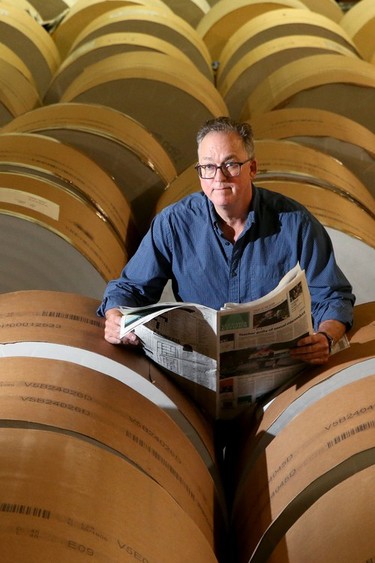

The Ottawa Citizen’s Andrew Duffy and Eganville Leader’s Gerald Tracey reflect on long careers in a wonderful, troubled business.

“Gerald’s out on a job.”

I’m supposed to meet the editor and publisher of the Eganville Leader for a Friday morning interview, but as the paper’s receptionist explains, the news has once again hijacked Gerald Tracey’s life. An overnight fire in a nearby campground has heavily damaged two trailer homes.

The 72-year-old Tracey is at the scene to take pictures and get the story.

THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Unlimited digital access to the Ottawa Citizen.

- Analysis on all things Ottawa by Bruce Deachman, Elizabeth Payne, David Pugliese, and others, award-winning newsletters and virtual events.

- Opportunity to engage with our commenting community.

- Ottawa Citizen ePaper.

- Ottawa Citizen App.

SUBSCRIBE TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Exclusive articles from Elizabeth Payne, David Pugliese, Andrew Duffy, Bruce Deachman and others. Plus, food reviews and event listings in the weekly newsletter, Ottawa, Out of Office.

- Unlimited online access to Ottawa Citizen and 15 news sites with one account.

- Ottawa Citizen ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles, including the New York Times Crossword.

- Support local journalism.

REGISTER / SIGN IN TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

THIS ARTICLE IS FREE TO READ REGISTER TO UNLOCK.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments

- Enjoy additional articles per month

- Get email updates from your favourite authors

Sign In or Create an Account

or

Tracey knows from his five decades of experience that a front-page photo of a car crash or fire sells more papers than a grip-and-grin of a prize winner or politician. It’s why the paper, in this quiet town 90 minutes west of Ottawa, is known by locals as the Eganville Bleeder.

The Evening Citizen

The Ottawa Citizen’s best journalism, delivered directly to your inbox by 7 p.m. on weekdays.

By signing up you consent to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc.

Thanks for signing up!

A welcome email is on its way. If you don’t see it, please check your junk folder.

The next issue of The Evening Citizen will soon be in your inbox.

We encountered an issue signing you up. Please try again

Tracey is unreservedly proud of his paper’s winning formula.

“We’re a newspaper that reports on everything and anything that is of news-worthiness in the community – as long as we know about it,” Tracey explains after his return to the office. “Our commitment is to give the people a newspaper they can enjoy.”

A self-described workaholic, Tracey helps to assign, write, edit, photograph and lay out each week’s newspaper. He sells advertisements, keeps a police scanner at home to track the region’s emergency vehicles, and drives to the dump every Saturday with the office garbage (“If you want to socialize in the country, you go to the dump,” he says. “You’ll pick up all kinds of stories”).

Last night’s fire turns out to be a story about tragedy averted in the crowded Smith’s Bay Campsite.

“They’re lucky,” Tracey says. “It started in one corner, but if it had been in the middle of the park, it might have been a different story.”

Compact, amiable, bearded and energetic, Tracey shows no obvious signs of the heart trouble that nearly felled him. A heart attack 10 years ago led to a triple bypass and stent surgery. Earlier this year, he had a pacemaker installed.

Part of his reporting staff is also hobbled. Seventy-year-old Terry Fleurie is using a walker following his second knee operation.

Last week, Fleurie told Tracey he was worried about how they’d fill the paper with local town councils on hiatus in July. “Don’t know what we’re going to do for stories, boss,” Fleurie said.

Tracey told him not to worry. “There’s always something around the corner,” he said.

