received a lower share of Council funding compared to its share of artists and population in Canada,” and said it was working with its provincial and municipal counterparts to close those gaps.

But the Star’s analysis found that provincial- and territorial-wide funding analyses do not paint a full picture of the disparities within those regions. The downtown riding of Calgary Centre, for example, was more comparable to the Montreal riding of Papineau in terms of total grants allocated (both received approximately $6.5 million in 2023-24) than a more rural riding in Alberta such as Bow River (which received just shy of $21,000 that same fiscal year).

How to close the gaps

Cultural policy experts who spoke with the Star said that in order for the Canada Council to address these disparities, it needs to re-examine its existing funding model, by which grants are largely broken down into two groups: core and project funding. The former denotes multi-year funding to organizations that can be used to cover operating costs, while the latter refers to a one-time grant meant for a single project.

Project funding tends to be allocated to smaller, less established groups and individual artists, while core funding is usually reserved for larger organizations that have established track records of prior public funding. In the 2023-24 fiscal year, some 47 per cent of the Canada Council’s total funding was allocated for core grants while 53 per cent was for project grants, according to the public funder’s annual report.

Kelly Wilhelm, head of the cultural policy hub at OCAD University, said the current model doesn’t match the demand of the sector, one with a burgeoning cohort of smaller, independent artists and groups. “The organizations with history, who have been receiving this money for the longest time, tend to get more money than the newer organizations,” she said. “This does exclude the same level of granting to newer organizations, newer art forms and some regions of the country.”

Michael Jones, the former CEO of SK Arts, Saskatchewan’s public arts funder, said the concept of core funding presents a conundrum. “It can support more artists and make more opportunities available than project granting. It can also provide more stability for the sector, because typically, once you’re in a (core) program … it’s pretty hard to get pushed out of it.”

But Jones said he feels the allocation of core funding should be more flexible: “Organizations that receive operating funding shouldn’t take it quite so much for granted. And setting a goal and saying 50 per cent of grants must be project funding, which is what the Canada Council is doing, seems like a false target.”

Wilhelm says the issue of the Canada Council’s funding model is important, yet isn’t discussed openly enough. “We don’t tend to debate it too publicly because it would have massive implications for organizations across the country that have been built based on the way the system has worked in the past,” she said. “But unless there’s a conversation around it … that pattern we’re seeing is going to be pretty ingrained.”