The CurrentTeaching teens to get smart about their money

Shannon Lee Simmons has seen first-hand how teenagers’ lack of financial understanding can cause conflict in families.

As a certified financial planner for the last 15 years, she mainly deals with adults. But after she started doing budgeting sessions with some of her clients’ younger family members, she quickly realized that teenagers face unique financial challenges.

Due to the prevalence of digital technologies, a lot of teens may have never held cash in their hands. Without that physical relationship to money, Simmons argues it can become an abstract idea which is harder to grasp its real-world value.

“You can part ways with it in a way that feels less scary. When you have it, it doesn’t feel like you’ve earned it. When you get rid of it, it doesn’t feel like you’ve spent it,” Simmons told The Current’s Matt Galloway.

Simmons also discovered that existential problems like the climate crisis and declining youth employment rates in Canada has made some teens adopt a wants-based, “you only live once” attitude.

Youth unemployment high while some employers trying to hire

The youth unemployment rate in Canada has hit 14.6 per cent, the highest it’s been since September 2010, barring the pandemic years. But what’s the solution? Liam Britten spoke to bosses, job seekers and experts for their thoughts. NOTE: A banner in this story erroneously states that youth employment is high. It is meant to read that youth unemployment is high. A former title with the same error has been corrected.

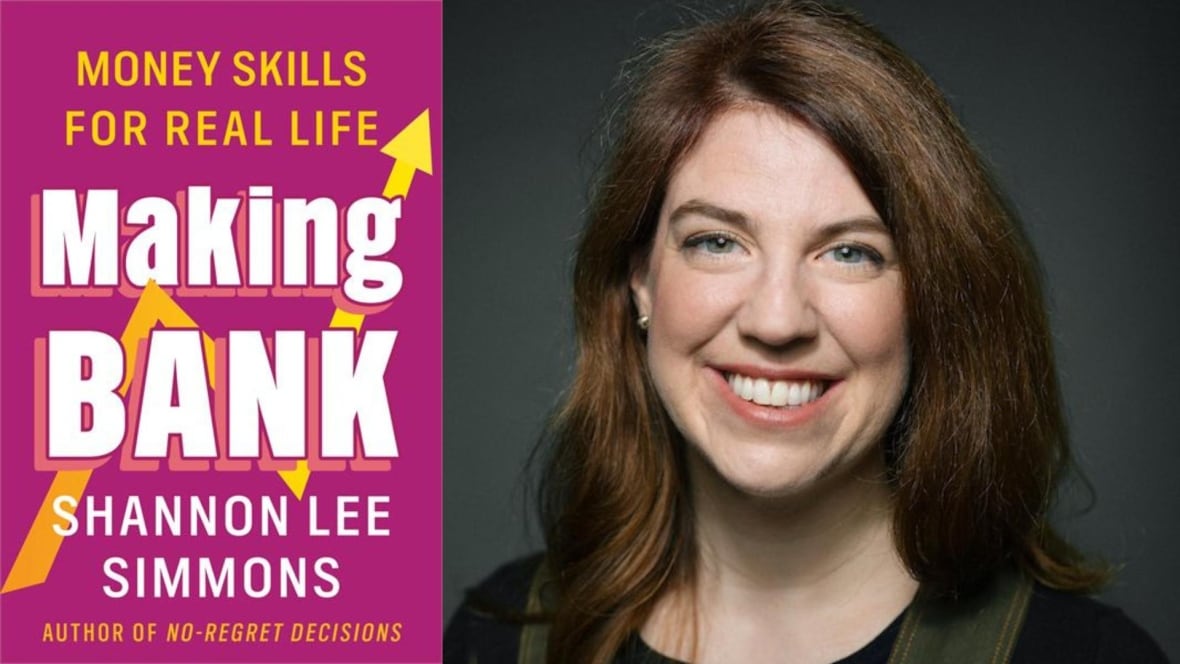

In her book, Making Bank: Money Skills for Real Life, she aims to help teens track, save, spend, enjoy, and grow their money. Here’s part of her conversation with Galloway about helping teens develop their financial literacy.

What do you tell them [young people] about how to become aware of budgeting?

I tell them to get back to basics. If they get an allowance from their parents, get that out of their spending account. Once you have access to it, it feels like fair game, so getting it out of there is important. Pretend like it’s not even yours so that you know your limit and spend within it.

When something doesn’t work out, troubleshoot it instead of feeling like a failure. I had a lot of parents say, “I can feel myself handing down my financial trauma and my financial relationship to my kids.” Imagine a bunch of kids who’re really confident talking about money, know how to pivot it, know how to use it like a tool.

What is unhappy spending?

It’s the idea of mindfully choosing where you’re spending money so you get the most joy. I talk about it as an emotional return on investment. Look at where your money actually goes and then rate it out of five. Five out of five is like, “I love that, I’d never want to get rid of it.” One out of five is like, “I had to spend that and I really regret it” or “I don’t remember it.”

For some kids, going to Starbucks with their friends is a five. It’s the social thing that they do to get independence together; it’s so important.

When they hear their parents saying things like, “Don’t waste your money. That’s so silly. Why are you doing that?” that’s introducing the idea of shameful spending.

Hopefully, this is giving them the language to say, “No, I don’t actually need that cookie at the cafeteria. I don’t need to spend money at the mall because I’m killing time. I’m going to save the money I do have to spend on the things that give me joy.”

This is great because that’s a mindful choice and it’s teaching that decision-making process in a way that gives permission to enjoy spending money so you don’t resent the savings. That’s the whole point.

A lot of kids we spoke with have real worries about money, about what it means to them and how it’ll define their lives. How do you talk to kids about the fear that they could end up behind?

They know a lot; this demographic is plugged in. They know about the economy and so one of the things that I consistently talked to them about was the fear around going to post-secondary [institutions] and whether or not it’s worth the loans. I heard constantly, “Well, if I go into debt, it might be five years until I get a job and I’ll have to live at home.” These are the stakes for many of them.

I’m explaining that your biggest asset is your future income and showing them you want to look at school as an investment in your future income. Thinking about it like that was really eye-opening. Even if I earn a modest income, that’s millions of dollars over my lifetime. That’s exciting; that makes me less afraid to go to school.

I think there’s an undercurrent of, “Why should I try? I’m just going to do what I want [and] long-term doesn’t really matter” with a lot of youth. What I’d suggest is acknowledging them and saying, “I know how scary it is.”

Practice the habits that you need so it’s less scary down the road. Once you develop that habit and it becomes second nature, confidence moves up and anxiety goes down.

That’s a natural impact of having savings. You look at it and you feel comfortable. The dollar amount doesn’t really matter, it’s about the fact that you feel more in control. If we can get kids practicing the habit, I think their anxiety might go down, too.