Sure enough, there has been a steady drumbeat of news this week: The disturbing sexual assault of an 8-year-old girl in Quadeville; a fatal crash on Highway 41, south of Eganville; human remains found in Pembroke’s Riverside Park; the fire at the Lake Doré campground.

“And it’s only Friday!” says Tracey.

The news never stops. But barring a miracle, the 123-year-old Eganville Leader will stop publishing on Feb. 28, 2026.

Tracey has announced the Leader will close its doors on that date because of his advancing age, uncertain health – and inability to find a new publisher. It is a watershed moment in the history of the capital region’s newspapers.

A dip in advertising revenue has made the Leader harder to sell, and Tracey is unwilling to watch someone else drive the paper into the ground.

“I’d rather plan our own funeral,” he says.

Still, he’s worried about suffering another heart attack before the appointed day. Says Tracey: “I don’t want to stick my wife with the decision to close the place.”

***

The fate of the Eganville Leader has been much on my mind lately as I consider my own newspaper arc, which reaches its endpoint with this story.

I began in daily journalism at The Hamilton Spectator in 1985 when I was still in university, but my association with the newspaper business began years earlier. I delivered the Spec as a young boy, first as a poorly paid subcontractor to my older brothers, and then as my own boss.

My route started at a variety store on Erindale Avenue in Hamilton’s east end and encompassed the tidy bungalows of Stewartdale and Rosedale Avenues. The newspaper was a shared experience: Almost every home received an evening paper. On my three streets, I delivered 54 papers while skipping just four or five doors.

My father fashioned a box on wheels connected to my bicycle to hold the day’s deliveries. It meant I should have been able to pick up my papers after school at the neighbourhood depot and have them delivered in time to be home for supper.

I was always late. The problem was I liked to read the paper as I made my way from door to door. Each customer had a designated spot for the paper: some wanted it folded in the mailbox, some inside the front door, others on the back porch, or in the side milkbox. (Milkboxes were small, square doors once used to receive milk deliveries and return empties.)

I would walk the route with my head bent to the paper. I read the front page, the sports front, the city front. It meant I didn’t pay full attention to what I was supposed to be doing, and often ended up with a few newspapers at the bottom of my box.

Who did I forget?

The answer would inevitably come later that evening when an upset customer phoned our house to demand a missing Spectator. I would dutifully get back on my bike to deliver it – or try to figure out where at their house I might have left it: “Have you looked in your milkbox?” Sometimes, I’d have to swipe the well-thumbed paper from our own living room as a replacement.

I left my newspaper route behind when I entered high school, but by then it had afforded me an invaluable gift: the certainty that I wanted a career writing the stories I used to (mostly) deliver.

***

For Gerald Tracey, newspapering has always been a family affair.

His father, Ambrose, bought the Eganville Leader in 1944 from founder Patrick McHugh, who launched the paper in 1902 to compete with the Eganville Star-Enterprise. McHugh promised a paper “bold enough to be honest and honest enough to be bold.”

Ambrose left high school to work at the Leader, where he learned the art of composing metal blocks of type – letters, numbers and punctuation – into broadsheet pages that could be printed. He bought the Leader with his brother, Sylvester, after working as a printer in Rouyn-Noranda, Arnprior and Kingston.

Gerald Tracey learned the printing business from his father. By the time he was in Grade 5, he could operate the linotype machine that set the paper’s type. By Grade 8, he was running the giant flatbed presses that churned out newspapers.

“It instilled in me the spirit of this business,” Gerald says of his childhood.

In October 1968, Ambrose died following a tragic car accident: He blacked out behind the wheel during an asthma attack and, with his foot on the accelerator, smashed into the stone foundation of Eganville Town Hall. He was 55.

Gerald was still in high school. His mother, Lucy, kept the paper going until Gerald’s older brother, Ron, could take over the reins.

Gerald thought about becoming a lawyer, but the ink in his blood wouldn’t abide it. He remembers sitting in his Grade 13 English class at Opeongo High School as teacher Preston O’Grady outlined his expectations for the year. It was September 1971. Gerald’s mind kept drifting back to the Leader newsroom, where he had spent the summer.

At 9:30 a.m., he made the decision that would set the course of his life. He stood up from his desk, excused himself from class, returned his books to the office, and marched over to the Leader. His brother Ron tried to convince him to go back to school, but Gerald’s mind was made up.

“I knew I belonged here,” he says.

