I don’t remember the exact day I took off from LaGuardia Airport, heading to Toronto for 2001’s TIFF. But I do remember arriving at the airport ridiculously early and wandering around the food court when I recognized an older gentleman chowing down. “Excuse me,” I asked, “are you the songwriter Jimmy Webb?” He was, and I expressed my admiration, and I took it as a good omen for the festival.

And for a few days this feeling was validated, though the pleasant late-summer weather amusingly contrasted with the frequent darkness of the movies I watched.

That included David Lynch’s “Mulholland Drive,” which I had seen and reviewed for my magazine Premiere but which I was more than happy to see again. The night of Sept. 9, Premiere hosted a party at Prego della Piazza. Lynch showed up with his stars Naomi Watts and Laura Elena Harring on each arm. Spotting me from across the room, he yelled, “Thanks for the four-star review, Glenn!”

A few minutes later he added, “Great pizza, Glenn!”

I couldn’t really take credit for that. But I did, honest to God, introduce Lynch to actress Monica Belluci, so you can thank me for that cameo in “Twin Peaks: The Return.”

Also at the party was Richard Harris, there promoting his superb “My

Kingdom.” I approached him and told him of my airport encounter with Webb, who had written Harris’s hit single “MacArthur Park.” And this is verbatim how Harris responded: “Jimmy Webb! Ha ha ha ha ha! Jimmy Webb!”

So, on the morning of Sept. 11, I had a real spring in my step as I made my way to a screening of Mira Nair’s “Monsoon Wedding.” The film was itself the kind that sends you, as the critical cliché goes, floating out of the theatre.

Afterward, I was puzzled as I looked out into the lobby and saw a colleague sobbing into her phone. I approached her to see if I could be of any assistance and she said, “They blew up the World Trade Center.” And I said, “What?” We decided to hit the street and see if we could find more news.

We stormed into an electronics store and asked if they could switch a TV to a news channel. We were told, um, no. So, we ran to the Park Hyatt, where many in the industry were staying, and fell into a state of shock with everybody else gathered there.

Then began the futile attempts to get anyone in New York on the phone. I had a good friend who lived in downtown Manhattan, the site of the destruction. Couldn’t scare him up. (I did later; he fled the area in dust and smoke, which led to lung issues that persist to this day.)

I called a woman I had been seeing, from whom I’d become somewhat estranged, and she eventually got back to me with a two-word email: “I’m OK.” I managed to get through to my landlord, who told me my cat was fine, although he was pacing more than usual.

My aunt had seen the second plane hit from her front window in Brooklyn Heights. As this all sank in, my perceptions of the movies I’d seen over the past few days, while hardly front of mind, began to shift.

What my colleagues and I felt all day, and for a while after, was a stomach-churning sense of impotence.

That night, the Park Hyatt bar was filled with film folk who, like the rest of us, could not leave town. No flights. On hearing me order a Scotch in my Yank accent, Ray Winstone, one of the stars of Fred Schepisi’s “Last Orders,” bellowed, “We’re with ya, mate!”

David Hemmings, no longer the sleek sex symbol of “Blow Up,” but still charismatic as hell, did close-up magic tricks for fans. “You wanna know my politics?” he asked me. “Bomb ’em all. Including Northern Ireland.” Yikes! Nevertheless, he was a great drinking companion.

I got more quietly sloshed with filmmaker Claire Denis and critic Meredith Brody, tucked away in a corner, while watching CNN with the sound off.

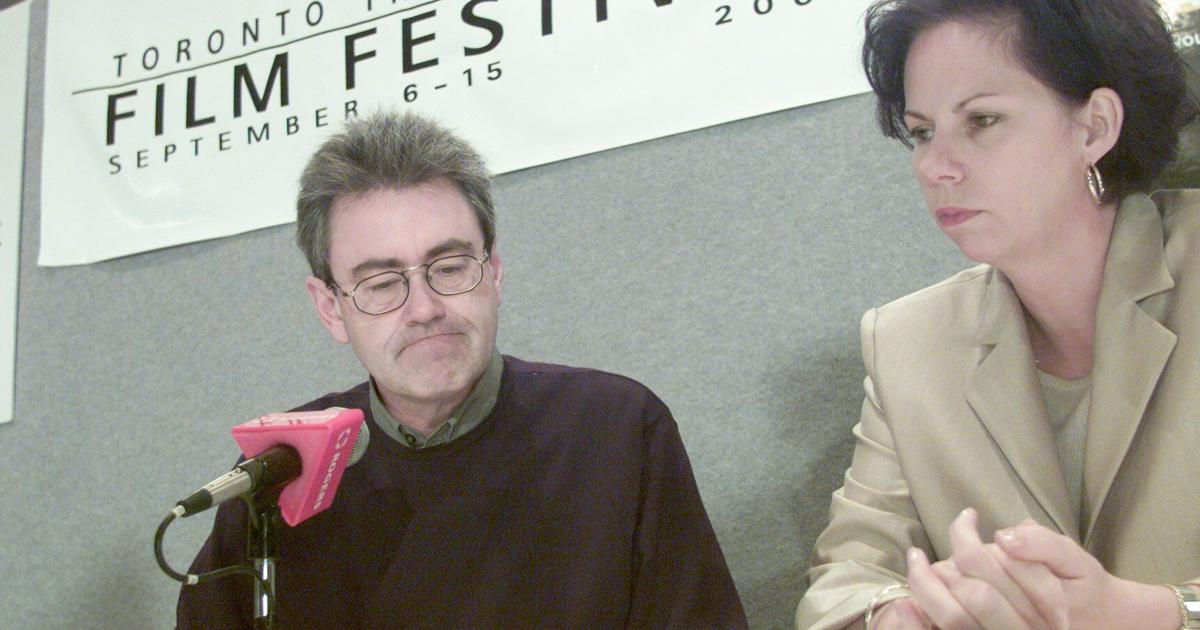

The next evening, Leah McLaren, then a newspaper columnist, took me to an elegant dinner and indulged my shell-shocked blubbering. At sea until the festival determined whether it would continue, I took to the streets. Once TIFF’s Piers Handling announced it would go on, there was some divisiveness. Some attendees thought more time was needed to process. Just what the “processing” would accomplish was never made clear. Those who wanted the shutdown to continue were deemed selfish and parochial by those who wanted to get back to the screening rooms.

I didn’t have much of an opinion, frankly, because I was in a complete abstracted haze. And I wondered how the heck I was going to get home. While I was figuring that out, I took in a few more movies.

Eventually, I opted for a 16-hour train ride. I bought a very thick book.

In the still of a New York City night, I emerged from Penn Station onto eerily quiet streets. I came home to a place that was, in a sense, entirely new. And I carried with me, and still carry with me, a great deal of love and gratitude for Toronto — a place of welcome and comfort that I haven’t been back to in a while, but remains with me, in memories both fond and troubling.