Gerald and Ron would work together at the Leader for the next 36 years. Ron retired in 2007; Gerald kept going.

***

When I walked into the Toronto Star newsroom as a summer student in May 1986, newspapers were stupendously rich.

The Saturday Star landed with a thud on doorsteps, so thick it was impossible to fold. It was often more than 250 newsprint pages. A typical classified section boasted 23 pages and listed for sale everything from houses to cars to pianos. If you were looking for a job, an apartment, a used car, a cottage, a companion – even a horse – you would turn to the classifieds. There were seven pages of movie ads, seven pages of career ads, and seven pages of comics.

The paper cost $1, boasted 10 editorial sections, a TV guide (Starweek), and had a paid circulation that topped 800,000.

The Star’s 1986 annual report recorded it as “the most successful year since the paper was founded in 1892.”

The newsroom into which I walked reflected the Star’s wealth and power: It spread like the nave of a vast cathedral over the fifth floor of One Yonge Street. An editorial staff of 400 filled the place with energy, ambition, gossip, stress, humour, vitriol and kindness.

I loved everything about it.

As a summer student, I was at the bottom, which offered a fine vantage point from which to watch and learn. I learned the delicate art of the “pick-up” – obtaining photos from the family of murder/ crash/ drowning victims – how to file on deadline (simple sentences), and why everyone needs a good editor.

I remember covering a story about a Guyanese boy named Gary Rangasamy, who suffered from neurofibromatosis (Elephant Man’s Disease), and had his right arm amputated by surgeons in Toronto. Days after the operation, he held a bedside news conference and – unbelievably – I wrote that he had met reporters with a “disarming” smile.

A fulminating British editor called me that evening, demanding to know if I was taking the piss. I admitted to that sin rather than my own stupidity. Mistakes were painful, and often public, and I was eternally grateful that one did not see print.

At the end of the summer, I was called into City Editor Lou Clancy’s office and told I wasn’t being hired full-time. It was crushing, but Clancy said they’d bring me back as soon as I learned not to rely so much on my writing.

“The only way you’ll become a better writer is if you learn to be a better reporter,” he told me.

It remains the single best piece of advice I’ve ever received in this business.

After a year-and-a-half at the Winnipeg Free Press covering crime and courts (shamefully unaware of residential school history), I was hired back by the Star. More apprenticeships followed – general assignment, city hall, the education beat – before I arrived at what I really wanted to do: to write narrative features about compelling people.

When I left the Star in 1996 to pursue a writing opportunity at the Southam News bureau in Ottawa, a new form of mass media was making headlines. But the internet seemed awkward and smutty.

There was no sense then that the mighty newspaper business would soon be cratered by this digital asteroid.

***

On Sept. 22, 2015, Gerald Tracey was recovering from his bypass surgery when he decided to wander into the Eganville Leader’s offices to catch up with his staff.

“I was still walking pretty slow, but I was feeling a little better,” he remembers.

Tracey wasn’t in the office more than five minutes when he heard an urgent voice on the police scanner dispatch more units to a murder scene in Wilno. The suspect was believed to be headed for the nearby town of Cormac.

Tracey knew instantly that Basil Borutski had snapped: He grabbed his camera and sped towards Cormac.

He had written about Borutski when his Round Lake house burned down under mysterious circumstances in 2011, and again when Borutski posted belligerent signs that warned certain people to stay away from him.

“I never really went near Basil because I kind of knew he was one of these explosive guys,” says Tracey. “So it was always just, ‘Hi Basil,’ that sort of thing.”

Reporting for a community newspaper is an intimate form of journalism. Tracey has often recognized the victims at accident and fire scenes. He has mourned around kitchen tables with their relatives.

The day of Borutski’s rampage was no different. Nathalie Warmerdam was a home-care nurse who had looked after Tracey during his post-operation convalescence. She had also written to the local police services board in defence of Borutski, with whom she once had a relationship. Tracey knew she lived in Cormac.

In Cormac, an OPP cruiser blocked the road that led to Warmerdam’s house so Tracey found a nearby vantage point that gave him a clear view, across a field. He captured pictures of the police escorting Warmerdam’s son out of the bush.

As Tracey later reported, the 20-year-old fled the house and called police when an armed Borutski stormed in and attacked his mother.

Tracey wouldn’t learn the full horror of that day – three local women dead, including Warmerdam – until he was back in Eganville. It was, he says, among the most memorable days of his career.

Tracey has covered many painful stories close to home: the arrest and conviction of his parish priest, Robert Borne, for indecent assault; fires that destroyed Eganville’s Grace Lutheran Church and his own St. James Roman Catholic Church; the scandal that enveloped a close personal friend, the former CEO of Renfrew Victoria Hospital.

“When I think now of some of the things that have happened and that we’ve covered, I can hardly believe it,” he says. “But at the time, you can’t stop and think about it because you have to go on to the next thing, and the next and the next.”

Tracey has knit himself to the community he covers. He has volunteered for a raft of organizations, raised money to assist the victims of tragedy, and chaired committees to rebuild the bell towers at St. James and Grace Lutheran churches.

He has also helped raise millions of dollars to build an Eganville assisted living complex, a splash pad and the town’s Centennial Park, among other things. In May, Centennial Park was renamed in his honour.

“Gerald is truly indefatigable when it comes to supporting his community,” says former Liberal cabinet minister Sean Conway, the longtime MPP for Renfrew—Nipissing—Pembroke.

Conway didn’t always see eye to eye with Tracey, an avowed conservative, but he couldn’t help liking the man.

“One of Gerald’s many good qualities is that people like him,” says Conway. “He’s a true extrovert; he can’t help himself. When he walks into a room, he’s anxious to meet people: ‘Who are you? What are you about? What’s your story?’ He’s a guy with a bottomless pit of curiosity.”

***

Newspaper reporting can be a relentlessly odd, compelling, emotional, and sometimes, traumatic business.

My strangest experiences came in writing about Catholic priests.

After my Ottawa Citizen colleague Meghan Hurley and I exposed Rev. Joseph LeClair’s expensive gambling problem and his unfettered access to cash and proceeds at Blessed Sacrament Parish, the newspaper came under enormous pressure. The clear implication was that LeClair, a hugely popular and charismatic priest, was stealing from his church.

LeClair steadfastly denied any wrongdoing and encouraged his parishioners to cancel their subscriptions. Hundreds did.

At a jammed public meeting, held in the basement of the church just a few blocks from my house, Hurley and I were asked to stand and were enthusiastically jeered by the audience. Speaker after speaker – some of them my neighbours – denounced us and our reporting.

The irony was that many people in that room had to long ignore LeClair’s sins for us to expose them. The few who wanted LeClair stopped turned to the newspaper as a last resort after conventional avenues failed them.

It would take two years for LeClair to admit in court that he stole from the church to feed his gambling addiction.

Years later, it would be another priest who would offer the strangest, most disturbing interview of my newspaper career.

In researching the history of clergy sexual abuse in Ottawa, I came across a lawsuit the diocese had filed against its insurance company: the 2016 suit sought coverage for a series of abuse settlements that had not been made public. One of them involved Rev. Barry McGrory, the former pastor at Ottawa’s Holy Cross Parish.

McGrory was retired and living in Toronto when I called about the secret out-of-court settlements made by the diocese for his conduct in the 1970s and 80s. McGrory denied everything, but when I shared details of the settlements – including the names of the victims I had interviewed – his tone changed.

He tried to rationalize his behaviour, then justify himself. He admitted to sexually abusing both boys and girls, but sought to make himself the victim in our bizarre, hour-long interview.

McGrory told me he was a sex addict plagued by a disorder that made him attracted to adolescents, many of whom, he said, were attracted to him. He complained that the diocese knew about his problems and did nothing.

I asked him how many young people he had abused during his clerical career. McGrory said he had “no idea.” I asked him what it was like to live with his history of abuse. “It’s pretty awful,” he said. “It’s absolutely disgusting, but I believe in a merciful God.”

Three more victims of McGrory’s abuse came forward after the story was published. He was charged criminally, and convicted in two of those cases.

As strange as it can be, the newspaper business offers many gifts, the greatest of which is the opportunity to speak with people who have experienced seismic moments in history.

I was spellbound listening to Ron DiFrancesco describe his escape from the South Tower on 9/11. Hamilton-born, DiFrancesco was the last man out before the South Tower collapsed, and was one of only four people to make it out alive from above the plane’s impact zone on the 81st floor. A devout Roman Catholic and a father of four, DiFrancesco said he heard a voice – he believes it was God – tell him to get off the floor of a smoke-filled stairwell. He ran through the smoke toward a pinpoint of light, emerged beneath the impact zone, and escaped the building as it collapsed. He was still suffering PTSD at the time of our interview, and his voice was barely above a whisper as he recounted his story.

Then there was Ottawa’s David Shentow, a Holocaust survivor who experienced some of the darkest places our universe has ever known: Auschwitz, the Warsaw Ghetto, Dachau. At Auschwitz, he was prisoner 72585, a number tattooed on his left forearm. In our interview, he was brought to tears remembering how he once bartered away a starving man’s bread in return for cigarettes.

There has been much trauma in Ottawa during the last quarter-century: tornadoes, floods, bus crashes. The 2014 Parliament Hill attack. The 2022 truckers’ occupation. The Eastway Tank explosion. The fentanyl epidemic.

As a reporter and writer, I’ve suffered vicariously through all of them.

But the hardest stories to write were about lost children. The yawning chasm of grief they left behind unnerved me, but sometimes it was necessary to bear witness. I have interviewed parents who lost children to suicide, drug overdoses and a moment’s impulsiveness.

Then there was Jonathan Pitre.

***

The Eganville Leader remains a profitable business: the paper pulled in $1.3 million in revenue last year.

It has 3,800 subscribers in a town of 1,200 and regularly sells papers across Renfrew County thanks to its broad-based coverage of the Ottawa Valley. The Leader has continued to thrive even as newspapers disappear from small communities across the country.

A recent report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives said the country has lost about 25 print media outlets a year since 2014. The problem has been most pronounced in small towns, leaving about 2.5 million Canadians with no local news outlet.

Such news gaps, the report said, are usually filled with social media and “often with misinformation.”

To make matters worse, the report warned, “the rate of local news deprivation across Canada is snowballing.”

So what does it mean when even a profitable paper like the Eganville Leader – one of the most successful community papers in the country – can’t survive?

Tracey says there are a few fundamental problems. Institutional advertisers such as Renfrew County, local hospitals and school boards are increasingly relying on the internet and social media to get their messages out. Advertising revenue from the county alone has dropped by more than $20,000 a year, Tracey says.

(When a county or hospital official asks Tracey why he didn’t cover one of their events, he’ll remind them that advertising pays for his reporters: “You might find out down the road,” he’ll preach, “that you need newspapers in this area because people still read them.”)

The internet has also changed the way people consume news. Young readers have little inclination to leaf through a broadsheet newspaper. It means, Tracey says, advertisers targeting a younger audience – car dealerships, for example – are less likely to turn to the Eganville Leader.

“I don’t know what the solution is, but I do think if it continues much longer like this, more papers will close,” Tracey says. “I’m just exiting sooner than many others will.”

The Eganville Leader also faces a unique problem in that Tracey has to replace himself as publisher – something that has proved exquisitely difficult. He is among the last of his kind: a publisher immersed in his community who works seven days a week collecting news, taking photos, selling ads, managing a business.

“You need a person who will commit themselves to it: It is your life. You think, you sleep and you breathe it,” Tracey says. “When you go to bed, you’re always thinking about story ideas and business ideas. I’ve done it so long I don’t know what’s work and what’s pleasure anymore.

“But nobody wants to work like that now.”

***

The day Jonathan Pitre died was the most difficult of my career. In the strange way of newspapers, it was also one of my most memorable.

I first met Jonathan when he was 12 years old. He had freckles, blue eyes, strawberry-blond hair and a sunny disposition that seemed at odds with the reason I was writing about him: his life with Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB), a rare genetic disease that caused his skin to blister, shear and scar. His body was wrapped in gauze to guard against the mildest of friction.

Jonathan loved sports, books and dogs, and was in every way a regular kid except that he lived with one of the most painful conditions known to medicine. I told his mother, Tina Boileau, to call me if there was anything I could ever do for him.

Two years later, she did. Jonathan had become an ambassador for an EB charity, DEBRA Canada, and was raising money. Could I help?

I went out to see Jonathan with Citizen photographer Julie Oliver. His EB had worsened: his wounds were bigger, deeper and slower to heal. Blisters covered much of his body and plagued his mouth and throat.

Still, he was full of positive energy and talked excitedly about meeting other EB patients at a Toronto conference. “Before that, I didn’t really have a meaning in my life,” he told us. “I came to understand that my role in life was to help people with EB.”

I had my story, but Julie wasn’t satisfied with her pictures. She asked Jonathan if she could photograph his bathtime ritual. It was an hours-long ordeal: He soaked in a mixture of water, salt and Javex (to kill bacteria on his skin), then his bandages were unwrapped and his mother lanced new blisters before rewrapping him in fresh gauze.

I was deeply uncomfortable with Julie’s idea, and told Jonathan he didn’t have to show us his body. But he was keen to educate people about EB and readily agreed to be photographed during his bath.

Words could not convey the enormity of Jonathan’s challenge; Julie’s pictures did. They revealed his sprawling, raw wounds while somehow capturing his fragility and bravery.

Those images, published on Nov. 1, 2014, launched Jonathan onto an international stage. The story went viral and he was featured on TSN, ESPN and in People magazine, USA Today, The Daily Mail and many other publications. He raised more than $200,000 for EB research, was made an honorary NHL scout by the Ottawa Senators, circled a racetrack in Montreal with Indy car driver Alex Tagliani, and attended the NHL Awards ceremony in a suit from Sidney Crosby.

I wrote about both his adventures and his escalating health issues.

In September 2016, Julie and I visited Jonathan and his mother in Minnesota, where they had travelled for a stem-cell transplant – the only treatment that might arrest his advancing disease.

His first transplant failed, but a second took root in his bone marrow. Slowly, despite many setbacks, wounds on his legs, feet and back began to heal, and he talked eagerly about the prospect of coming home.

It was one of the reasons I was thunderstruck when Tina called me on the morning of Thursday, April 5, 2018. She was so distraught, I had a hard time at first understanding what she was trying to tell me: Jonathan was dead.

She unfolded the terrible story of his fatal infection, but I was so upset that I didn’t take any notes. I had to call her back to confirm the details.

Tina wanted time to drive back to her family in Canada before I published a story, and she asked me to hold the news until Saturday’s paper. Of course, I agreed.

I told my editors the news, and began writing a feature obituary about Jonathan with the computer screen swimming in front of me. Late that morning, my editors said there was a problem: If we published the story on Saturday, it would be inside a full front-page advertisement. If we published Friday, the story would own the front page.

They wanted me to call Tina to explain our advertising exigencies, and tell her we wanted to publish the story about her son’s death, tomorrow.

There was also concern that the news would leak out over the ensuing day and that we’d lose our exclusive.

It seemed ridiculous.

I made the call.

Tina, the most gracious of people, agreed. Now under deadline, I wrote Jonathan’s obituary in a fog of guilt and grief, but also with a deep sense of responsibility: to do justice to his remarkable life, to his defiant embrace of happiness.

I left the newsroom late that day in a ragged state, but absolutely sure I had done my best. The next morning’s paper filled me with a strange mix of woe, pride and exhaustion, and the worst thing was, I had to go back into the office to write about the public’s reaction to Jonathan’s death.

When I slouched into the newsroom, there was on my desk a gift from my closest newsroom colleagues: a bottle of Writers’ Tears Irish Whiskey.

It was the perfect coda to a fine and terrible newspaper day. I sat down for another.

***

In the lobby of the Eganville Leader’s John Street offices, a steady trickle of customers arrives at the front desk to pay for their subscriptions – and to offer their final respects.

“I sure will miss the paper,” Elaine Reinert, a longtime subscriber, tells receptionist Teresa Plotz.

Reinert, 82, says she and her husband will miss holding a newspaper in their hands. “It’s just something we’ve done all our lives,” she says. “You open it up, and say, “Oh my God, look what happened, look at who died now.’ I think it’s the older class of people that are really going to miss it.”

Bill Behan, 74, a retired civil servant, says he has looked forward to the paper every Wednesday for almost 30 years.

“Every Wednesday, you go down to the post office and there’s your Leader,” he says. “I read their sports and local news, and if there’s something coming up, like a barbecue or something like that, it’s all in there.”

Gerald Tracey understands the angst of his readers. He says he feels “almost ashamed to be letting them down.” He’ll miss the paper, too.

Few people know more about the Ottawa Valley than Tracey. He spent countless hours trolling through thousands of old newspapers to put together a 945-page book to mark the first 100 years of the Eganville Leader. He can remember names and connect family histories like a puzzle master.

“I love talking to people. I’ll miss the people and I’ll miss telling their stories,” he says. “Everybody in life has a story. I don’t care who that person is, right?”

Tracey keeps a file folder with readers’ cards and letters eulogizing the paper. Some lament the loss of the Leader’s secondary uses: wrapping up dog dirt, wiping cow udders, starting campfires. Many mention the paper’s handsome obituary section, which boasts colour photos and generous amounts of white space.

“We’ve had at least three people say they hope they die before you close the paper, because you do such a great job on making the obituaries look so nice,” Tracey marvels.” We’ve had three of those. Can you imagine?”

What will Tracey miss most? The action.

“I know right now I’m going to go nuts,” he says of his post-newspaper life. “I had last weekend at the cottage uninterrupted, and I still made three trips into Eganville from Golden Lake. I’m not one to sit around and do nothing.”

***

The arc of my career has traced the slow decline of newspapers.

I have watched our staff get cut in half and then in half again. That digital asteroid, the internet, obliterated our advertising, cheapened news as a commodity, and obscured the value of truth.

Newspapers have struggled to adjust to that new landscape, but not for lack of effort. They’ve tried delivering news and advertising on a host of platforms – tablets, podcasts, video feeds – all to modest effect. In recent years, much has depended on Google’s inscrutable algorithms, and our ability to optimize stories so that they’ll appear frequently in searches. More recently, the introduction of AI overviews to Google searches altered the ground all over again.

Meanwhile, the pandemic emptied many newsrooms – places where ideas percolated, skills were shared and ambition fired. Today, if reporters and editors work from home, they have to find inspiration through Zoom meetings. It’s not the same (and there’s much less drinking).

And yet, for all it has suffered, this business has endured. And while it is diminished, it is yet full of promise.

Analytics offered by today’s news websites mean reporters no longer have to guess what readers are interested in: the data tells them. (One of the interesting insights from that data is that features – even long features – are valued by readers.)

A new, multi-talented generation of journalists is using that data to explore new ways of telling stories that engage younger, wider audiences.

I’m firmly convinced they’ll succeed. They have grown up in the internet age and understand its rich possibilities for telling and sharing stories. Curated newsletters, for instance, have proven to be a valuable way to share the best and most important newspaper stories of the day.

What’s more, truth and accuracy have started to regain their currency in a world led astray by misinformation and lies. Artificial intelligence could also prove an important force multiplier for newspapers. Carefully deployed, AI can give newsrooms the power to do more — offer better coverage of local debates, government reports, court decisions — with fewer resources.

The future of our business is online, not in print. The newspaper itself is on borrowed time, and the thump of a paper on the doorstep will soon enough join home milk deliveries as a relic of the past.

I’ll miss the physical product – there’s something truly expansive about a broadsheet – but that won’t be the end of the newspaper story.

Whether published in ink or in pixels, stories still matter, and the essence of telling them remains much the same as it was when I was delivering the Hamilton Spectator. Drama, suspense, compelling people – and good reporting – remain part of a durable formula.

I’ll also miss the challenge involved, and in particular, the moment when the reporting is finished and the job of building a story begins. There are so many possibilities to consider.

As for Gerald Tracey, what will he miss the most? That’s easy, he says: the action.

“I know right now I’m going to go nuts,” he says of his post-newspaper life. “I had last weekend at the cottage uninterrupted, and I still made three trips into Eganville from Golden Lake. I’m not one to sit around and do nothing.”

Editor’s note: The Ottawa Citizen is proud to publish journalism that makes a difference, with reporters who pour their hearts and souls into storytelling. We’ve served Ottawa for 180 years, and don’t plan on stopping anytime soon.

If you value the work of journalists like Andrew Duffy — and stories that no one else is telling — visit our homepage: ottawacitizen.com. If you like what you read and want more, we’d love it if you’d sign up for our curated Evening Citizen newsletter (it’s free!), which features notes and commentary from Citizen editors and lands in your inbox every weeknight: ottawacitizen.com/newsletters.

If we’ve earned your trust and you want to help us grow, sign up for a paid digital or print subscription: ottawacitizen.com/subscribe.

Thanks for loving good journalism.

Share this article in your social network